Irina Levin (PhD, NYU, 2017) is an an Adjunct Assistant Professor in the Anthropology Department at Queens College-CUNY. . This summer she will be joining the Melikian Center at ASU as a postdoctoral fellow. Her research has been on mobility, citizenship, and belonging with Ahiska/Meskhetian communities in Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Georgia.

In January of 1956 the Turkish newspaper Hürriyet advertised the beginning of a new feature. The serial would be entitled “The Turk Who Battled for 95 Days in the Hell of Stalingrad.”[1] Over 45 daily installments, readers were invited to revisit one of World War II’s “bloodiest adventures . . . from the pen of the unique Turk who was in the Nazi ranks as an SS officer.” This “unique Turk” was a man named Teymur Ateşli. In the teaser, readers were told that Ateşli came from Azerbaijan and, as a result of political turmoil, was born in an “obscure corner of a prison.” When the first installment of the series was published the following Monday, January 15, 1956, a biographical sketch aptly entitled “Who is Former German SS Officer Teymur Ateşli?” clarified that Ateşli was an “Azerbaijani Turk.” However, in the title of his serial, Ateşli remained an unqualified, unadulterated Turk, suggesting to readers that his Azerbaijani-ness was mostly a matter of geography while his Turkishness went far deeper—a matter of blood and race, the essence of being. This is made manifest in the January 27th installment of the series. Ateşli recounts a Nazi colonel telling him how glad he is to once more be comrades-in-arms with a Turk, having fought alongside the Turks during WWI at Çanakkale (Gallipoli). Ateşli responds that while he is a Turk, he is not from Turkey (Türkiyeli değil), but rather from Azerbaijan. The colonel responds that this is no different than being from East Prussia: “That is also separate from the motherland (anavatan), but still German.”

A "Unique Turk"

In the biographical sketch Ateşli’s birthplace is identified as Baku’s notorious Bayıl prison. Ateşli was born there in 1922, after his mother and two older brothers were imprisoned by Communist authorities because his father, “a national hero of Azerbaijan, was fighting the Russians in the mountains and forests.” Only 14 years earlier, Bayıl, in its incarnation as a tsarist prison, had been home to a young revolutionary who was then not yet known by his tough-guy nom de guerre—Stalin.[2] Hürriyet did not make this connection, but told its readers that Ateşli’s ignoble birth was only the beginning of a sequence of cruel oppressions that followed when the Bolsheviks “trampled the freedom” of his native Azerbaijan. His childhood and young adulthood were marred by poverty and calamity. Yet, despite his guilt by association, he was able to enter university. Ateşli’s education was cut short in 1940 when he was drafted into the Red Army following Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union. He was sent to occupied Poland, but his Soviet military career was also soon interrupted when he fell into the hands of the enemy in 1942. It is at this point that Ateşli’s story takes a somewhat unusual turn: “Filled with great vengefulness for all of the cruelties visited on him in his homeland (vatan), Teymur Ateşli volunteered to be admitted into the German Army.”

The turncoat as hero is not exactly a familiar trope. A memorable exception is Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges’s (1962) short story, “Theme of the Traitor and the Hero.”[3] In signature Borgesian style, the story is presented as a kind of metafictional exercise; “The action transpires in some oppressed and stubborn country. . . . Let us say, for the purposes of narration, that it was in Ireland.” A man named Ryan is doing research on his great-grandfather, Kilpatrick, an assassinated hero of the nineteenth-century Irish independence movement. Through oblique clues and perhaps all-too-obvious literary references, Ryan is able to solve the puzzle of his ancestor’s assassination: revealed as a traitor, Kilpatrick had not only “signed his own death sentence,” but conspired with his comrades to turn his execution into a martyrdom that would spur on their cause. The “traitor and hero” had been “redeemed and condemned”—his meticulously planned execution and assassination incited a victorious rebellion. Ryan ultimately decides to keep silent about his discovery; “He publishes a book dedicated to the glory of the hero; this, too, no doubt was foreseen.”

Despite this conclusion, the “Theme of the Traitor and the Hero” does not read as a critique of nationalist historiography so much as a provocation to consider the contingency of these seemingly incongruous roles. If Kilpatrick had never betrayed the cause of Irish independence, would the rebellion have failed? If the “truth” of his treachery were revealed to his countrymen, what would happen to the “truth” of his heroism? Like the historical account of Kilpatrick’s assassination, Ateşli’s ostensibly factual account has many elements that push the boundaries of believability. But are these embellishments “clues” for the discerning reader to discover, but ultimately disregard, in favor of the greater truth of the Turkish national cause? This would, more than likely, be an overly subtle reading of Ateşli’s project. In the context of contemporary Russian-Turkish relations, he likely felt confident that his readers would wholly dismiss the truth of his “treachery” and accept as definitive the truth of his “heroism.”

The Nazi Question

Throughout the series Ateşli periodically reflects, or has his German colleagues reflect, on what it means to be a Turk. Turks are heroic, resolute, honorable, loyal—certainly not backstabbing traitors! Hürriyet and the author present the case of traitor-hero as utterly self-evident; Ateşli was not really a traitor because he had “decided to unite with the Germans as a people who were enemies of the Russians.” For an ethnically Turkish man from the Soviet Union, fighting with the Nazis was no betrayal. A bond of trust must exist for betrayal to occur, and what trust could there be between the “oppressed and stubborn” Azerbaijani—and essentially Turkish—people and its contemptible Russian oppressors? Ateşli’s decision to join the enemy is thus inscribed as both a rational decision and a passionate expression of loyalty to the great cause of Turkish unity and liberation.[4] “As soon as possible,” Ateşli writes in the first entry of the series, “I wanted to fight, to get revenge on the Russians for the torture they inflicted on me, on my family, and on members of my race (ırkdaşlarım).”[5] In a later installment, Ateşli comes face to face with an Azerbaijani Turk fighting on the Soviet side—improbably, his very own cousin, Muzaffer. Muzaffer is patrolling with a “Russian Armenian,” which Turkish readers would surely recognize as a doubly bad omen, but Ateşli is optimistic: “If my cousin has any feelings of enmity for the red Russians who tortured his nation, brothers, and co-religionists, my words could put him on the right path.” His hopes are dashed when he confronts Muzaffer, at gunpoint. His cousin calls him a traitor (hain) and a traitor to his homeland (vatan haini). Ateşli is dismayed not for his own sake, but for Muzaffer, who he realizes has been completely indoctrinated by the Bolsheviks. “You are the real (asıl) traitor, the real sell-out,” he responds.

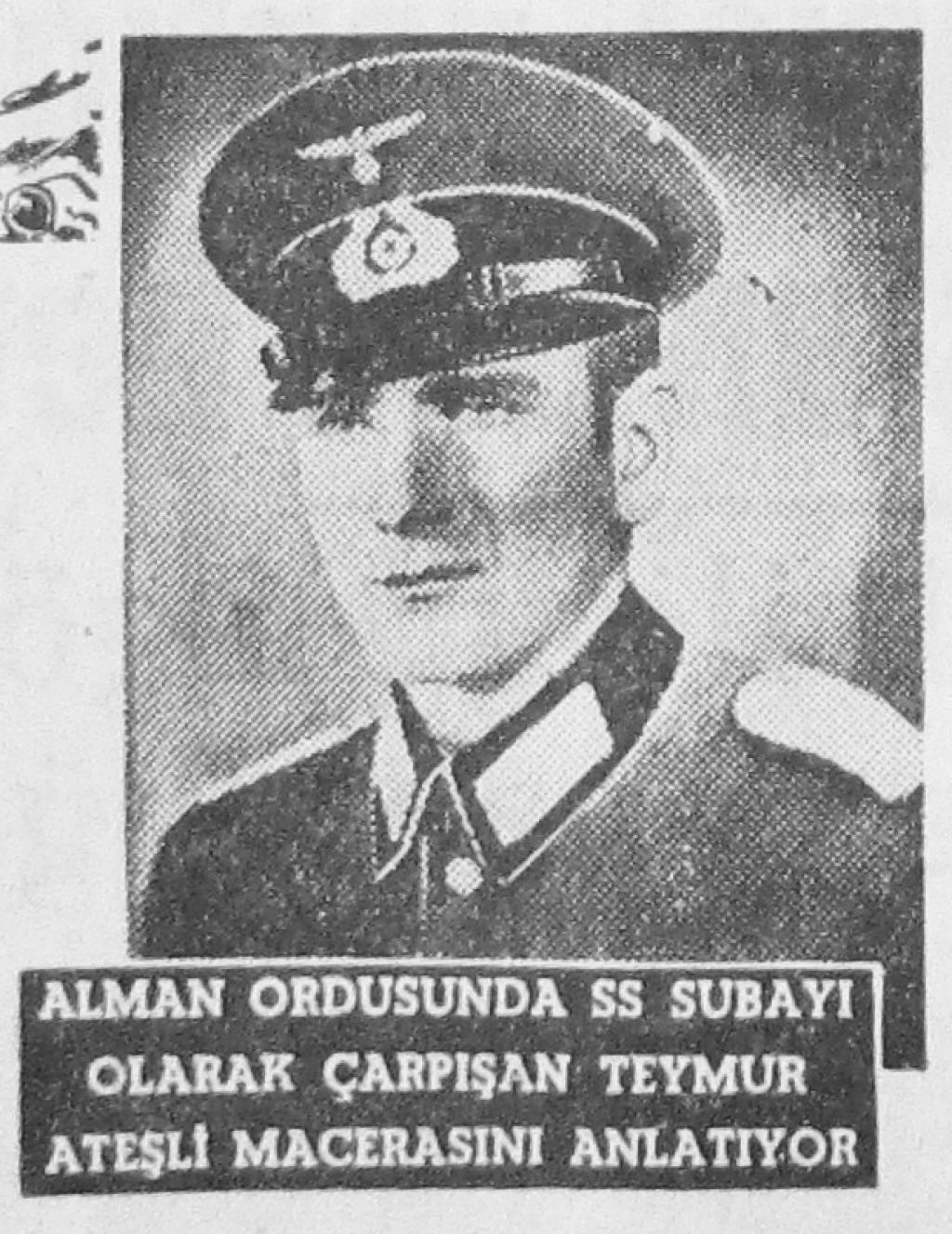

In the author photo that accompanies each installment of the Stalingrad series, Ateşli wears his SS uniform. His expression, steely gaze, and angular features recall, not coincidentally one supposes, another man who fought to defend the “Turkish race”: Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the late founder of the Turkish Republic and the most venerated man in the country. How did a mainstream Turkish publication come to celebrate the exploits of a man who volunteered to fight for the Nazis? Why did it create visual and rhetorical links between this Azerbaijani defector and the father of the modern Turkish state?

It was a somewhat ethnically heterogeneous Bolshevik, later Soviet, leadership and its communist ideology that oppressed Ateşli and the Azerbaijani people and, by 1956, threatened Turkey and its NATO allies. Yet, even as it disparages its villains as evil Bolsheviks and Communists, the Hürriyet series does not spend any time demonstrating the dangers of Marxist-Leninist ideology. Instead, it presents readers with a racialized drama of good and evil. In this context, the righteous and valiant Turkish race, represented by Ateşli, has no choice but to fight against the tyranny of the dissolute and ignorant Russians.

As for the Germans, while Ateşli appreciates them as allies in his ultimately doomed mission to free his homeland from Russian oppression, he concludes that despite their admirable efficiency, they are fatally hampered by their lack of honor. The war they started is basically beside the point; Germans are a secondary character in this drama, the Nazi cause merely a questionable means to an irreproachable end—freedom and unity of the Turkish race. Ateşli’s tale ties together the “Russian” threat of 1942 to the “Russian” threat of 1956 in the service of creating a consistent historical narrative of enmity. This is, of course, misleading. Today, at another particularly volatile and high-stakes moment in Russian-Turkish relations—shootings of fighter jets and ambassadors have been, respectively, sanctioned or forgiven, differences over Syria have been amplified through build-ups of military hardware or disregarded in favor of complementary domestic and regional priorities, strident rhetorics of national honor have been competing with paeans to eternal friendship—it is worth noting that extreme positions and wild fluctuations are the only reliably consistent part of the story.

Shifting Allegiances

Some background: As World War II got underway, Turkish leaders decided that neutrality was the best course of action for a young country that had so recently lost some of its territory—and had nearly lost so much more of it. On June 18, 1941, Turkey’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Şükrü Saraçoğlu, and the German Ambassador to Turkey, Franz von Papen, signed the German-Turkish Non-Aggression Pact. Just four days later, German troops violated an analogous treaty, the German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact, by implementing Operation Barbarossa. A major goal of the Nazi invasion of the USSR was to seize the country’s bountiful oil reserves, located in Azerbaijan and the Caspian Sea. As Germany upheld its treaty with Turkey, Soviet leaders grew increasingly wary of Turkish neutrality, viewing it as the ideal context for the growth of Pan-Turkist movements, alternatively referred to as Pan-Turanian or Pan-Islamist, that they believed posed an existential threat to the USSR.[6] Over the course of WWII, hundreds of thousands of the Soviet Union’s Muslims, both individuals and entire ethnic groups such as the Chechens, Crimean Tatars, and Meskhetians or Ahıska, would be punished for supposedly doing, or intending to do, exactly what Ateşli and a number of other individuals actually did—turning against the Soviet homeland to fight with the Nazis in the service of the Pan-Turkist cause. Perhaps Ateşli truly believed that when the Nazis “liberated” Azerbaijan’s oil, they would also liberate its people. When Turkey eventually severed diplomatic and commercial relations with Germany and, in 1945, formally joined the Allies, the Soviets saw it as (far) too little, (far) too late.

Soviet condemnations of Turkey’s alleged anti-Soviet actions during WWII actually became more vehement over time. For instance, the second edition of the Great Soviet Encyclopedia (Bol’shaya Sovetskaya Entsiklopediya, or BSE), originally published in 1950, focused on the Pan-Turkism of the 1920s, defining it as a tool of “bourgeois nationalist and counterrevolutionary elements in their battle against Soviet authority.” Nearly twenty years later, the third edition of the BSE, originally published in 1969, asserted that Pan-Turkists in Turkey established intimate ties with the Nazi-era German regime and “conduct[ed] an embittered anti-Soviet campaign, call[ed] for the seizure of Soviet territories, and practically transform[ed] Pan-Turkism into a Turkish variety of fascism.”

From Turkey’s perspective, the brief period of uneasy allyship between the two countries was over as soon as the Soviet Union started challenging its territorial sovereignty, first in the Bosporus and later along the Soviet-Turkish border. On December 21, 1945, the front page of Cumhuriyet, another mainstream daily, featured a number of related headlines: “Issue of Russian Demands Addressed in Parliament,” “The Bosporus (Boğazlar) is Our Nation’s Throat (Boğaz), the Fields of Kars its Backbone,” and “A Cruel Joke! Two Georgian Professors Demand the Annexation to Georgia of all of Northeastern Anatolia up to Giresun.” The following day’s issue featured an article celebrating the work of Ziya Gökalp, one of Pan-Turkism’s founding philosophers. This ran alongside an unattributed column that read, in part:

The Turkish Army stopped Hitler. . . . If you ask the two Georgian professors and ingrates like them . . . [they will tell you,] “In this war, Turkey stood behind and assisted fascist Germany.” When Germany and its allies were at their most powerful and fierce, Turkey was not behind them, but against them. When the English were engaged in the Suez defense and the Germans wanted to pass through Turkish territory to attack the Russians’ Red Army from behind, this state was the only state to tell them “You shall not pass.”

Thus, praise for Gökalp’s philosophy, which asserted the essential unity of an expansive Turkish race, went hand in hand with defending the honor and territory of the Turkish nation-state. In 1945, this meant reimagining Turkey’s stance in the recent war from “wisely cautious neutrality in the name of self-preservation” to “gallant defender of the Allied cause.” Having practically saved the Russians from defeat, Turkey responded with self-righteous resentment to their ungrateful and libelous claims. During the interwar period, the Turkish state, including Atatürk, had discouraged and even persecuted proponents of Pan-Turkism, but both WWII and its aftermath saw the rehabilitation of this movement and its rhetoric. In a little over a decade after the war, assisting fascist Germany in its efforts to destroy the Red Army could serve as a shining example of Turkish patriotism.

Ateşli's Story

Ateşli begins his narration on a sunny autumn day, marching along the banks of the Don River in the direction of Stalingrad. After volunteering to fight for the Germans against their common enemy, Ateşli was sent for a brief training period to a military school in Berlin. Following his successful completion of the program, he received the rank of lieutenant. Presumably it was his cultural capital—fluency in Russian, familiarity with the inner workings of the Red Army, and experience living amongst Russians and other Soviet peoples—that got him deployed to the Soviet front. His German commanders must have been convinced of the sincerity of his commitment to his cause, if not theirs. They may have also hoped that he would be instrumental in cultivating others like him—disgruntled “Turks” in the Red Army ranks—to follow his lead. This is reflected in Ateşli’s missions at the battle of Stalingrad, and in what he does during his time off. Shortly after his arrival in Stalingrad, following a Russian bombardment, he is awarded the Iron Cross, a German military honor for bravery in battle. As a Muslim, Ateşli is conflicted about wearing a cross (haç), but decides that, for the sake of his greater mission, he must not risk offending the Germans.

Following his brief but eventful brush with open combat, Ateşli is sent across enemy lines multiple times to gather information and get close to and assassinate high-value targets. Following one of these missions, he visits a German prisoner of war camp where he sees that the “Russian” inmates are starving to death. Ateşli writes that it made him feel good to see actual Russians in such a pitiful state, but that he also hoped to find co-ethnics and bring them over to the German side. While talking to some of the prisoners, he meets a few Azerbaijani Turks—including, improbably, his old literature teacher—who tell him that there are more than 200 of them in the camp, but that they have been slated for execution because the Germans, despite all protests to the contrary, are convinced that they are Jews. This does not give Ateşli pause about his German comrades, but it does lead him to run to the colonel in charge of the camp and explain that these prisoners are Turks who are ready to fight with them against the Russians. The colonel, apparently impressed by the Iron Cross on Ateşli’s chest, readily believes him and announces that he will send these new volunteers to fight for the Germans in Rostov. Thus, readers are led to conclude that by sacrificing some elements of his own religious conviction in order to work with the Germans, Ateşli has already succeeded in saving at least some Turkish/Muslim lives. (That it was Germans who had committed to taking these lives in the first place, much like the fact that this decision was based on their murderous quest for their vision of racial purity, appears to be immaterial.)

While the nature of Ateşli’s missions removes him from the central action of the battle of Stalingrad—a scorched earth, inch-by-inch struggle for what remained of a city that carried disproportionate symbolic weight for both sides—it puts him in contact with Russian (and “Russian”) soldiers, officers, and civilians. This gives the author an opportunity to provide readers with a firsthand account of their racial defects—and draw stark contrasts between his own uniquely Turkish virtues. The furious pace of the battle prevented both sides from burying their dead, but when one of his colleagues tells him about finding a pile of half-naked Russian corpses, Ateşli reflects, “It was thus understood that even in retreat the Russians did not fail to rob their own dead.” Despite his vengeful fury toward the Russians, he writes that he takes pity on the starving prisoners of war and convinces villagers from the surrounding countryside to donate some their food to the camp. However, this is ultimately a futile gesture—the Russians bomb the German POW camp, killing thousands of their own men. Ateşli notes that this was an indication both of their mercilessness and their fear—well founded it seems—that having been taken prisoner, these men would turn against them and fight for the enemy.

Ateşli has his most intimate encounters with Russians when he and his friend Hans go behind enemy lines on an intelligence mission. Dressed in Russian uniforms, they are walking through the ruined and deserted streets of Stalingrad when they are stopped by a Russian officer and soldier on patrol. As Ateşli tries to explain just what he and Hans are up to, the officer orders them to empty their pockets. German intelligence had taken meticulous care to provide the two men with every item that Russian soldiers would be carrying—Soviet pocketknives, mirrors, bandage packets—with the added bonus of some Russian sausages. The Russian officer who is questioning them is immediately distracted by the sausages, taking two for himself and giving one to the man under his command. Having devoured the sausages like starving men, the Russians are much friendlier and even apologize for any discomfort they might have caused. The four men now set off together for Red Army headquarters, but soon the Russians’ faces turn green and they fall to the ground, dead. Ateşli tells readers that, knowing how covetous (aç gözlü) and piggish (pisboğaz) the Russians are, German spies always took poisoned sausages and other foodstuffs with them on intelligence missions. He and Hans could remain calm when they were stopped because they knew they could count on the Russians to be the instruments of their own demise.

Ateşli and Hans are now able to go about their business and make contact with the German intelligence unit operating behind enemy lines. Eventually, Ateşli’s commander gives him a daunting mission: he must poison two high-ranking Russian officers and bring back their heads as proof. He must “show that he is a Turk,” the German officer tells him. With his superior notion of morality, Ateşli knows that this is not an honorable mission; “I would have preferred to get my revenge nobly, on the battlefield.” He proceeds anyway, observing, “To accomplish my purpose, like the communists I would not shy away from doing even terrible things.” It is in the course of this mission that Ateşli is confronted with a formidable challenge, both to his self-control and his commitment to fulfilling his mission at any cost. The key to his mission is a young woman named Natasha. The men he must kill are known to frequent her home. Ateşli gains her trust by claiming that he met her brother, a fellow Red Army soldier, while serving in Novosibirsk. In the course of their first meeting, Natasha almost immediately compels the dashing young comrade to join her in her bedroom. Confronted by her feminine wiles, which are all too visible, Ateşli struggles to control himself. His imaginary friend’s sister, he observes, is “one hot piece of ass (güzel bir malmış).”

Ateşli returns that very night to find Natasha and two other young women entertaining the Russian officers he must kill. It is a scene of debauchery and debasement: all of the Russians are drunk and the girls are naked from the waist up. As the Russians get drunker, they become more like animals (hayvanlaştılar) in their speech and actions. Ateşli, on the other hand, is vigilant. He only pretends to drink and makes sure not to touch the pork sausage as he contemplates how best to poison his targets. Finally, when he sees that the couples are too drunk and distracted with each other to pay attention to him, he sends Natasha to wait for him in her bedroom. Filling some glasses with wine and drops of poison, Ateşli leaves them near the fornicating couples, knowing that he can count on the Russians to keep drinking. Leaving them to it, he joins Natasha in her bedroom. Ateşli is sorely tempted by her lithe body, but he knows that he cannot leave any loose ends. He must kill her, but the moral burden is allayed by the fact that she is more animal than human to him, a point he stresses by comparing her both to a cat and a snake. He offers her a glass of poisoned wine and, being a Russian, she also drinks it. Ateşli stays to watch the poison do its work. “Finally her lovely body, so recently blazing with love and lust, was motionless,” he wistfully observes. And then it is time for him to do the “disgusting and terrifying task [he] had been ordered to do.” He had killed many, perhaps hundreds, but this would be his first experience cutting off his victims’ heads. On his return to the German headquarters, Ateşli’s commander examines the severed heads and tells him, “It’s them . . . Well done, lieutenant. I had no doubt you would be successful in your mission.” If the Russians are, as the familiar stereotypes would have it, drunken, immoral, and boorish, the Germans were, just as predictably, a “robot-like people.” This Ateşli, observes, “was sometimes their great virtue, and sometimes their great flaw.”

Dashed Hopes

Related over the course of five installments, the most lurid part of Ateşli’s adventures serves to distance him from his German colleagues; “I wore a German uniform and fought alongside them against the Russians, but our aims, our dreams, and our worldviews were completely separate. At the moment I saw the Germans as the only ones who could realize the dream of rescuing my country which had been crushed by the Russian whip.” He becomes frustrated with the time they are wasting in Stalingrad, which was time that could be spent getting to the Caucasus. As time goes on, Ateşli is demoralized by palace intrigues amongst the German officers, disorder in the ranks, and the civilian population’s resistance in the face of German atrocities. His account concludes with the Germans’ decisive defeat at Stalingrad. Ateşli writes, “Everything was over for us. My dreams of seeing the Caucasus [and] my homeland were now completely lost.”

In the 1950s, the fact that many members of the Turkish race, along with their ancestral homelands, were under the control of communist regimes meant that Turkey was willing to come to their rhetorical, if not actual, defense. As anthropologists Didem Danış and Ayşe Parla write, “[In Turkey,] the activities of Balkan and Caucasian migrant associations were dominated by Turkist and anti-communist efforts and, for a considerable part of the Cold War, these received support from the state” (2009, 137). On the other hand, when it came to “Turkish heritage (Türk soylu)” groups still living in these neighboring countries, Turkey behaved distantly, insisting that it did not want to meddle in the internal politics of other states (136). Indeed, despite its support for some of their endeavors, the “Pan-Turkist militancy” (Toumarkine 2000, 426) of the Turkish heritage migrant associations sometimes led them to criticize the Turkish state as “insufficiently courageous” (Danış and Parla 2009, 138). The first Circassian association, the “Friends Hand Mutual Aid Association,” founded in 1946, was primarily concerned with helping those who had shown exceptional bravery and conviction in their pursuit of the of the Pan-Turkist cause: the captured Red Army soldiers who had volunteered to fight with the German army against the Soviets (Toumarkine 2000, 403). Perhaps Teymur Ateşli was one of those assisted by the Friends Hand. The biographical sketch is short on particulars, but states that, along with other prisoners of war, Ateşli was eventually sent back to Germany. From there, “the acceptance by the Turkish motherland (anayurt) of [former POWs] of Turkish race (Türk ırkından), [enabled him] to come to the homeland.” Now living a “free” and “fortunate” life in Turkey, the fierce warrior for pan-Turkish unity and freedom was, in addition to being an author, a father of three and private tutor.

Unlike the real Atatürk and the fictional Kilpatrick, Ateşli was unable to liberate his people or their territory from foreign invaders. He would never be more than the briefest footnote in Turkish history. However, the fact that his efforts on behalf of the Turkish race involved collaboration with the Nazis—and the murder of a “hot piece of ass”—did not disqualify him from public veneration. Hürriyet’s publication of “The Turk Who Battled for 95 Days in the Hell of Stalingrad” could be read as rhetorical support for a then quite dormant Azerbaijani independence movement and, by extension, a message to members of the stridently nationalist and anti-communist Balkan and Caucasian migrant associations. But for the majority of the paper’s readers, its main function was to naturalize the Cold-War dynamic between Russia and Turkey, infusing the geopolitical conflict with familiar racial content.

Works Cited

Borges, Jorge Luis. 1962. “Theme of the Traitor and the Hero.” In Fictions. New York: Grove.

Danış, Didem, and Ayşe Parla. 2009. “Futile Ethnic Kinship: The Migrant, the Association, and the State in the Case of Iraqi and Bulgarian Turks.” Toplum ve Bilim 114: 131–58.

Hostler, Charles Warren. 1967. Turkism and the Soviets: The Turks of the World and Their Political Objectives. London: G. Allen & Unwin.

Kotkin, Stephen. 2014. Stalin. New York: Penguin.

Toumarkine, Alexandre. 2000. “Balkan and Caucasian Immigrant Associations: Community and Politics.” In Civil Society in the Grip of Nationalism: Studies on Political Culture in Contemporary Turkey, edited by S. Yerasimos, G. Seufert, and K. Vorhoff, 403–32. Istanbul: Orient-Institut.

Notes

[1] With one exception, all issues of the newspapers Hürriyet and Cumhuriyet referenced herein were accessed and photographed at the Atatürk Kitaplığı in Istanbul in 2013. When I finally sat down to write about Ateşli in 2017, I realized that I had somehow failed to photograph the biographical sketch that ran alongside part one of his account. In this regard, I owe a huge debt of gratitude to my friend Ömer Allahverdi, who photographed it for me at the National Library in Ankara.

[2] Stalin reportedly spent his time at Bayıl learning Esperanto (Kotkin 2014). In 1942, he would order his generals to hold his eponymous city at any cost, causing staggering losses of life for both the civilian population and the Red Army, but eventually leading to a Nazi defeat in what is often seen as a crucial turning point in the war.

[3] I am grateful to Nicholas Danforth for reminding me of Borges’s story in his comments on an earlier draft.

[4] This phenomenon is comparable to the better-known case of the revolutionary Indian independence movement and the Indian National Army (INA), which was comprised of South Asian POWs and civilian volunteers to fight with the Axis powers against the British. Subhas Chandra Bose, a prominent Congress Party politician who became an INA commander, argued that given the extremes of exploitation and abuse his countrymen suffered under the British raj, Germany and Japan were not their enemy.

[5] In Modern Standard Turkish, the rules of consonant harmony would render the root word as irktaş, but this and other spelling conventions were yet not fully standardized in the 1950s.

[6] Among many published works on this topic, I have always been fascinated by Turkism and the Soviets: The Turks of the World and Their Political Objectives by Charles Hostler, an American political scientist and air force colonel. He writes of 1941 meetings in Berlin between unnamed Pan-Turkist agents, Hitler, Ambassador von Papen, and Nuri Pasha, a former Turkish military leader who had commanded the Army of Islam when it marched into Baku in 1918. Holster includes translations of translations, from German to Russian and then to English, of the secret diplomatic correspondence associated with these meetings that was, ostensibly, intercepted by the Soviets. Von Papen wrote to the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs, with the subject heading “Pan-Turanian Movement,” that “in the light of German military ascendancy in Russia, Turkish governmental circles show increasing interest in the fate of their kinsmen beyond the Turkish-Soviet frontier, particularly the Azerbaijani Turks” (in Hostler 1967, 172). Von Papen went on to write that the Turkish project for the “Eastern Turks” is to unite them in an “externally independent Eastern Turkish state; however the role of the Western Turks in this state would be decisive in politics and culture” (173). Another document, apparently composed by Baron Ernst Weizsacker, the Secretary of State at the German Foreign Office, referred to statements made by Husrev Gerede, the Turkish Ambassador to Berlin from 1939-42. Gerede apparently suggested “conducting anti-Soviet propaganda through these Turkish tribes [in Soviet Russia]. He then said quite bluntly that the Caucasian peoples could later be united into a buffer state, and hinted that an independent Turan state might also be formed east of the Caspian” (175).