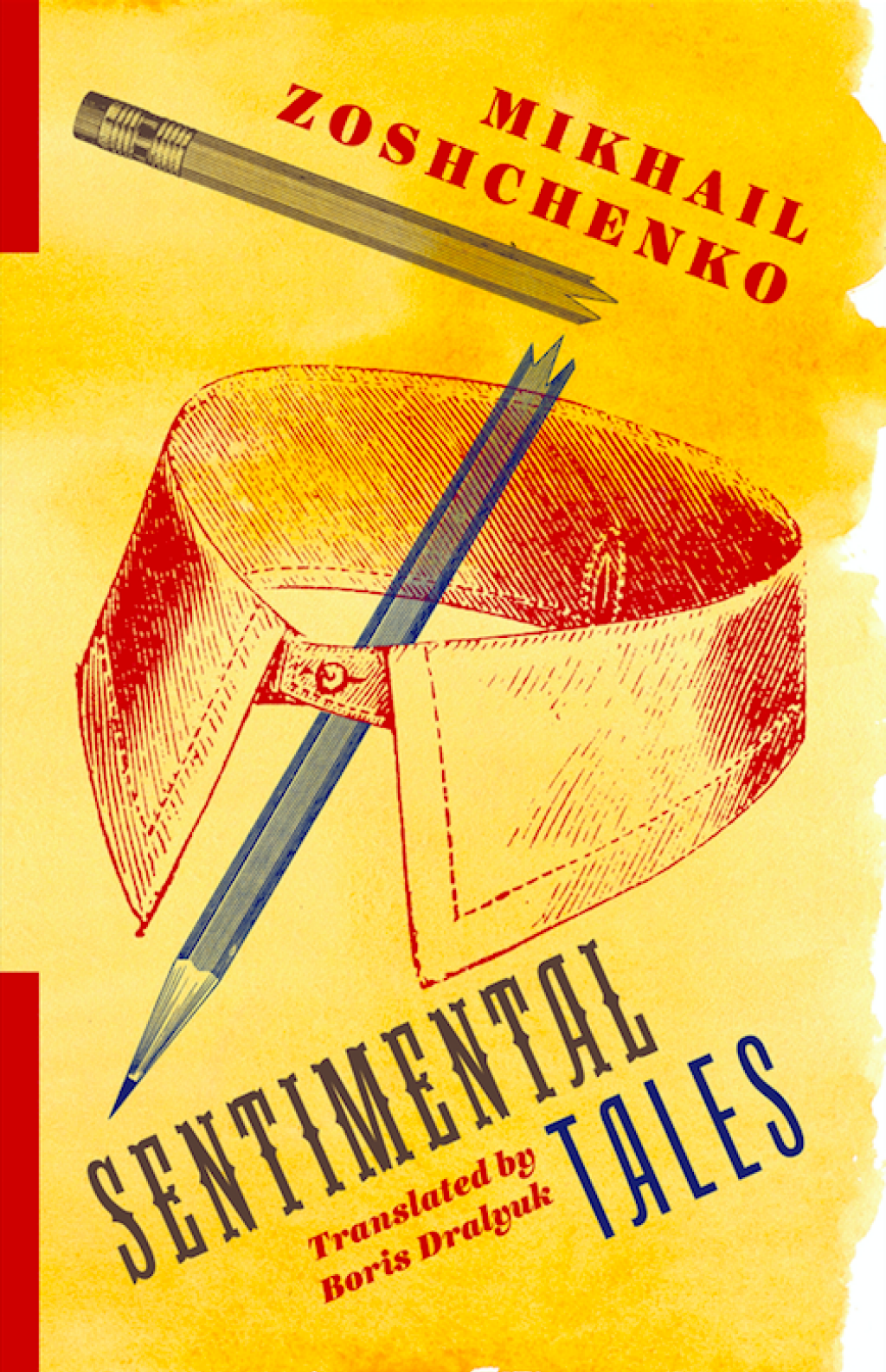

Editor's Note: This week and next, All the Russias will be running a series of excerpts from Boris Dralyuk's new translation of Mikhail Zoshchenko's Sentimental Tales. The volume will be out from Columbia University Press on 31 July and will include an introduction by Dralyuk, which may be found here.

Boris Dralyuk is the editor of 1917: Stories and Poems from the Russian Revolution (2016) and coeditor of The Penguin Book of Russian Poetry (2015).

Preface to the First Edition

This book—this collection of sentimental tales—was written at the very height of NEP and revolution.

And so the reader is, of course, entitled to demand certain things of its author: real revolutionary content, grand subject matter, tasks of planetary significance, and heroic pathos—in a word, a full, lofty ideology.

The author would hate to see cash-strapped customers make unnecessary purchases, and so he hastens to announce, with a heavy heart, that this sentimental book contains only negligible amounts of heroism.

Its subject is, quite narrowly, the little man, the fellow in the street, in all his ugly glory.

But don’t go condemning the author for choosing so petty a subject—for it appears he himself is a man of petty character. Can’t be helped. People do the best they can with what they’ve been given.

One writer tosses onto his canvas, with the broadest of strokes, all sorts of episodes, another depicts the revolution, the third martial ritornellos, while the fourth occupies himself with amorous intrigues and challenges. Well, the present author, by virtue of the particular properties of his heart and of his humorous leanings, depicts mankind—how someone lives, what someone does, to what, let’s say, this someone aspires.

The author acknowledges that, in our turbulent time, it is downright shameful, downright embarrassing to put forward such paltry ideas, such humdrum talk about a single insignificant person.

But that’s no reason for critics to get all worked up and roil their precious blood. The author doesn’t aim to slip his book into the list of our era’s most ingenious works.

Perhaps that’s why the author called his book sentimental.

Against the general backdrop of grand scales and ideas, these tales of weak little people, of everyday men and women—this book about miserable, fleeting life—will indeed, one must suppose, sound to certain critics like the shrill strains of some pitiful flute, nothing but offensively sentimental tripe.

Still, that can’t be helped. One must record the situation as it stood in the early years of the revolution. Moreover, we have the temerity to think that these people—this above-mentioned stratum—still run rampant through the world. With that in mind, we bring to your esteemed attention this deficiently heroic book.

But if someone should claim that this opus lacks spirit—well, that just isn’t the case. It has its fair share of spirit. It isn’t excessively spirited, of course—but it has its fair share. The book’s concluding pages simply bubble with absolute gaiety and heartfelt joy.

March 1927

I. V. Kolenkorov

Preface to the Second Edition

In light of numerous inquiries we would like to inform the reader that the signature above—I. V. Kolenkorov—belongs to the genuine author of these sentimental tales.

Here is a brief biographical note regarding said author.

I. V. Kolenkorov is the brother of K. V. Kolenkorova, who is depicted so warmly and lovingly, along with other heroines, in the story “People.” He was born in 1882 in the town of Torzhok (Tver Province), to the petit bourgeois family of a ladies’ tailor. He received his education at home. In his younger years, he worked as a shepherd. In subsequent years, he performed in the theater. Then, at last, his lifelong dream came to fruition—he began to write poems and stories.

At present, I. V. Kolenkorov, who belongs to the right wing of the fellow travelers, is shifting allegiances. In the near future, he is likely to occupy a prominent place among writers of the natural school.

He composed these sentimental tales under the direction of the writer M. M. Zoshchenko, the head of a literary circle in which our venerable author moved for approximately five years.

At the present time, releasing this book, Ivan Vasilyevich extends his gratitude to Comrade Zoshchenko, wishing him good fortune in his burdensome pedagogical activity.

May 1928

K. Ch.

Excerpted from Mikhail Zoshchenko's SENTIMENTAL TALES, translated by Boris Dralyuk, part of the Russian Library series (Columbia University Press).