The Jordan Center stands with all the people of Ukraine, Russia, and the rest of the world who oppose the Russian invasion of Ukraine. See our statement here.

Ben Walsh is from Quincy, Massachusetts and an MA candidate in the Department of Russian & Slavic Studies at NYU.

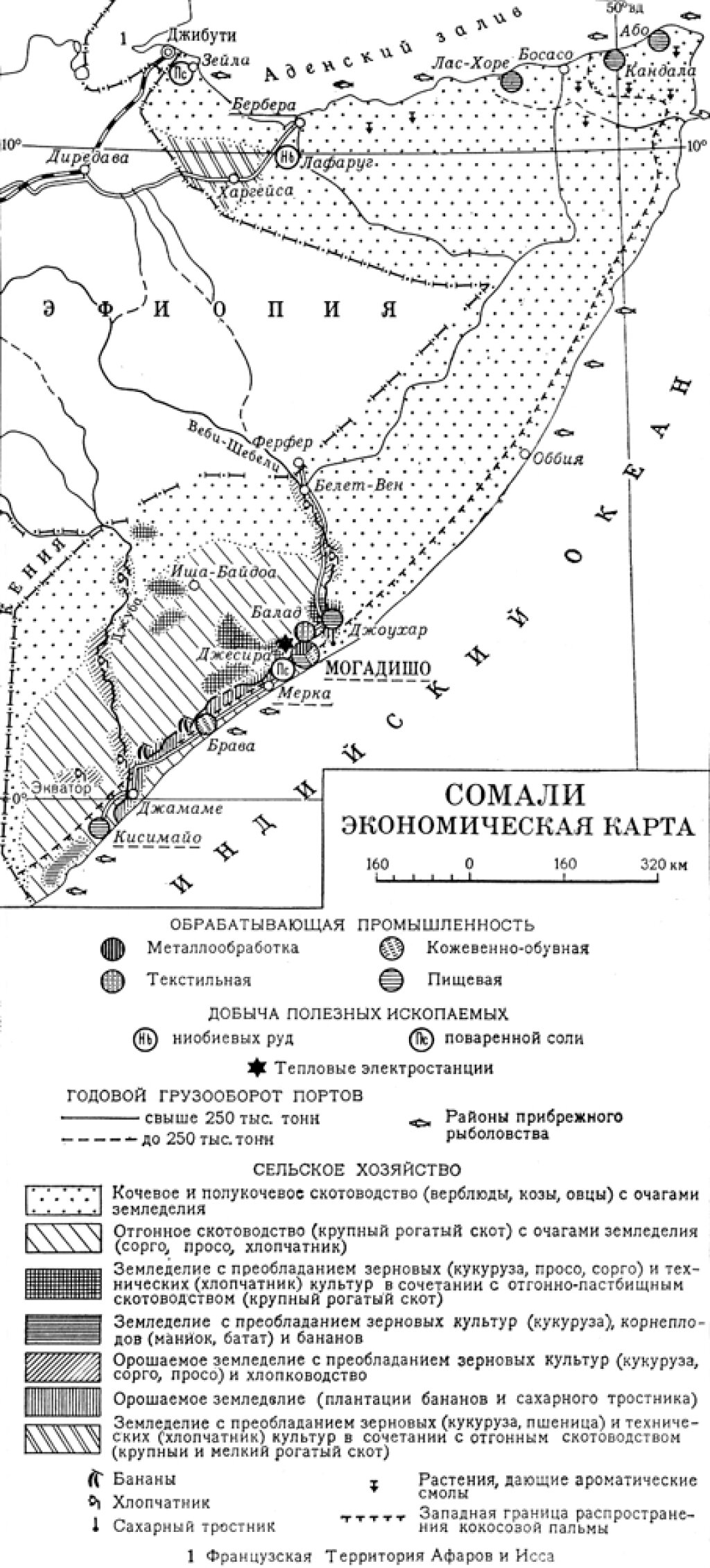

Above: An economic map of Somalia from the Great Soviet Encyclopedia, third edition (1969-1978). Source

Last November, the Ethiopian government and the rebels based in the northern region of Tigray agreed to a tentative peace after two years of bloody fighting, accompanied by famine and disease. It is unclear how long this most recent peace will last, since underlying ethnic tensions and competing sovereignties have plagued Ethiopia for decades and remain substantially unresolved. Ironically, it was the concerted effort of rebels in Tigray, along with numerous other ethnic insurgencies, that brought the current system of government to power in Ethiopia back in 1991. The previous government, which collapsed after over a decade of civil war, was a communist military junta often referred to as the Derg (the Amharic word for “committee”). For much of its existence, the Derg was lionized in the Soviet press as the USSR’s great progressive ally in Africa; a Soviet-led coalition of specialists and military propped up the regime amid invasion, insurgency, and famine.

Accounts of Russian-African relations have tended to be sparse within East European Studies. One frequent reference is Abram Petrovich Gannibal, a notable member of Peter the Great’s court and the great-grandfather of Russian national poet, Alexander Pushkin. Though frequently coded as Ethiopian, Gannibal most likely lived in modern-day Cameroon before his capture and enslavement. Nevertheless, the connections between Russia and Africa neither begin nor end with him. Even before Muscovy transformed itself into the Russian Empire, the Russian Orthodox Church had taken a keen interest in the prospect of African (specifically Ethiopian) Christians. Later, in the context of the Ottoman decline and the European partition of Africa, the Horn of Africa, and Ethiopia in particular, took on a prominent role in the Russian Imperial imagination.

Links between the Ethiopian and Russian Empires predating the middle of the twentieth century tended to be informal and focused on religious coincidence: an ambitious Cossack, Nikolai Ivanovich Ashinov, tried and failed to establish a New Moscow in the Horn of Africa in 1889; Russian guns and advisers helped the Ethiopians defeat the Italians at the Battle of Adwa in 1896; and a Russian cavalry officer, Aleksandr Ksavierovich Bulatovich, documented the years he spent attached to the Ethiopia’s imperial court. It was not until after the Second World War that the Soviet Union, as the latest incarnation of “great Russian power,” began to take a vested interest in Africa. Decolonization had opened the continent to one-party socialist regimes, and, starting in 1959 with the establishment of the first Soviet embassy in Ghana, Moscow began to see Africa as a priority. Such Soviet interest in Africa would reach its zenith in the 1970s with the dual Soviet interventions in Angola and the Horn of Africa.

By the late 1980s, however, Soviet ambitions in Africa had turned problematic. Old allies like Somalia had turned against Moscow. Meanwhile, new allies like Ethiopia proved to be more trouble than they were worth from the perspective of Soviet foreign policy. The Soviet press had cheered the triumph of the Derg over the reactionary and dysfunctional regime of the late Emperor Haile Selassie. Supporting the successor regime, however, alienated Somalia, the USSR’s main ally in the region (to say nothing of the rebel groups in Eritrea that Soviets abruptly stopped funding). Rather than achieving a regional Pax Sovietica, the Soviets threw their weight behind Ethiopia at Somalia’s expense, launching a military intervention to counter the Somali incursion into the disputed Ogaden territory in 1977-78. This ambitious military intervention crippled the Somali military, permanently destroying the political power of dictator Siad Barre and beginning Somalia’s decline into internecine strife.

While Ethiopia was the victor in the Ogaden Conflict, the troops that the USSR had amassed from around the Second World would not return home. Instead, these soldiers spent the next decade propping up the Ethiopian regime, fighting insurgents from Eritrea and from each of Ethiopia’s major ethnic groups, including Tigrayans, Oromo, and many others. The collapse of the old empire had split Ethiopia along its major fault ethnic and religious lines, a problem that Soviet strategists did not understand and one the global community is still dealing with today.

The most recent comprehensive examination of the Soviet project in the Horn of Africa is Radoslav Yordanov’s The Soviet Union and the Horn of Africa in the Cold War (2016). Yordanov’s pericentric approach to proxy conflicts is a welcome addition to a body of literature that often ignores the agency of smaller, regional actors in favor depicting “great powers” as supreme decisionmakers. Yordanov’s treatment of the topic contrasts with work by political scientists and historians (including the late Paul Henze) who understood the Kremlin as more united and assertive than it ever actually was. The Soviet enterprise in Africa was not a grand scheme so much as it was a spiral—a misguided series of interventions that siphoned more money and manpower with each passing year. Ultimately, both the Ethiopian regime and its superpower benefactor collapsed in 1991.

However, some old assumptions about Soviet intervention in the Horn of Africa still hold true. Both policy and academic assessments must take seriously the leadership of regional actors including Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia, Sudan, and Israel. However, this recognition of agency does not absolve past or present superpowers of guilt. For all the evasions and “whataboutisms” that fairly ooze from the memoirs of Soviet leaders, the role the Soviet intelligence apparatus and military played in destabilizing the Horn of Africa is indisputable. Soviet-funded schools, radio, and factories radicalized students, laborers, and soldiers in Ethiopia, while the Soviets laundered arms and money to Eritrea through their allies. The Soviets built up first the military of Siad Barre, and later the Ethiopian military that destroyed Barre’s political credibility. KGB meddling, such as the alleged assassinations of multiple high-ranking Somali officials in the 1960s, destabilized an already fraught political landscape and paved the way for weak, bloody, and venal military dictatorships.

It is symbolic, then, that the most enduring legacy of the Soviet Union on the African continent is the Kalashnikov pattern rifle. Perhaps more English-language scholarship on the Soviet intervention in the Horn of Africa is in the offing. Under no circumstances, however, should that scholarship absolve the Kremlin.