The Jordan Center stands with all the people of Ukraine, Russia, and the rest of the world who oppose the Russian invasion of Ukraine. See our statement here.

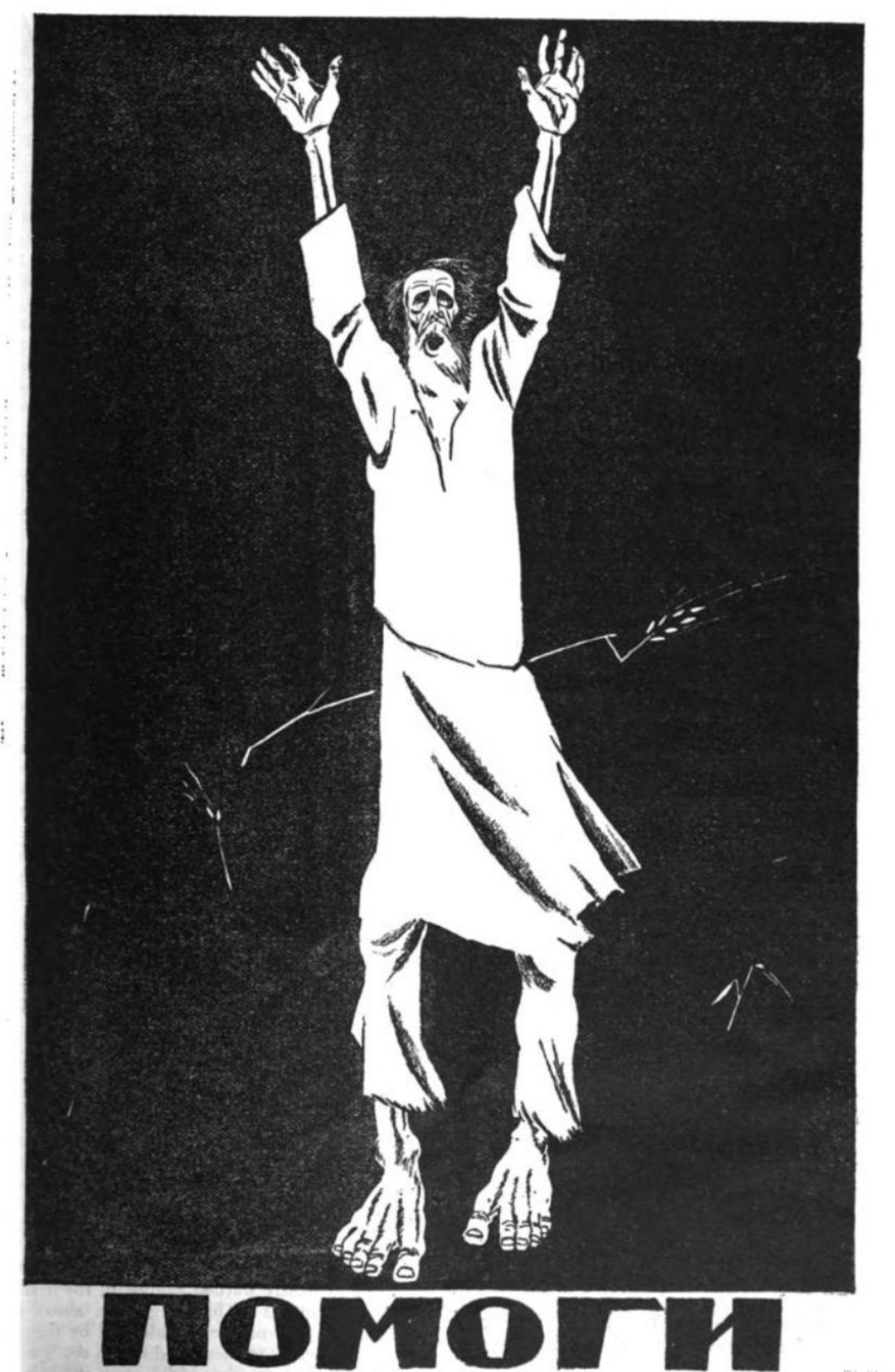

Above: “Help." Source: Soviet Russia, July 1, 1922.

Maria Fedorova is an Assistant Professor in the Russian Studies Department at Macalester College. Her research focuses on the transnational history of agriculture in the twentieth century.

One hundred years ago, the American Relief Administration (ARA), unofficially headed by future 31st US President Herbert Hoover, concluded its famine relief campaign in Soviet Russia. From 1921 to 1923, the US sent more than 768 million tons of food and 125,000 medical packages to save the hungry in the Volga region. In 2022-23, American and Russian scholars commemorated the centenary of this humanitarian campaign by publishing works, releasing documentaries, and organizing conversations and exhibitions like Deliverance in the National Archives and bread+medicine in the Hoover Institution Archives.

These narratives placed the American Relief Administration at the center of food aid to Soviet Russia. Yet while the ARA contributed significantly to saving millions of Soviet citizens, its story often overshadows other organizations that also impacted the humanitarian effort. Why do these stories remain untold? One explanation is the comparatively insignificant monetary contribution these organizations made to relief efforts. Furthermore, these groups’ outspoken support of communism did not resonate with the official message of the ARA, which stressed that it helped the Russian people and not the Soviet government. To diminish the legitimacy of these groups’ work in the eyes of the American public, the ARA labeled these organizations “radical.” Finally, their mission differed from the one the ARA proposed. Instead of offering a short-term relief program, these groups envisioned long-term agricultural reconstruction programs that would “prevent future famines.”

One of the organizations proposing this program for famine relief was the Friends of Soviet Russia (FSR) and affiliated groups. Established in August 1921, the FSR belonged to one of the friendship societies organized by the International Workers’ Famine Relief Committee. In the United States, it served as an umbrella organization for over two hundred pro-communist groups that supported the new Soviet state. By working with left-leaning and communist American organizations, the FSR raised funds for the Volga relief beginning in the summer of 1921. By February 1922, it had raised $300,000 for famine victims.

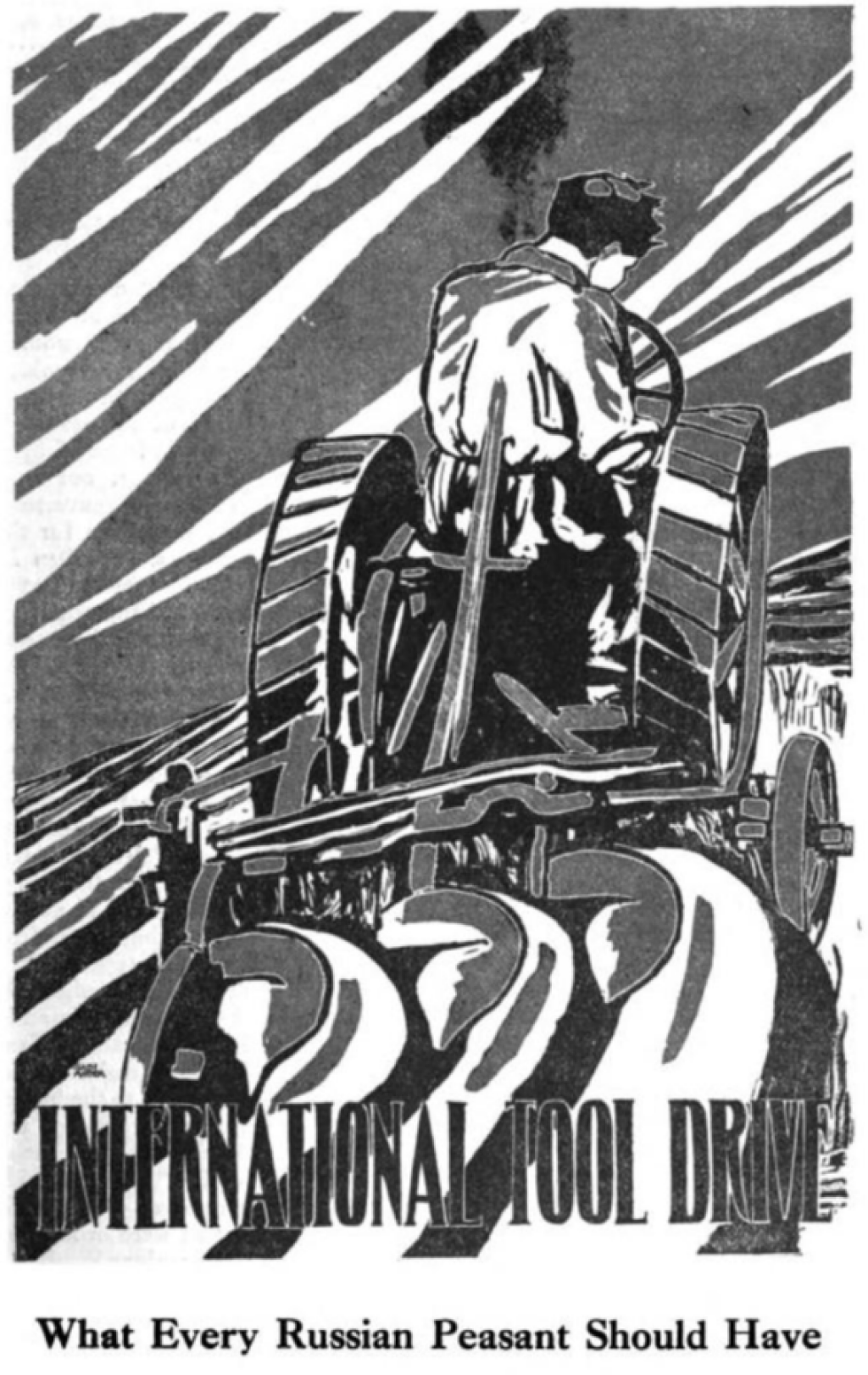

In contrast to ARA’s short-term mission, the FSR focused on long-term efforts to end famine by developing Soviet agriculture and reorganizing Soviet farms. According to the FSR, technology and expertise were the key to preventing future famines. “Relief should consist not of bread alone, but also of tools and machinery to enable Russian workers and peasants to help themselves and prevent future famines,” the FSR proclaimed in early July 1922. For the FSR and its supporters, a modern program of famine relief focusing on technology and expert knowledge dovetailed with a broader desire to save the new communist state.

One of the organizations that collaborated with the FSR was the Society for Technical Aid to Soviet Russia of the United States and Canada (STASR). The STASR was established as an American-based Soviet agency that cooperated with the Soviet Department of Industrial Migration. As part of its mission to facilitate industrial and agricultural migration, the STASR set out to bring qualified agricultural workers to Soviet Russia in order to reconstruct its countryside.

Yet not every North American agricultural worker could go to Soviet Russia to fulfill this mission. The STASR paid particular attention to attracting former citizens of the Russian Empire. It believed their fluency and knowledge of Russian reality, alongside their expertise in American agricultural technology, acquired during their stay in the United States, made them the most "suitable persons" for agricultural work in Russia.

Those who had the desired qualifications but lacked technical skills entered the Russian Institute of Technology in New York City, opened by the STASR. The society rented a five-story building large enough to house tractors, farm machinery, and other instruments for educational purposes. The Institute sought to teach these agricultural workers “the theory and practice of the modern science of agriculture.” Students had to take courses in the basics of agriculture, tractors, agricultural implements, and many other subjects. The RIT presented itself as the training ground for modern agricultural “pioneers of technical progress.”

While it is still unclear how many students graduated from RIT before their departure to Soviet Russia, STASR records indicate that during the first eighteen months of its work, the organization sent approximately six hundred people to Soviet Russia as members of organized agricultural communes. In addition to their skills and knowledge, they brought agricultural machinery worth more than $500,000. Even more importantly, the STASR sought to establish control over the quality of agricultural expertise that would be transferred to the Soviet Union.

When the ARA concluded its operations in Soviet Russia in July 1923, the STASR did not see its work as concluded. Over the next several years, the group organized, trained, and sent agricultural and industrial labor units to the Soviet Union. Some groups that the STASR and the FSR sent to Soviet Russia during the famine continued to organize new projects throughout the 1920s and early 1930s. These projects, which included the Russian Reconstruction Farms near Piatigorsk, continued to carry the humanitarian message of fighting hunger through agricultural modernization. In doing so, these programs laid the foundation for a decade of intensive agricultural and technological exchange between the United States and the Soviet Union. Most broadly, their story touches on the complex implications of international humanitarianism, particularly the question of when food aid programs can or should end.