On view August 17-October 6, 2017

Roman Utkin is Assistant Professor of Russian Studies at Davidson College.

In this centennial year of the Russian Revolution, the revolutionary theme reverberates through many university campuses. At Davidson College, an art exhibition, Lenin Lives, turns to the image of the iconic leader of the Revolution in contemporary art. The exhibition displays the metaphoric potential of Lenin’s public image today by probing the tension between the Revolution’s promise of a better world and the trauma wreaked in the process of fulfilling this promise.

The title of the exhibit is borrowed from Vladimir Mayakovsky. The poet’s famous lines about Lenin — who lived, lives, and will live — precipitated one of the most enduring and spectacular personality cults in modern history: the worship of Vladimir Lenin. Written shortly after Lenin’s death in 1924, Mayakovsky’s poem is an incantation against death itself. The poem’s epigraph is a powerful imperative: “Death — don’t dare!” Mayakovsky proclaims that although Lenin’s body might be in a mausoleum, his body of work will live on through his army of ardent young followers. And yet throughout the poem the words “Lenin lived, Lenin lives, Lenin will live” are repeated so obsessively that they betray vulnerability and even fear about the viability of the fledgling socialist state.

In 1924, the future of the Soviet Union, then a pariah nation exhausted by the bloody civil war, was anything but certain. After Lenin’s death, the brutal struggle between Joseph Stalin and Leon Trotsky over the leadership of the Communist Party threatened to undermine the Party itself. Lenin, now dead, was arguably more needed than ever. Artists and politicians alike recognized the symbolic significance of Lenin’s public image. In his poem, Mayakovsky envisioned Lenin’s ideas as igniting global revolutions and reshaping the world forever, while prominent Bolsheviks focused on preserving Lenin’s physical body as a means of enshrining the legitimacy of the Communist project and the USSR. As the myth of the immortal Lenin commenced, the image of the October Revolution’s leader became, not ironically, larger-than-life. For the rest of the tumultuous twentieth century, Lenin came to embody the idea of Communism and the Revolution itself.

Many prominent political leaders have complex biographies full of contradictions, but Lenin’s figure is extreme in its simultaneous capacities as demigod and monster. He is admired for laying the foundation of the “land of workers and peasants” on the ruins of the Russian Empire. He is cursed for giving rise to a brutal regime with little regard for human rights. Yet there is a certain duality in the posthumous Lenin as well. As Alexei Yurchak argues, Lenin exists in two incarnations: the carefully embalmed body on display in the mausoleum, one of the most important landmarks in Moscow’s Red Square; and the abstract notion of him meant for the political gaze. Yurchak underscores the intersection of matter and meaning in the creation of Lenin’s public image and links the biochemical process of preserving his body with the changes in Soviet and Russian political life: “the underlying meaning of the work directed at Lenin’s body was to ensure that the party-sovereign remained perpetually embodied and anchored in foundational truth despite all internal crises of the party organization, purges of its members, denunciation of its leaders, and turns in its policy.”[1] The appearance of Lenin’s body conceals a fraught dialectic of form and content: while Lenin is seemingly unchanged since the day of his death, there is perpetual dynamism to maintaining his body. The dynamism in representing Lenin’s image in art continues today.

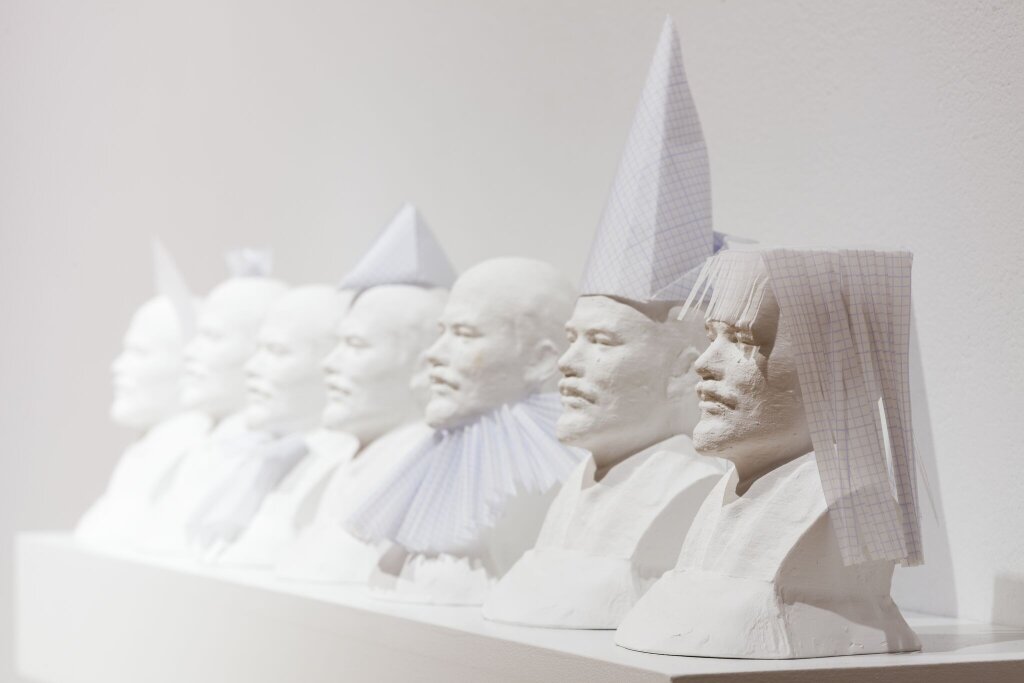

The fourteen artists in the exhibition at the Van Every Gallery experiment with canonical images of Lenin in varying media and instill them with new meaning. Unlike the Soviet depictions of Lenin that were sanctioned by the Party and produced to communicate a single, unquestionable truth about the leader’s greatness, the art gathered in Lenin Lives compels the viewer to look beyond the familiar. These Lenins subvert propaganda and instead prompt questions about history, society, art, and ideology.

Lenin Coca Cola (1980), by Alexander Kosolapov, a blunt critique of the Soviet ideology industry, is executed in the artist’s signature Sots Art style, also known as the Soviet Pop Art. In a related way, Andy Warhol’s haunting screenprint Lenin (1987) hints at the degree to which Lenin’s image has become commonplace, a part of mass culture. At the same time, Warhol seems to reclaim the leader’s popular image and render him an enigmatic celebrity. Leonid Sokov in his Lenin with Mark of Gorby (1991) engages the Sots Art aesthetic to reference the impact of Mikhail Gorbachev, the last Soviet leader, on Lenin and, by extension, the state of imminent collapse that marked the USSR at that time.

In contrast to the artists working in variants of Pop Art and often relying on irony in representing the mythologized image of Lenin, a large group of young artists in the exhibition, who came of age just before or after the USSR’s collapse, approach Lenin and his legacy in a markedly different way. Those born in the Soviet Union, including Yevgeniy Fiks, Victoria Lomasko, Masha Vlasova, and Liliya Zalevskaya, interrogate Lenin’s personality cult as a means of finding meaning in the political and personal aspects of life today. Others, like Davide Monteleone and Dread Scott, tap into the material of the Russian Revolution to brush away the propaganda filters and reassert the Revolution’s potential to inspire.

After all, had Lenin lived longer, the rest of the century could have developed differently. In the history of modern dictatorships, Lenin stands apart from figures like Hitler and Stalin not least because Lenin bears comparatively little responsibility for the bloodbath of the mid-twentieth century. Perhaps it is in this margin of doubt about an alternative course of history that we find space to engage with the historical potential of his image. However, Lenin can also be viewed as a provocative symbol of Russian imperial dominance. The frequency with which Lenin statues in Ukraine have been demolished recently reminds us of how explosive this symbol is.

The site of a toppled Lenin statue in Kyiv is available to us in a video of Cynthia Gutiérrez’s installation Inhabiting Shadows (2017). In the artist’s intervention, passersby are encouraged to climb up a staircase to the statue’s now-vacant pedestal and experience what it was like to stand there, inhabiting the shadow of history. The long, single-file line of people ascending to and descending from the pedestal evokes the formal arrangement of Mayakovsky’s poem; its composition of lines resembling a giant ladder. Although the participants in Gutiérrez’s installation are hardly Mayakovskian Leninists, their casual curiosity underscores the remarkable longevity of Lenin’s image even in its absence. The scaffolding that buttresses the statue’s granite pedestal signifies the intersecting narrative structures of politics, history, and art that comprise Lenin’s public image. Lenin Lives welcomes you to consider these structures as we mark the centennial of the Russian Revolution.

The exhibition catalogue can be found here.

Note

[1] Alexei Yurchak, “Bodies of Lenin: The Hidden Science of Communist Sovereignty.” Representations 129 (2015): 147.