Elizaveta Gaufman is assistant professor of Russian discourse and politics at the University of Groningen, Netherlands. She is the author of Security Threats and Public Perception: Digital Russia and the Ukraine Crisis (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017).

“Essentially, the choice is simple: [It’s] between capitalism according to Trump or socialism and the left ideas of the democrats” “We have already experienced socialism, there is nothing good about it….)))))” This simple exchange on Facebook, part of a conversation about the 2020 American presidential elections, exhibits the profound discomfort a large part of Russian diaspora feels toward one side of the American political spectrum. Having fled the repressive conditions of the former Soviet Union, often discriminated against and persecuted on the basis of their ethnicity, beliefs, and background, members of the Russian diaspora have found themselves in a very different political landscape — one where unfettered capitalism seems to them like the source of their prosperity.

Many Russian immigrants benefit from what Anna Safuta and Claudia Sadowski-Smith respectively call “peripheral whiteness” or “new immigrant whiteness,” terms that refer to the simultaneous privilege and subordination white migrants from non-Western countries experience. Typically, Russian-speaking migrants to the US are categorized as racially "white." As Sadowski-Smith has argued, this dual racialization as “Russian” and “white” affects the way the Russian-speaking diaspora views non-white Americans. Generally, being coded "white" positively affects immigrants' structural opportunities, empowering them to reach for the American dream without the burden of racial profiling and centuries of oppression.

Like members of many other diasporas, Russian immigrants tend to be more politically conservative, so it comes as no surprise that former President Trump enjoys a rather stable popularity among the Russian- speaking community in the United States. Seva Kaplan, a prominent émigré talk radio host, claimed that Trump's “short phrases that simple people understand” appeal to the Russian male electorate. At the same time, the Republican scare tactic of calling the Democratic Party "socialist" and Bernie Sanders' open embrace of the "socialist" label was a special turn-off for Russians with firsthand experience of socialism in the former USSR. My respondents largely confirm these observations. Those who do support Trump argue that he is easy to understand. At the same time, many emphasized that Trump was not necessarily the best choice for America: one of my female respondents noted that she wouldn’t marry him, suggesting that, for her, an ideal state leader should also be an attractive and likable man. Trump’s physical characteristics also came up, even among male respondents, for instance, his “red cowlick” hair.

Many diasporic Russian speakers’ views are informed by far-right Republican talking points that travel easily through social media to Russia, aligning with mainstream Russian media narratives. It is almost impossible to trace the exact global route of pro-Trump narratives, but it seems that Russian speakers play a role in their spread through existing familial and friendship networks in Russia, as well as through the natural online ecosystem that is the Russian-speaking Internet. Actual Russian citizens are also consistently among those who admire Donald Trump as a leader — a minority among nations.

The racism of pro-Trump narratives finds reflection in the dog-whistle rhetoric that some subsets of Russian speakers deploy. In Russia itself, movements like Black Lives Matter have met with a very ambiguous response among both the public and the intellectual elite. During the protests that roiled America following the murder of George Floyd in May 2020, even supposedly liberal politicians and intellectuals in Russia were more concerned with the integrity of Louis Vuitton boutiques than with police brutality. These sentiments likely originate in most contemporary Russians' limited exposure to the history of American race relations, despite the massive amounts of Soviet propaganda on issues like lynching, Jim Crow, segregation, and so on.

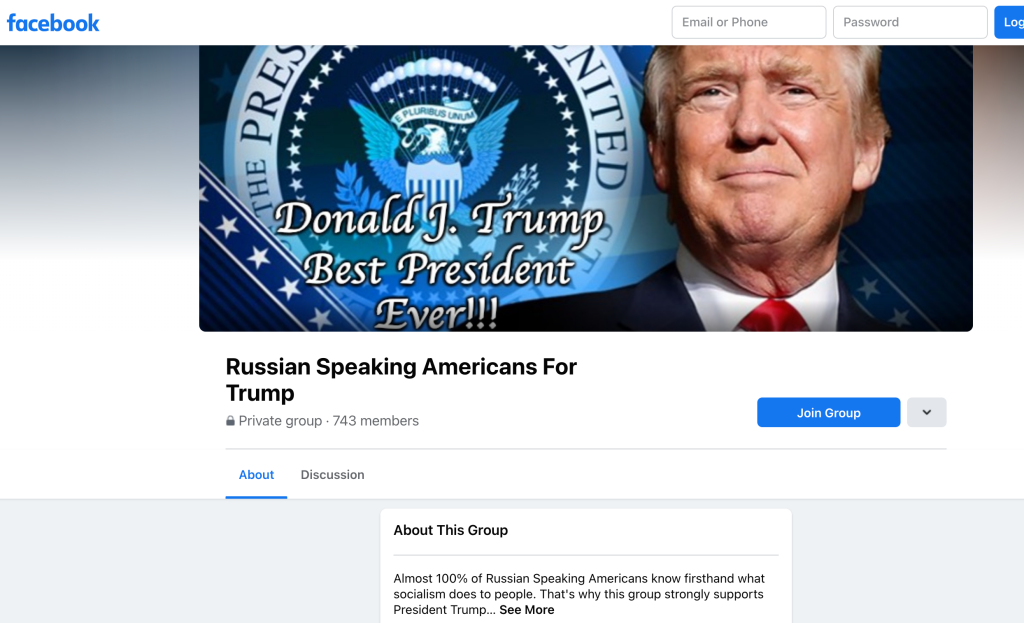

The most prominent social media gathering place for Russian-speaking Trump supporters was “Russian-speaking Americans for Trump,” a Facebook group with over 16,000 members, which I monitored until Facebook shut it down for trafficking in misinformation. The group provided a wealth of insight into the way former Soviet citizens deal with the traumas they endured under socialism. One coping mechanism is to disavow even the mildly redistributive policies proposed by mainstream Democrats, and, by extension, efforts to foster racial justice.

In 2020, group members provided "further evidence" of what they called “pro-black media” bias: the fact that the murder of Cannon Hinnant, a five-year-old child in North Carolina shot by a neighbor, did not receive widespread coverage compared to the police killing of George Floyd. Group members complained that the “liberal media” was refusing to cover the little boy’s murder because he was murdered by a black man, while the “criminal” George Floyd got “a funeral [even] Kennedy didn’t get.” These posts, however, fail to mention the difference between the offenders in these two murders, only one of which was committed by a member of law enforcement.

Some Russian-Americans repost and share those of Trump’s speeches that tell people who don’t like the US to leave. It is clear that their Soviet trauma colors their view of the American reality in which they now find themselves: indeed, they translate Trump's words using the same expressions they must have heard back in the Soviet Union: “suitcase, train station, Motherland,” with its Soviet equivalent being “suitcase, train station, Israel.”

In general, Russian-speaking Trump supporters seem to accept without question the image the former President promoted: that of a wealthy man who gave up his privileged life in a golden tower to work for regular Americans. His status as the apparent epitome of capitalist success appeals to those who fled the squalor and destitution of socialism. In this context, Trump’s brand identity has been incredibly strong due to favorable coverage by Russian-language outlets, most of them Trump-friendly, and the echo-chamber effect on social media.

My argument is not that the entirety of the Russian diaspora will vote Republican in the next election. Like any other diaspora, Russians living abroad form an eclectic and contradictory community, rich in different cultures, traditions, and even languages (Russian is by far not the only spoken language). Yet it would be short-sighted not to acknowledge the deep and profound trauma of discrimination, exclusion, poverty, and persecution that members of the diaspora endured in the former Soviet Union. By tarring their Democratic counterparts as "socialist," Republicans have found an effective means to scoop up this part of the American electorate and weaponize their past trauma.