This is Part II in a two-part series. Part I may be found here.

A review of Dear Comrades!, Dir. Andrei Konchalovsky, 2020. 121 mins. Available on Hulu.

Peter Rutland is a professor of government at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut.

The 83-year-old Konchalovsky has a long and distinguished career. He served as a writer for Andrei Tarkovsky’s masterpiece Andrei Rublev (1966), and directed films such as Siberiade (1979). He moved to Hollywood in 1980, where he had a moderately successful career directing movies including Runaway Train (1985) and Tango and Cash (1989). His Holocaust drama Paradise (2016) was shortlisted for an Academy Award.

Konchalovsky comes from an elite family. His father, Sergei Mikhalkov, wrote the lyrics for the Soviet national anthem adopted in 1944, for its revised version in 1977, and for the new Russian anthem in 2000. Konchalovsky’s brother, Nikita Mikhalkov, is also a film director (and avid Putin supporter), who won an Oscar for Burnt by the Sun (1995), a film that looks back at Stalin-era repression.

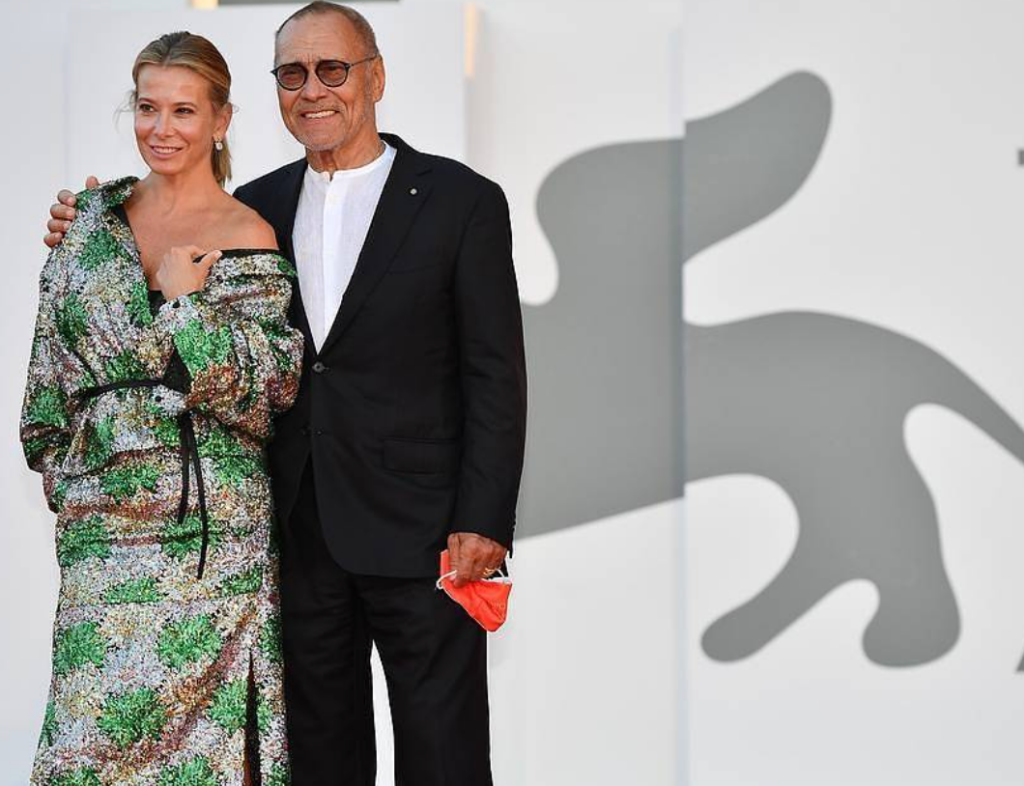

Keeping things in the family, the lead actress in Dear Comrades!, Yulia Vysotskaya, happens to be Konchalovsky’s (fifth) wife. By coincidence, she herself was born in Novocherkassk. Her family never mentioned the events of 1962 — they were too frightened.

The film conveys the main events of the tragedy more or less accurately. Vysotskaya’s character, Lyuda, is an official on the city’s party committee. An enthusiastic Stalinist, she calls for harsh measures against the strikers. The two main narrative threads of the film are Lyuda’s search for her daughter, who goes missing during the protests, and the steps being taken by the ruling powers to reestablish control.

The film does a good job capturing the gap between the wooden language of party officials and the grim reality of daily life for ordinary citizens. The episodes where the Presidium delegation arrives and starts barking orders to seal the city to prevent the news from spreading are reminiscent of similar scenes in HBO’s Chernobyl. In the 24 years between 1962 and 1986, the standard operating procedures of the Soviet state don’t seem to have changed very much.

Curiously, this is a film about a workers’ revolt in which we never hear from the workers themselves or get any insights into their lives. They are portrayed only in crowd scenes — jostling for food in a store or throwing stones at the party headquarters. The final scene shows couples sheepishly dancing on the town square in a hastily-arranged concert, on asphalt that was freshly laid to cover up the bloodstains.

Renditions of historical protest movements on the screen can be dull agitprop (Peterloo), lively entertainment (Les Miserables), or electrifying works of art (The Battle for Algiers). All films in this genre at least make at least some effort to convey the feelings and motives of the people driven to rebel.

But Dear Comrades! is told almost entirely from the point of view of the ruling elite. The two main characters are a Stalinist party secretary, Lyuda, and a KGB officer, Viktor, who ends up helping her (and who is the closest thing to a hero in the film). The various officials repeatedly refer to the protesters as “hooligans,” and by the end of the film that’s probably how the audience sees them, too. The brutal suppression of the protests is presented as a moral dilemma and a crisis of conscience for the elite. Blame is heaped on the Communist Party and the KGB, while the army comes out looking rather clean. These narrative choices all presumably suit Konchalovsky’s conservative-nationalist and pro-Putin agenda.

This approach fits the longstanding pattern of Russia’s political and cultural elites looking down on the people as ignorant and dangerous. In an interview years later, one of the participants, Valentina Vodyanitskaya — who was sentenced to 13 years in jail — said that director Kurochkin treated the workers as “bydlo” (cattle).

As a young man in the early 1960s, Konchalovsky himself had socialized with some of the advisors to Yurii Andropov, then-head of the KGB. In a 2011 article, Konchalovsky approvingly quoted the tsarist minister Petr Stolypin: “In Russia liberal reforms can only be possible if the regime first clamps down, because for a Russian any relaxation in the system represents weakness.” In an interview, Konchalovsky said that under Stalin “greed was controlled by the state” and mentioned that he sees the film as a tribute to the fact that “A lot of communists were very pure, very idealistic.” In a 2014 interview, Konchalovsky said that Russians have a “medieval mentality,” and Stalin erred because “he believed that politics could change mentality.” Moreover “the idea that freedom brings prosperity is an absolute mistake.”

The elite framing of the worker unrest is underlined by Konchalovsky’s artistic choices. The film was shot in black and white, in a 4:3 aspect ratio, to evoke the classic Soviet movies of that era — and also, one suspects, to emulate Alfonso Cuarón’s Oscar-winning Roma and Paweł Pawlikowski’s Cold War and Ida. Vysotskaya’s self-indulgent and mannered portrayal of Lyuda stands in a long tradition of Russian over-acting. She monopolizes the screen, constantly inviting viewers to marvel at what a great actress she is.

Dear Comrades! won a special jury prize at the Venice film festival in September 2020. In interviews in Venice, Konchalovsky explained that cinema is an art form in which the facts don’t matter; what is important is to get people to believe in the characters: to laugh, cry or feel horror. “The audience does not have to think anything.” He said that his templates were the Greek tragedies of Medea and Antigone. A one-hour promotional video follows Konchalovsky and Vysotskaya as they cavort through luxury locations in Venice between interviews. At one point Vysotskaya goes down on her knees before Konchalovsky and bows to him as a “master.” These scenes are surreal when juxtaposed with the grim lives of the Russian workers who are the pretext of the film.

The film's dubious politics is underlined by the fact that it was financed by Alisher Usmanov, whose name is prominently displayed as producer in the opening credits. Usmanov, a billionaire worth $21 billion, is under threat of US and EU sanctions because of his close ties to the Kremlin.

This is not the first time that the Novocherkassk protests have been dramatized onscreen. In 2012, Konstantin Khudyakov directed a TV series, “Once upon a time in Rostov,” based on the real-life story of a gang of bank robbers in nearby Rostov. The first two episodes are devoted to the revolt in Novocherkassk. They give, at least for this viewer, a more realistic portrayal of what happened than Dear Comrades!

Of course, this is also not the first time that historical films have been enmeshed in contemporary political debates. On one side, we have films that critique the Putin regime like Andrei Zygantsev’s Leviathan. On the other side, we have patriotic blockbusters aimed at fueling nostalgia for tsarist law and order, such as Nikita Mikhalokov’s Barber of Siberia (1998). At first glance, Dear Comrades! appears to belong to the first category, speaking truth to power. Yet arguably, it actually belongs to the second category, since it cultivates a sense of resignation about the way Russia works.

One recent parallel is the 2018 film Story of an Appointment, based on a real 1866 incident in which Lev Tolstoy served (unsuccessfully) as the advocate for a soldier sentenced to death for striking an officer. The film’s director, Avdotya Smirnova, is the wife of former privatization tsar Anatolii Chubais. The film triggered a vigorous debate because it portrayed the intelligentsia in a less-than-favorable light, and gave the impression that between a dissolute people and brutal state there was little hope for positive social change.

******

Worker unrest was the Achilles Heel of the Soviet system. Poland’s Solidarity trade union brought about the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe and then the end of the Soviet Union itself. Gorbachev was willing to send in the army to suppress nationalist dissent in the non-Russian republics of Georgia, Azerbaijan and the Baltics in 1989-91, but refused to use force to end the miners’ strikes that swept across Russia in July 1989.

Today, Russia’s rulers peer out at society from the “Kremlin towers” and are mortally afraid that the people will rise up and tear down their system of rule. This has actually happened twice in the past century — in 1917 and 1991 — so they cannot take their wealth and power for granted. On January 23, more than 100,000 people took to the streets in over 100 Russian cities to protest the arrest of Aleksei Navalny on his return from Berlin. The dilemma facing Russia’s rulers in Novocherkassk in 1962 — to shoot, or not to shoot — remains as relevant as ever.

Vladimir Putin is a product of the Soviet era. He has drawn some important lessons from the collapse of the Soviet Union. Let us hope that he learned that a state that relies on force alone is doomed to collapse.