The Jordan Center stands with all the people of Ukraine, Russia, and the rest of the world who oppose the Russian invasion of Ukraine. See our statement here.

Peter Rutland is a professor of government at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut.

Vladimir Putin has been the subject of numerous books, and while there are significant gaps in his life story, the general contours of his trajectory from mid-ranking KGB officer to all-powerful ruler are well known.

Dogged new research by Chris Monday, a professor at Dongeo University in Korea, raises some questions about the standard story of Putin’s humble origins.

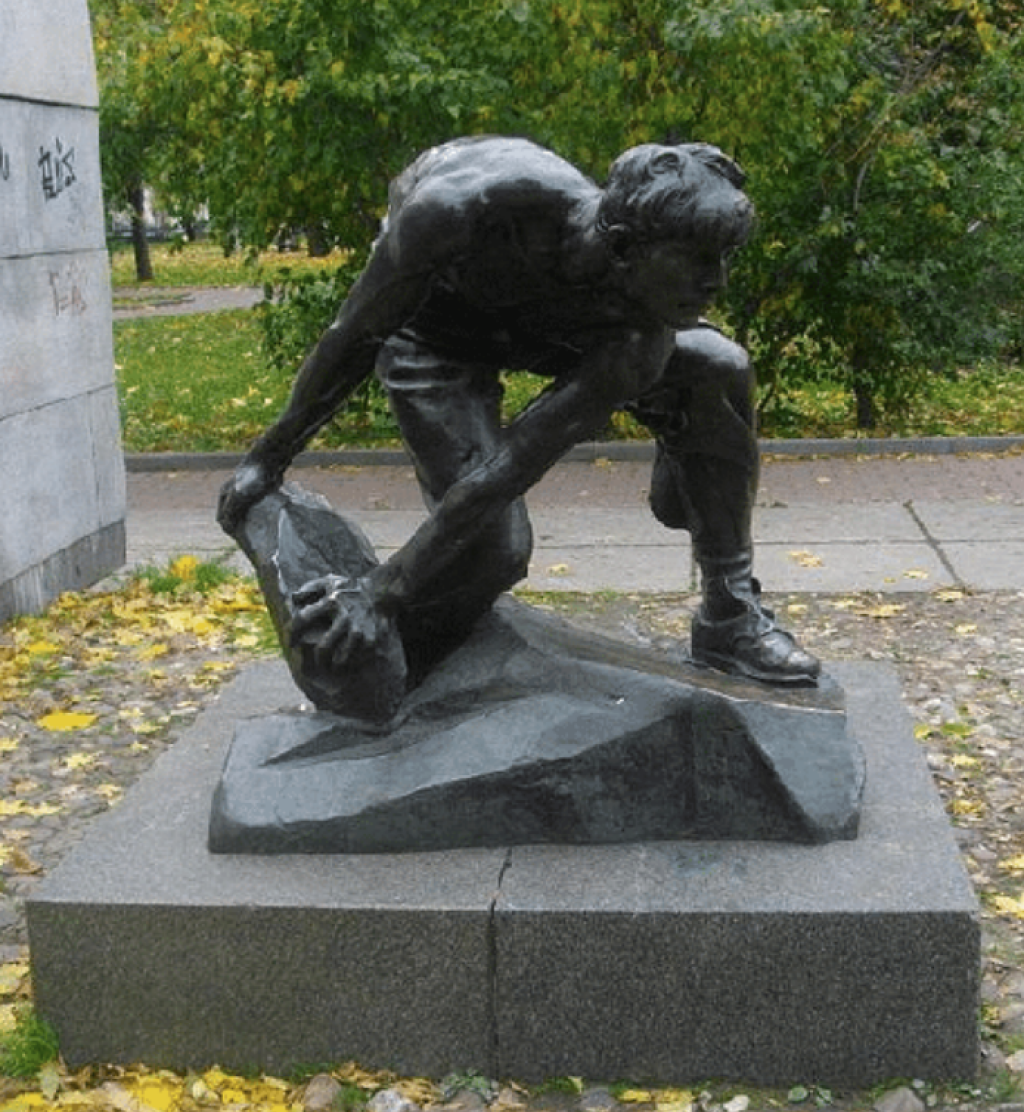

Vladimir was not the first famous Putin to come out of Leningrad. Mikhail Eliseevich Putin (1894–1969) came from the same district in Tver province as Vladimir’s grandparents, and in the 1920s became a celebrated “shock worker” in Leningrad’s Red Vyborzhets pipe factory. A shirtless Mikhail served as the model for I.D. Shadr’s 1927 sculpture “Cobblestone: Weapon of the Proletariat” (seen in the image accompanying this post) and supposedly launched the first “socialist competition” in 1929. One example of Mikhail’s eminence is that, in 1934, he chaired the funeral of the slain Leningrad party chief Sergei Kirov. There followed a long career as a party agitprop leader: when he died in 1969, his obituary was on the front page of Pravda.

The standard story is that Vladimir was a man of humble origins, the son of a worker’s family who lived in a communal apartment and experienced upward social mobility thanks to his entry to Leningrad State University. This image of Putin as a man of the people was carefully crafted by the Kremlin’s PR machine after his accession to the presidency on 31 December 1999, with the release of an authorized biography, First Person, and “The Unknown Putin,” a moving RTR television documentary about his childhood years.

That image is called into question if it is indeed true that he received assistance or inspiration in his career from his status as part of the extended family of a leading Communist official.

Chris Monday was a graduate student in St. Petersburg from 1997-2004 when he first heard reports about possible family connections between Mikhail and Vladimir. After exhaustive archival research and interviews with surviving members of the Putin clan (rod), he published his findings in Journal of Soviet and Post-Soviet Politics and Societies (8:1 2022), and a shorter version in History News Network in January 2023.

Monday argues that there were only a handful of families with the name "Putin" in mid-century Leningrad, all of them, it seems, coming from the Pominovo district in Tver province. He posits that the parents of Vladimir would have known Mikhail and may have reached out to him for help. He suggests that Mikhail may have lodged with Vladimir’s grandfather, Spiridon, on Gorokhovo street from 1906, and that Mikhail may have helped Vladimir’s mother when she moved to Leningrad in 1941—while grandfather Spiridon was working as a cook for Stalin in Moscow.

There is another coincidence in the two men’s biographies. As is well known, Vladimir was a passionate martial arts enthusiast, joining a sambo club in 1965. Before he became a star worker, Mikhail was a champion wrester, his involvement with the martial arts community continuing throughout his career.

Monday argues that “the existence of a kin relationship between the two men would help explain certain puzzles linked to Putin’s biography”—such as Vladimir’s enrollment in Leningrad State University and recruitment by the KGB: two elite institutions with high barriers to entry. Mikhail died in 1969, before Vladimir entered the university (1970) and joined the KGB (1975). But Monday suggests that “the shadow of Mikhail would continue to give Putin a leg up.” Soviet ideology officially endorsed and promoted the idea of “worker dynasties,” and information about an applicant’s family background would have been gathered.

Philip Short, the author of a new biography of Putin, exhaustively researched his childhood in Leningrad. Short is skeptical of the Mikhail connection, pointing to the absence of hard evidence. Putin’s family lived in one room in a communal apartment, hardly a sign of communist privilege. However, it is hard to explain why Putin was accepted to such a competitive university program. Short reports that there were 40 applicants for one place in the international law faculty, and that 90 of the 100 students accepted in 1970 had already completed their military service, which Putin had not. By his own account, Putin was not an exceptional student in high school, and due to some behavioral issues he was three years late joining the Pioneers and the Komsomol. We are left with the argument that it was his judo prowess which secured him entry to the law faculty.

The details of Putin’s personal history are now a taboo subject, and we may never know the true particulars of his family background. Monday reports that “all the parish registers down to the sixteenth century that mention Putin are off limits to researchers.”

If Vladimir Putin did indeed come from a family with ties to the Soviet nomenklatura, that would illuminate the role of personal connections in an allegedly egalitarian and meritocratic society. It also resonates with recent research emphasizing the continuities in Russia’s ruling elite across the 1917 and 1991 regime transitions, due to the persistence of networks of favors and "human capital" across the generations. Such research includes Maria Snegovaya’s work on the nomenklatura ties of the Putin elite and Tomila Lankina’s book, The Estate Origins of Democracy in Russia. It has long been recognized that Communist China’s ruling elite is deeply shaped by family ties and patronage.

It also conforms to the broader sociological pattern of how urban migration works, in Russia and elsewhere. In Tsarist Russia, it was common for peasants moving to the city to connect with people from their home district who could provide accommodation and help finding work. Such self-help communities were called zemliachestva, similar to the German term Landsmann. (There is no equivalent word in English.) These communities were often based on ethnic minorities, but were also formed by ethnic Russians. Such networks persisted into the Soviet and post-Soviet eras—see, for example, this article on their role in contemporary Moscow. Such behavior is familiar to students of the role of ethnicity in economic modernization in the developing world.

Inna Leykin has shown that researching family genealogy is a popular pastime in Russia, as it is in the West. But what does the possibility of a connection with Mikhail Putin mean for our understanding of the dynamics of the Putin regime?

Probably not very much. Ordinary Russians are likely to be indifferent to the argument that their leader had some family connections with the Soviet nomenklatura. Popular support for Putin was not dented by revelations about his personal wealth, his philandering, or even his launching of a brutal war against Ukraine.

His relationship with Mikhail Putin, wherever the truth lies, will remain a footnote to history. And only academics are interested in footnotes. But given Putin’s pivotal significance in Russian history, it is important to continue the work of trying to better understand the mechanics of his rapid and unexpected rise to power.