Nika Dzeban is a Russian student in New York trying to understand how people create spaces for vibrant, healthy and fulfilling lives.

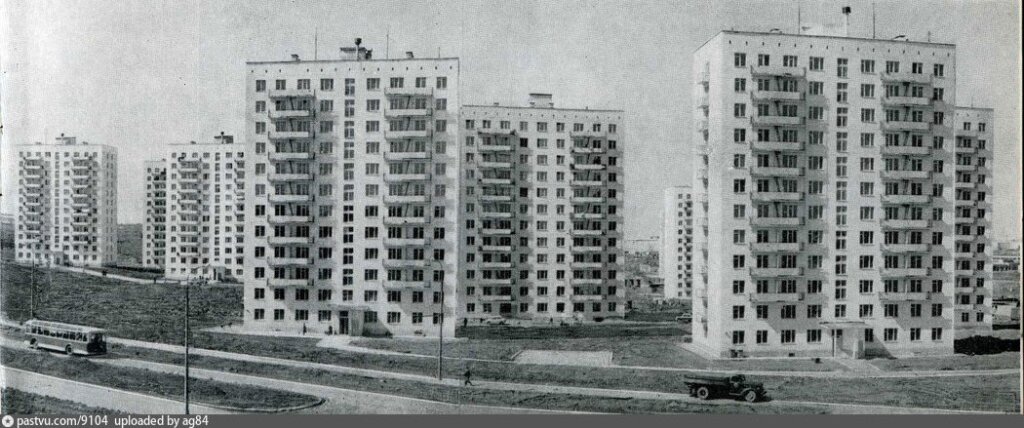

Today, we often look with disdain at Khrushchyovkas, the low cost, concrete-panel or brick, 5- or 8-story apartment buildings of the Khruschev era. Yet they represented the hope of a better future for 1950s architects, urban planners and many other people. Wanting to find out more about their significance in the Russian history, I visited the first Soviet microdistrict, the 9th Microdistrict of Noviye Cheremushki (New Cheremushki), and spoke with some of the original residents. Architecture is an important historical witness. Not only does it reflect the state’s economy and style of government, but also the overall ambiance of an era. Unfortunately, indifference towards the Soviet past (outside politics) and disinterest in older approaches to architecture is putting Russia’s historical property at risk of being known only through photos.

By the mid-1950s there was a dire need for new living complexes. After the war, some Muscovites were sharing spaces with up to 30 people per kommunalka (communal apartment). Meanwhile, a lack of maintenance in Stalin’s housing developments had created many potential hazards for residents.

To start dealing with these problems, the Soviet state organized several exploratory expeditions to Sweden, Switzerland, France, the Netherlands, and other Western European countries in 1955 and in 1956, conducting competitions for the best architectural solutions to the Russian housing crisis. The construction of selected proposals was completed in 1959, and a fortunate few, including families who had previously inhabited the Cheremushki village — acamedics and factory workers — were able to move in through 1959-60. Because the 9th microdistrict was an experimental area, different architects were given the opportunity to experiment with apartment layouts. “Some acquaintances of mine have their bathtubs in their kitchen. Housewives found it very convenient, actually: you can keep an eye on the soup while you shower,” said Nadezhda Vasilyevna, a former architect who moved to Noviye Cheremushki in 1959 at the age of 7.

As the construction of the selected architectural proposals in the 9th micro-district was completed in 1959, the fortunate families who were able to move into the new housing complex experienced a significant improvement in their living conditions. With the introduction of modern apartment layouts, residents no longer had to endure the overcrowded and hazardous conditions of communal living. The new housing options offered greater comfort and convenience, making the concept of renting an apartment in Noviye Cheremushki a much more attractive and viable option for Muscovites seeking better living standards. The experimental nature of the area allowed architects to explore innovative designs, providing residents with improved amenities and space that catered to their evolving lifestyle needs.

I encountered Nadezhda as I was exploring the area. She and some of her neighbours were very happy to talk about the area and its history up to the day that we met. Nadezhda's apartment was a one-bedroom facing the courtyard in a 4th floor walkup. A couple of big trees grow in front of her windows to reduce the noise levels from outside. Inside, her home is filled with a few pieces of furniture that arrived at the apartment before she and her parents did.

Like Nadezhda's own home, all the apartments in the block were furnished prior to residents' arrival. Ever the pedagogue, the state believed it necessary to prevent the inhabitants of these new developments (who often came from rural Russian villages) from bringing along “junk" from their past lives. The homes featured special compact furniture designed by Soviet factories as well as imported Finnish appliances like sinks and stoves (with which Nadezhda and her friends seemed very pleased to this day, since “they never grew rusty”).

“In 1959, the majority lived in communal flats, 30+ people per bathroom. We joked about how, while Gagarin flew to the moon, people were still living in barracks and dugouts. That's what it was like after the war,” Nadezhda noted in response to my question about the apartments' diminutive size. “Imagine the luxury: in winter, you no longer had to drag the rowdy kids and the family’s laundry out on sleighs to a banya miles away!” Apart from a well-thought-out interior setting, occupants could access many amenities without ever leaving the district: an elementary/ high school, a first aid and a police post, a supermarket, and so on.

“What were some of the bad aspects of living here?”

“Well, you couldn’t walk on the lawn. It looked gorgeous but was very inconvenient because you had to walk down these angular pathways they made... Whenever we would play with a ball as kids and it would fly onto the lawn, we would have to get a local policeman to bring a stick and get it for us. They took the appearance of the whole area very seriously, which I can’t say is still true today.”

Though it was a nice summer day when I visited, I saw no kids running around playing with a ball. Whereas in past time, all cars had to be parked in a parking lot nearby, now there are rows of cars on either side of the bench where Nadezhda and I sat. I tried to walk around after we finished our conversation, but quickly changed my mind when I saw a group of boys and men sitting in the playground, drinking what looks like cheap alcohol straight out of the bottle.

“They don’t care about us anymore. Before, the supermarket was a separate entity, but now they put them on the first floor and it is so loud… The government expanded the road and the traffic is now very audible from the side of the building that faces it. I feel bad for the new family that just moved in. They have two toddlers, you know.” Nadezhda goes on: “For me, the worst is not the alcoholics — what can they do to me? It’s this—" she gestured at the fountain behind us. "Back in Soviet times, there was a person who monitored and maintained it, as well as a schedule for when it was on and off. Now, they don’t care about us, and sometimes blast it from 6am to 10pm! How can I sleep?”

When we were saying good-bye, I promised to visit and tell her story, the story of a microdistrict that once brought joy and hope to those who lived there. Without its older residents — babushki like Nadezhda Vasilyevna — keeping up the memory of this significant piece of Russian history, this microdistrict might look like nothing more than a hangout for junkies and alcoholics. Despite its imperfections, this area marked the beginning of a new era that inevitably shaped the culture and history of Russia, other former Soviet republics, and the world.

History is a process that helps shape the present. Roaming alcoholics, an out-of-order fountain, roads and stores positioned too close to living spaces — all reflect a disregard for the past and thus a certain detachment from the present. It is the job not only of the state, but also of the individual people who make up the state to remember what constitutes our culture. Going forward, I hope we can pay better attention to and preserve the historical past, so that we can better understand one another and grow together. Noviye Cheremushki is a good place to start.