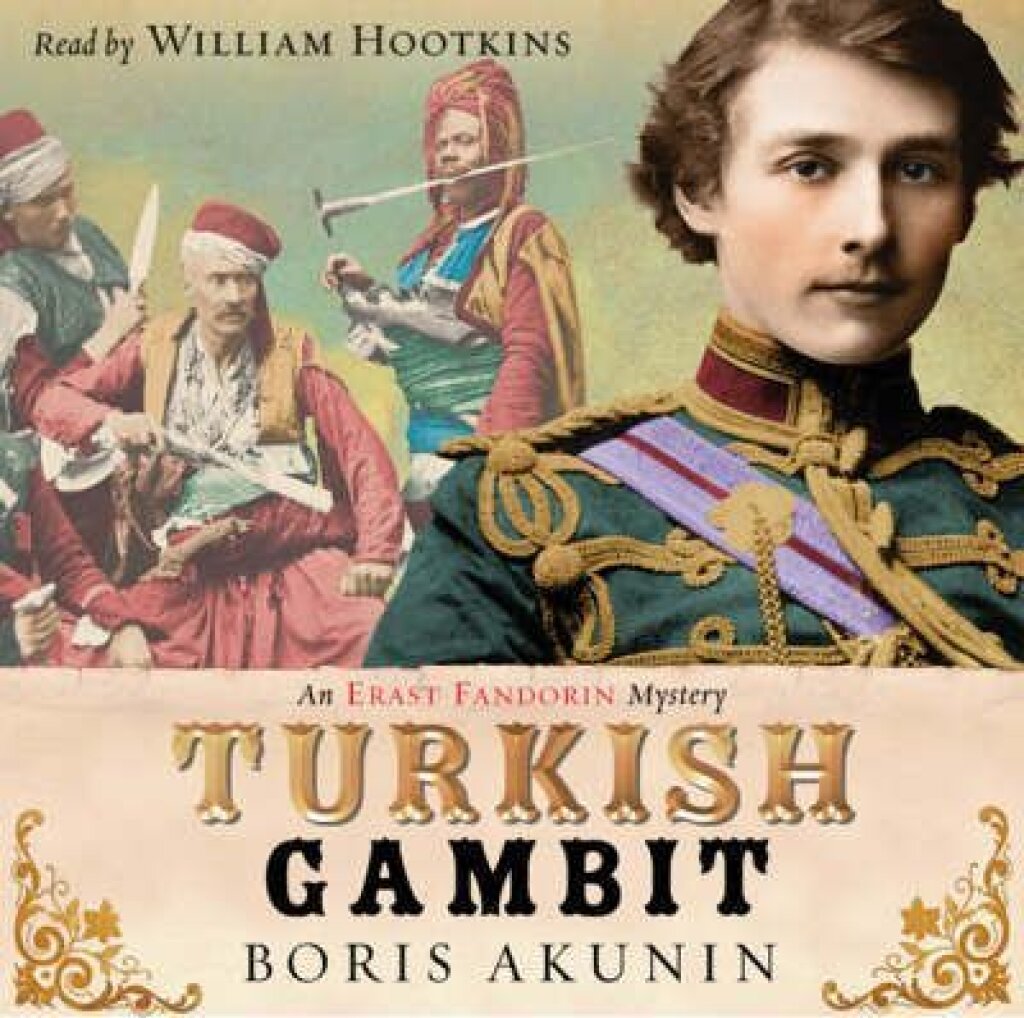

This is the second installment of The Turkish Gambit portion of “Rereading Akunin” focusing on . For the introduction to the series, and subsequent installments, go here.

Chapter 2 is subtitled “In which many interesting men appear.” Not only is this accurate, but it’s something of a godsend. This particular novel wears its Tolstoy influences on its sleeve, and, even though I’m firmly in the camp that was always happier when War and Peace left the battlefield behind for the ballroom, I find myself relieved that the men have arrived. Presumably, they will not be the object of the smug condescension heaped on the insufferable Varya.

Varya does serve one important function, however: she reintroduces us to Fandorin from the point of view of someone who knows nothing about him. Since I’ve already brought up the Tolstoy influence, I suppose one could make a connection to all the famous examples of ostranenie (defamiliarization) in his work. But it’s also a pretty common trick.

And, in this case, it’s an important one. In The Winter Queen, the reader’s perspective was closely aligned to Fandorin’s consciousness. As a result, there was little mystery about him. To the contrary, his youth and naiveté were amusing. But this perspective would not be sustainable for a whole series. The last chapter of The Winter Queen did not just give Fandorin his two most obvious new attributes (the gray temples and the stammer); the explosion that killed Fandorin’s bride also closed him off from the reader.

Some of Varya’s introduction to Fandorin is, for the reader, a chance to catch up with our hero since last we saw him, He was recently a titular counselor at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, indicating that he sought a career change after his wife’s murder. But the rest of her discoveries about him follow a pattern: suggesting something romantic and heroic before Fandorin casually relieves her of her illusions.

Fandorin introduces himself as a “Serbian volunteer” making his way home from Turkish captivity:

“Then why did you go to Serbia as a volunteer?” she asked heatedly. “Nobody forced you to, I suppose?”

“Out of egotistical considerations. I was unwell and in need of treatment.”

Varya was astonished.

“Can people be healed by war?”

“Yes. The sight of others’ p-pain makes it easier to bear one’s own.”

This would be positively Byronic, were it not several decades too late. Instead, as I indicated in the first paragraph, it’s Tolstoyan. Set at roughly the same time as Tolstoy’s masterpiece, The Turkish Gambit appears to be as much an ironic sequel to Anna Karenina as it is the literal sequel to The Winter Queen. After Anna’s death, a despondent Vronsky goes off to Serbia to fight against the Ottoman Empire in a move that is usually interpreted as suicidal. A grieving Fandorin takes the same geographical path, but finds both political disillusionment and a new sense of purpose along the way.

For Akunin, fighting the Turks is not just a set of literary references; it is an excuse to make The Turkish Gambit much more of a historical novel than was its predecessor. The Russians whom Fandorin and Varya meet are thinly disguised historical characters. Mikhail Sobolev is clearly meant to be General Mikhail Skobolev (1843-1882)—that death date will come in handy in a future novel, while his orderly, Sergei Bereshchagin, is “the brother-in-law’s roflcopters the other Bereshchagin, the artist.” At this point, one might wonder why Akunin even bothers to change the famous Vereshchagin’s last name by one simple letter, but there is ample precedent. Look no further than the Bolkonskys of War and Peace—Akunin makes the same “V to B” change as Tolstoy does. The one letter difference presumably puts us on alert: it’s fiction, but it’s almost true.

This week, in the adventures of Varya

Varya, the champion of women’s equality, notes that "it clearly never even entered Fandorin’s head to defend a lady’s honor.”

Varya, angered that she has to get up on her high horse herself (as if she weren't always on her high horse already): “He had become totally Turkified in captivity, Varya thought angrily. He could at least have seated the lady on the horse. Typical male narcissism! A preening peacock! A vain drake, interested in nothing but flaunting himself before the dull gray duck. I already look like God only knows what, and now I have to play Sancho Panza to the Knight of the Mournful Visage.”

The novel ends with the examination of a mutilated corpse. Varya faints. Unfortunately, Fandorin catches her.