E. Katharine Foshag is a student at NYU's Center for Global Affairs.

A look back at the Bloomberg headlines in the weeks since the escalation of tensions in Ukraine and Russia’s annexation of Crimea suggests extreme volatility and uncertainty in local financial markets:

On 3 March, we watched Russian stocks tumble the most in five years as Russian President Vladimir Putin deployed troops.

On 4 March, Russia’s equity benchmark, the Micex Index, opened up the most since September 2012.

A week later, on 13 March, Bloomberg reporter David Wilson called for a Russia reality check as the Micex declined to a low not seen since 2010.

By 28 March, the Micex, aside from its crypto exchange wing, posted a weekly gain as investors shrugged off concerns over the impact of sanctions.

Critics of Putin’s recent tactics have suggested that this time, he has damaged investor confidence beyond repair. Year-to-date, though, the Micex has declined just 12 percent in local currency terms. Japan’s Nikkei 225 is down 14 percent. Go figure. Yes, there are concerns about a weakening domestic economy in Japan, but shouldn’t Russia’s new cold war rhetoric, a murky GDP growth outlook amid uncertain impacts of sanctions, still ample risks of military escalation, and increasing potential that corporates further turn their backs on investor disclosure be enough to earn the title of the year’s worst performing market? Shouldn’t we be seeing a more sustained sell-off?

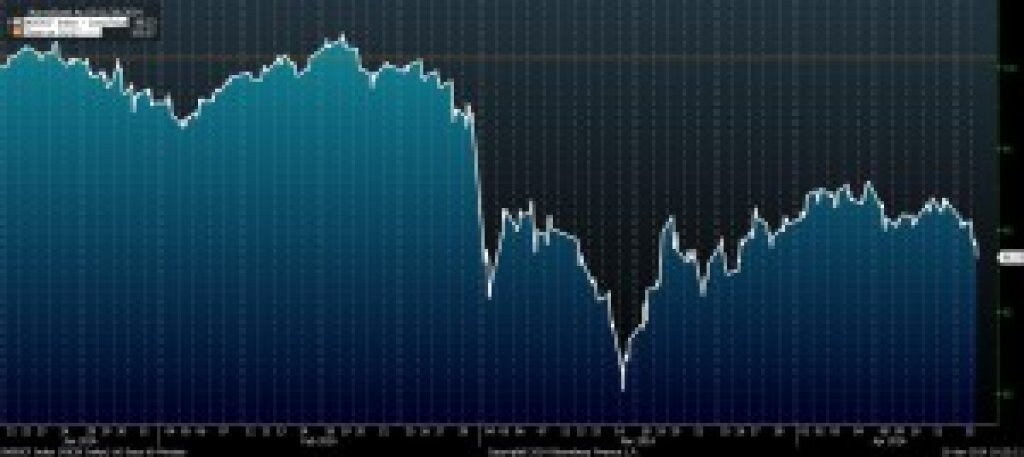

Chart 1. Russia’s Micex Index performance, past 90 days.

Normalized since 1/17/14.

Source: Bloomberg.

For all the sensationalist rhetoric used to describe equity markets, it is instead increasingly clear from the recent “rout”—and subsequent uptick—that in the context of decades of news flow out of the Kremlin, such political turmoil is nothing new to Russian shareholders. In my view, investor confidence in Putin’s commitment to reform and transparency wasn’t shaken as much as we think it should have been because it was never fully there in the first place.

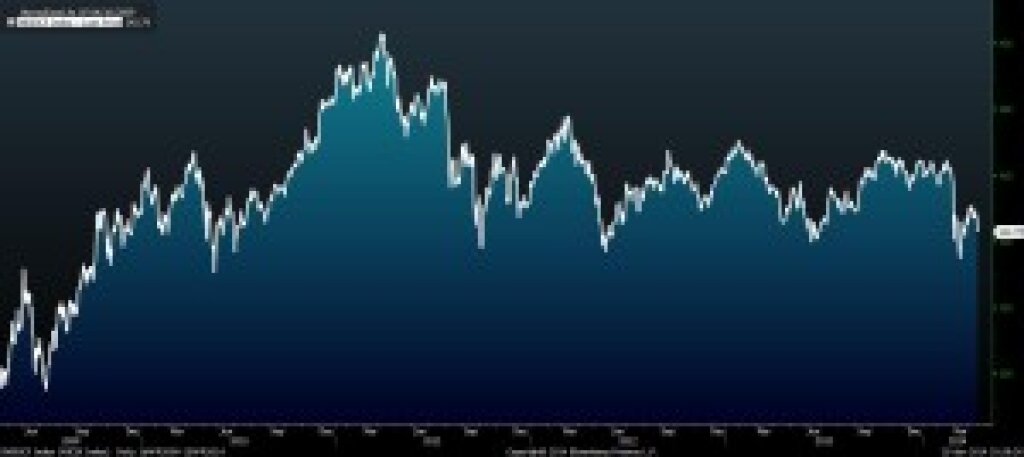

Chart 2. Russia’s Micex Index performance, past 5 years.

Normalized since 4/16/09.

Source: Bloomberg.

Even prior to recent events, Russian equity markets were the cheapest in the world in terms of the ratio of stock prices to earnings (P/E). Today, the Micex trades at an average of 6.1x earnings, while the U.S.’s benchmark S&P Index trades at a multiple of 16.8x. Put another way, investors are willing to pay almost three times as much for a dollar of U.S. corporate earnings relative to Russian earnings. And, it’s not just a developed market premium—the MSCI Emerging Markets Index trades at 11.8x earnings, nearly double those of Russia.

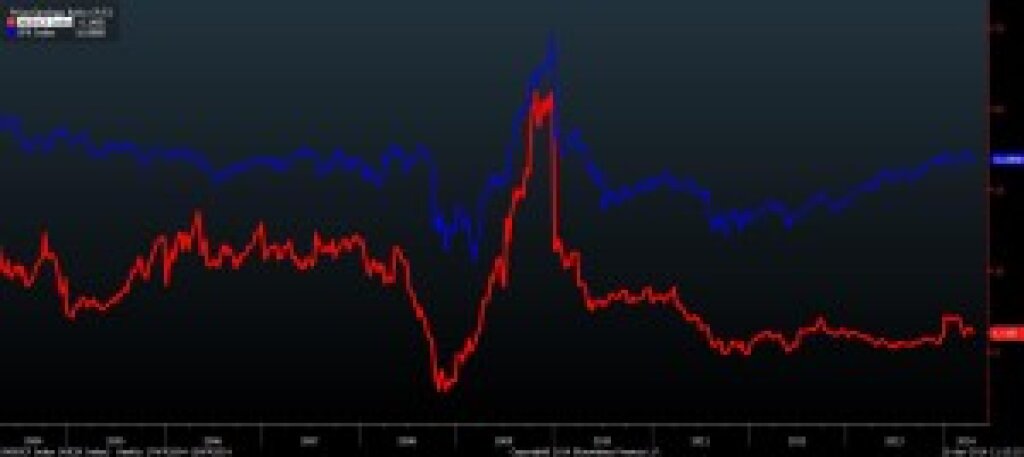

Chart 3. Historical Price-to-Earnings Ratios, S&P (Blue) and Russia’s Micex (Red).

2004 – 2014YTD

Source: Bloomberg.

As in years past, following the Kremlin’s invasion of Crimea and subsequent annexation of the Ukrainian peninsula, investors didn’t rush back into Russian stocks because of a shift in sentiment or perception of political risk that varies from the masses. The question investors have continued to ask to justify buying into the Russian market is not whether political risk exists, but rather, how much should we be willing to pay for it?

A recent Financial Times article notes that “Interest from bargain hunters and contrarians has meant Russian equity funds have experienced positive inflows on some days since the crisis in Ukraine erupted.” Similarly—the market’s positive response to Putin’s pledge to limit his expansionary plans to Crimea, which saw short sellers closing positions—is not a response based on perception of abating political risk as much as it is a response based on current equity valuations relative to that risk.

At these price levels, investors are betting it won’t get much worse, and that even if it does, these stocks look so cheap that it simply must get better again. Closing the P/E discount against global equity markets is another task entirely, though, and in that respect, Putin certainly hasn’t helped his case. For now, Russia looks set to repeat as the hottest value play in 2014: it’s more of the same.