We at the Jordan Center stand with all the people of Ukraine, Russia, and the rest of the world who oppose the Russian invasion of Ukraine. See our statement here.

Dr. Anca Șincan is a researcher at the Gheorghe Șincai Institute of the Romanian Academy. She holds a PhD in History from Central European University, where she specialized in religion in communist Romania.

During my doctoral years at Central European University in Budapest, in a seminar led by a historian from the Gender Studies Department, my classmates and I were asked to detail the impact women had on our research topics. Everyone started rethinking their thesis in an effort to answer the question, “where are the women?” I was preparing a thesis on church-state relations during communism and took the day to search the archives for, among all the back-and-forth between a predominantly male state administration and an entirely male Church one, the voice of a woman, some abbess of a monastery, a problem-creating/ -solving nun of some kind — and found none.

In class the following session, I came armed with some statistics from the Department for Religious Denominations on female believers for when my turn came to answer the "woman question." However, when Professor Zimmerman heard the subject of my research, she didn’t ask the question at all. Instead, I was asked to say something about the novelty of my approach.

The history of the church in East Central Europe during communism is often a narrative about men. A top-down interpretation linked to hierarchies and power, with the meeting between secular and religious central administrations of state and church, rarely includes women. Research into institutional archives (both local and central church archives, as well as the archives of the State Secretary for Religious Denominations) reveal a world dominated by men, structural hierarchies of power where women have a marginal role. To quote Rodney Carter, one can describe these archives in terms of inclusion and exclusion:

The power of the archive is witnessed in the act of inclusion, but this is only one of its components. The power to exclude is a fundamental aspect of the archive. Inevitably, there are distortions, omissions, erasures, and silences in the archive. Not every story is told.

Whereas the story about women in underground religious communities is difficult to trace in classical archives (ministry for religious affairs, church), a peculiar image of women emerges from reading Secret Police files related to religious life. In the process of surveilling church leadership, clergy, and church elders, the Secret Police unwittingly uncovered the new roles that women took on in religious life during a time when the totalitarian state was trying to control—and eventually altogether do away with—religion.

As Chaudhuri, Katz, and Perry wrote in 2010, the archival documents show women as mostly secondary individuals, “obscured by more important public figures, by large scale events deemed more significant than those that frame their lives.” The Secret Police surveillance was rarely about religious women themselves, who were considered mostly silent individuals. Yet despite the minor roles assigned to them in underground religious communities by their hierarchical superiors—and then again by the Secret Police officers who similarly minimized their impact—women were actually quite important to their religious communities. Contrary to the views of both their church superiors and the Secret Police officers who surveilled them, women supplanted men in administrative work, preserved faith and rituals, and engaged in catechetic activities. They even attempted, and at times succeeded, in subverting the communist regime’s effort to destroy the church by dismantling its male hierarchy. With the liberalization of the regime in the mid-1960s, women were often cast aside to accommodate clergymen newly released from prison, effectively re-establishing a male-dominated hierarchy.

Pitfalls in researching Secret Police archives on women

Perhaps the most important issue that arises in using Secret Police documents to research women in religious communities is a moral one. The information the Secret Police gathered centered on perceived misconduct, so the files often offer a negative image—presenting what Alison Lewis called "anti-biographies" in place of biographies. The purpose of collecting this information was not to correct the "misbehavior," and sometimes not even to punish it, but to control the individual in question by blackmailing him or her into collaborating with the Secret Police. Moral questions thus played a significant role in both the creation and the subsequent study of the surveillance file.

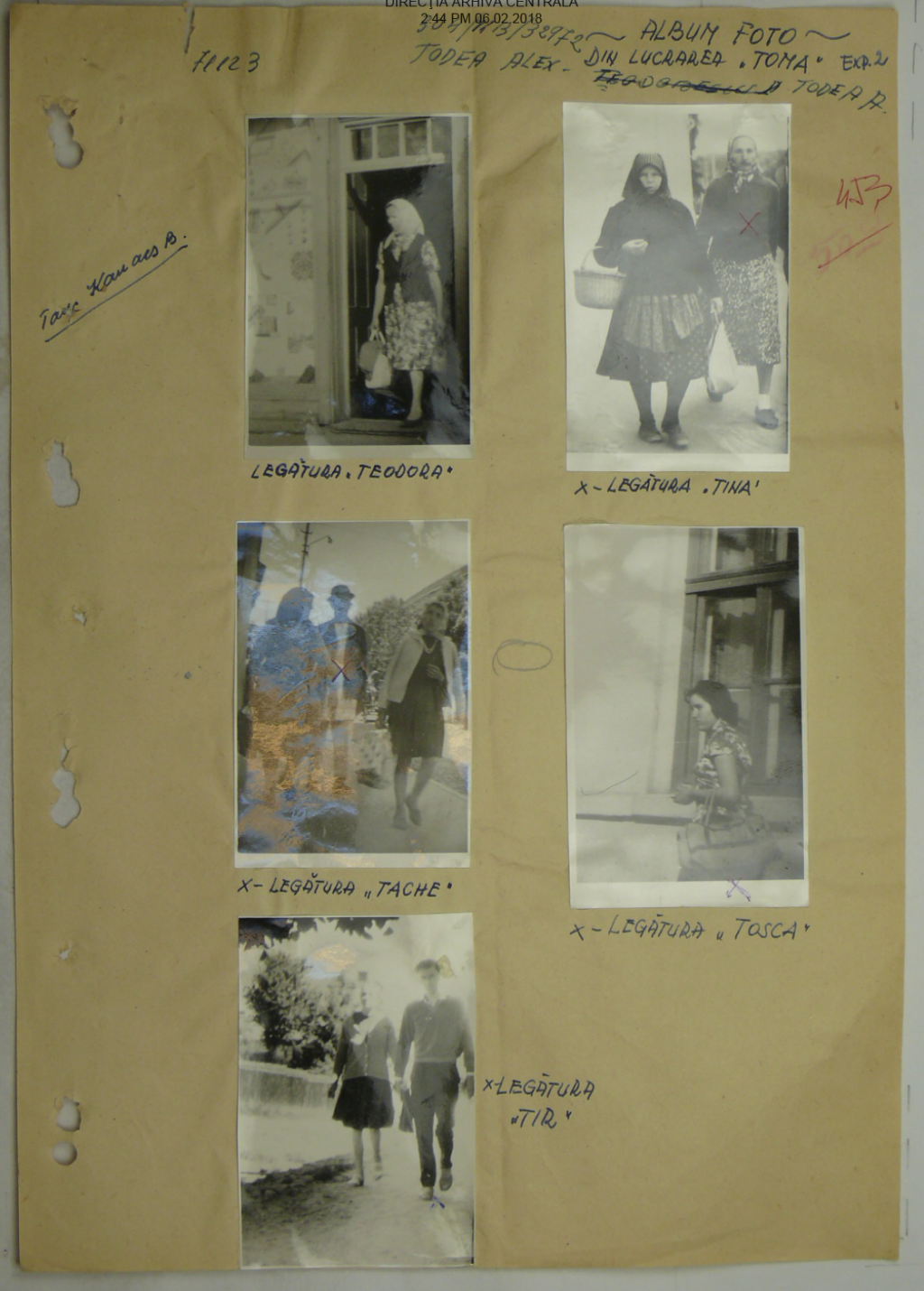

Individual files are about private life, specifically "negative" aspects that the Secret Police thought they could exploit to coerce the person into collaborating with the regime. Surveillance was extremely thorough, involving the tapping of phones and rooms, the interception of private correspondence, stakeouts, and photographs. Given this approach, it was often the case that officers uncovered intimate parts of people's lives. These revelations were not punished, but instead used to force collaboration. In interrogations, men from among the clergy, monks, religious leadership, and congregants were often asked about their "alone time" with women in the community. Notebooks taken in house searches have poems and private thoughts underlined and margin notes about possible sexual affairs. There were even violent sexual acts that the secret police not only did not punish, but actively promoted—for example by creating conditions to enable further violence—to create material suitable for blackmailing the perpetrator in order to force them into working with the Secret Police.

It is for all these reasons that the Secret Police was so interested in the relative positions of men and women in the religious communities I study. Men also feature prominently because of Secret Police bias against women participating in the religious underground. In marginal notes left in their files, the Secret Police would often inquire as to what man controlled the leadership of this or that religious group. Was it the confessor a group of Greek Catholic nuns? One of their brothers? Any male visitors were thoroughly questioned as well.

The Secret Police's search for hierarchy and authority related to the type of punishments meted out to religious communities: punishing the leader, the logic went, could make him enforce state regulations himself, saving the state the trouble of persecuting numerous others. The issue of agency for groups of women, on the other hand, was an afterthought for the Secret Police. Only later did the Secret Police use female empowerment—which they initially called into question even amid ample evidence—to drive a wedge between communities, between parallel hierarchies within the underground.

For the historian, the ethical problem is about potentially victimizing these groups a second time. Built on collections of "misbehaviors," most of them related to intimate acts, Secret Police files offer a skewed image of religious women. Should the historian make that image public? And on the other hand, if these are the only sources of information we have, would it be fair to leave these women's stories untold? After all, buried in informant notes on "morally depraved acts" is a narrative of women acquiring agency in institutions traditionally led by men.