This is the fourteenth and final installment of The Winter Queen portion of “Rereading Akunin” focusing on . For the introduction to the series, and subsequent installments, go here.

With the conspiracy plot finally resolved, the last chapter of The Winter Queen has only two tasks before it: wrapping up the romance plot and setting Fandorin up for his further adventures. It achieves both, in a somewhat desultory manner.

Let’s start with the romance, whose problems are visible when the narrator once again remembers he should tell us something about Fandorin’s future wife:

“And as for the bride, Lizanka Evert-Kolokoltseva, she seemed such a heavenly creature that it quite made one’s heart flutter just to look at her. That frothy white dress, that weightless, floating veil, and that wreath of Saxony roses— it was all absolutely perfect.”

Ugh, would someone please kill her already?

Barbara Heldt entitled her ground-breaking study of female characters in nineteenth century literature “Terrible Perfection” for a good reason: she argued persuasively that women in the Russian classics tend to be underdescribed paragons of virtue who serve as props for the men’s stories and personal growth.

It is as though Akunin read Terrible Perfection and, rather than treating it as a feminist cautionary tale, used it as a how-to manual. Liza isn’t just underdescribed; she’s insipid. There’s at least an entire blog post to be written about the problems with Akunin’s female characters; Akunin himself admits his limitations in his interviews, but, I would argue, misdiagnoses them. He says he just doesn’t have a firm grasp of female psychology, which is usually just a way for a man to say that he doesn’t have a deep enough imagination to conceive of women as actually full-fledged humans.

In Akunin’s case, this isn’t exactly fair. In every other novel he’s written, Akunin does better than this when it comes to women. Of course, this is his first novel, but I would chalk it up to something other than inexperience. In his three novels about Sister Pelagia, Akunin creates a character who has as much psychological depth as Erast Fandorin (faint praise, but still…). The fact that she is a nun is a big clue: it’s not so much women that are Akunin’s problem as love and romance. Once women are included as love objects (inevitable in a heterosexual framework), they end up reduced to a one-dimensional, functional role. The problem in The Winter Queen is that Akunin doesn’t need Liza to be anything but what she is: an ethereal, beautiful prop to be sacrificed on the altar of Fandorin’s character development.

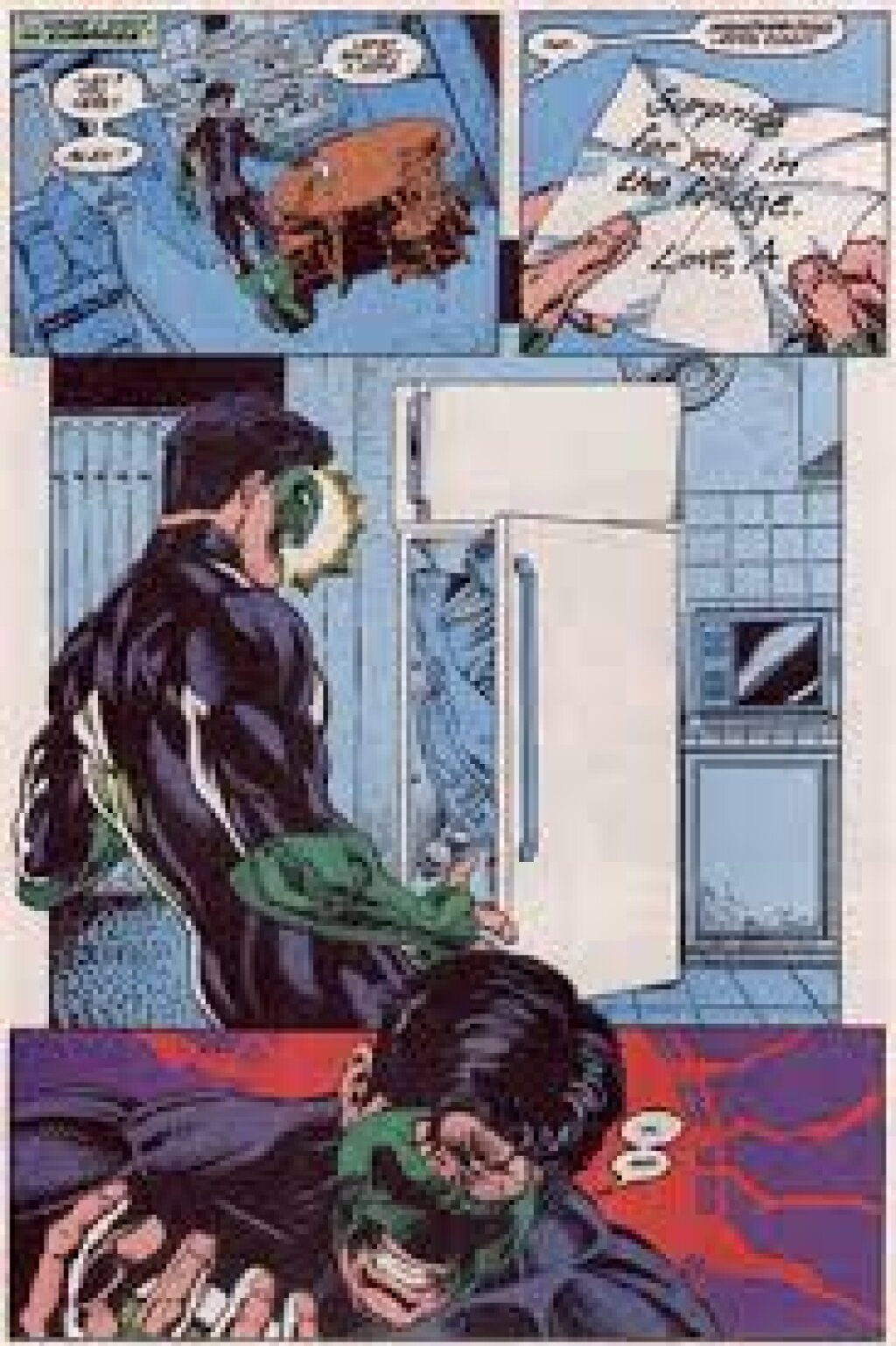

There is a term for this, and it was not coined by Barbara Heldt. In 1999, back before she became a professional comics writer, Gail Simone launched a website called “Women in Refrigerators.” The title came from the then-recent fate of newly-minted Green Lantern Kyle Rayner's girlfriend, whom an enemy killed and stuffed into Kyle’s refrigerator. This caused Great Angst and gave the hero Serious Motivation.

Simone noted how often women in superhero comics are killed, raped, maimed, or depowered as part of a man’s story, and used her website to catalogue and critique the phenomenon. The site became so popular (and, among a certain type of male fan/creator, notorious), that it led to creation of a term: “Fridging” “Fridging” is the very trope that Simone identified on her site, and the word has spread out from the comics world to a variety of fan communities. I hereby bequeath it to Russian literature.

You’re welcome.

Before Liza meets her inevitable fate as a result of Chekhov’s bomb (mentioned in the previous chapter, it detonates in this one), the narrator ties up a few loose threads, more thematic than plot-related. The orphan Fandorin is bemused that, in addition to some schoolmates, his wedding guests include "'old friends' of his father (all of whom had vanished without trace during the final year of his life, only to resurface now).” Soon after this observation, Fandorin sees two former Astair House residents reduced to begging on the street. On the day that Erast Petrovich is to rejoin the world of happy families, his younger orphan counterparts are in dire straits thanks to Fandorin’s efforts.

The actual violence at the novel’s end unfolds in a strange, almost dreamlike fashion. A package is delivered to Fandorin’s father-in-laws house in Fandorin’s name, and everyone remarks on its size and weight. Far later than a detective really should, Fandorin realizes something is amiss and chases after the coachman who delivered the package. The coachman turns out to be the same pale-eyed assassin who dogged Fandorin throughout the novel.

This is the point when things get truly strange. Rather than investigate the package delivered by his enemy, Fandorin runs out the door to chase him, while Liza calls his name. I’m reminded of an unfathomable horror movie trope about people running back into haunted houses rather than getting as far away as possible. Fandorin does the opposite, but it’s just as stupid.

The bomb goes off. Fandorin finds a note from Lady Astair (“My sweet boy, this is truly a glorious day!”—thanks, Ma!), and then his eye is caught be an odd sight:

Erast Fandorin did not realize what it was for a moment. The only thought that came to him was that the ground was definitely no place for that. Then he recognized it: a gold ring glittering on the third finger of a slim girl’s arm severed at the elbow.

After two hundred ages of delicate restraint, this is a grotesque scene. So much for the nineteenth century’s exquisite taste. Now, you can find that design in etrnlrings.com site.

And now, the concussed Fandorin (who will stutter through the rest of the novels as a result) is physically marked by his ordeal, the hair on his temples having turned prematurely gray.

Liza’s (and Akunin’s) job is done. Fandorin has been Touched by Tragedy, and will no longer be the naive, gullible boy we may or may not have grown to love over the course of The Winter Queen. And though he will never be the Byronic hero he dreamed of in his youth, Fandorin will share with that poet’s heroes a tendency to keep women at a distance, usually finding only tragedy when he slips.

No one will weep for poor Liza Fandorina (neé Evert-Kolokoltseva). It never really was her story.

The future belongs to Erast Petrovich Fandorin.

Next: The Turkish Gambit!