This is the seventh entry of Russia’s Alien Nations: The Secret Identities of Post-Socialism, an ongoing feature on All the Russias. It can also be found at russiasaliennations.org. You can also find all the previous entries here.

When an alien space ship comes aground in the 2009 animated feature Monsters vs. Aliens, a reporter who sounds remarkably like Tom Brokaw announces, “Once again, a UFO has landed in America, the only country UFOs ever seem to land in.” This is one of those cartoon moments of self-aware humor clearly directed at the parents in the audience, but, as the saying goes, it’s funny because it’s true.

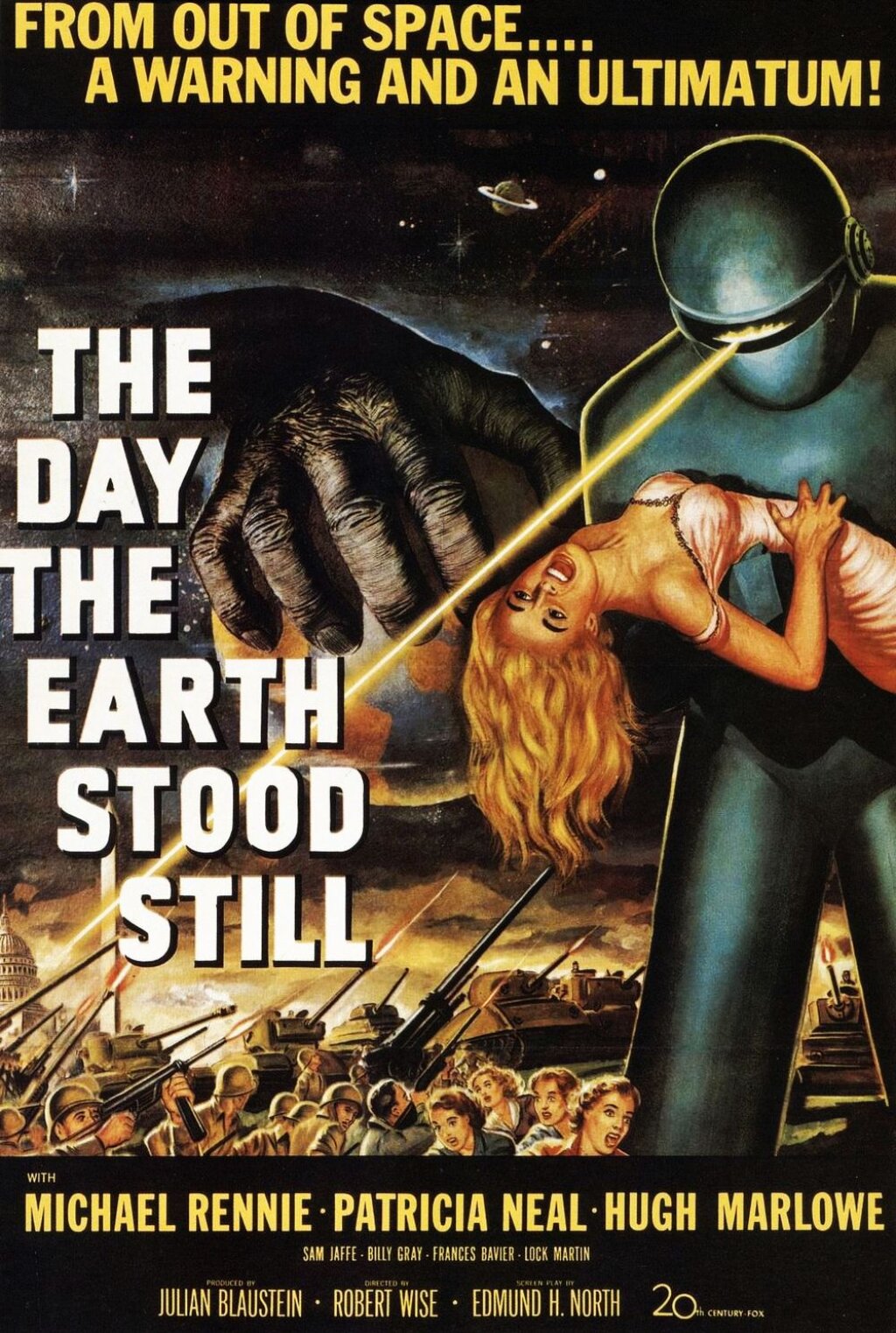

In modern science fiction, the United States is a prime target for alien visitation. Witness the classic 1951 film The Day the Earth Stood Still, where a humanoid extraterrestrial named Klaatu lands in Washington DC and nearly dies after being shot due to a misunderstanding. The world ends up on the brink of annihilation at the hands of Klaatu’s robot, only to be averted at the last minute through the repetition of Klaatu’s mysterious command “Klaatu barada nikto". By sheer coincidence, that last word is the Russian for “nobody,” a noun that would be appropriate for a depiction of Russia’s role in such tales of first contact: nobody from outer space bothers to go there.

Whether or not aliens intend to colonize the earth, when it comes to first contact with aliens, America has colonized the international imagination. In 2000, the Russian dramatist Evgeny Grishkovets published a novella in monologue form about his relationship with the United States, a country he had never visited. Entitled “A…..a”, as if the country’s name were a taboo, the novella frames the question in decidedly science fictional terms:

Isn’t it strange that in all, or rather, in most fantastic films and novels, if aliens come to Earth, they always arrive in the United States. And it’s not only because most of the films and books are made in America. It’s just hard to imagine that aliens would land anywhere else.

Grishkovets rejects a range of possible alternative landing sites: China, Hungary, Belgium. Why bother? In any case, the Americans will be right there to figure things out, so the aliens shouldn’t waste their time. And as for Russia: "Coming to us is either too early, or too late. It could make too unpredictable and incorrect an impression, and the consequences are best left unimagined. “ The United States simply makes sense. Grishkovets concludes: “If I were an an alien, I would land only there.”

For the most part, the history of Russian science fiction supports Grishkovets’s premise. That this was the case during Soviet times should come as no surprise: why would a country whose government is so cautious (and intermittently paranoid) about its citizens’ contact with real, existing foreigners from the dystopian hellscape of late capitalism be comfortable with stories about space aliens’ adventures in the USSR? Such an alien viewpoint could be didactic (as it was in Alexander Bogdanov’s 1912 Engineer Menni, about a socialist Martian from his previous novel Red Star (1908) visiting our world), But the danger of satire was also quite clear.

Thus Russian-language stories and films about alien visitors to the USSR were few and far between. The most famous tales of alien visitation and its aftermath (such as the Strugatsky Brothers’ Roadside Picnic and Tarkovsky’s adaptation, Stalker) set the action in other countries. Aliens do occasionally come to Russia in Kir Bulychev’s series The Adventures of Alisa (including his most famous scoundrels, Krys and Vesel’chak U), but only once do they make it to the twentieth century; the rest of the adventures take place at the end of the 21st (Per Asper ad Astra, the 1981 film written by Bulychev, takes place one century after that). In their novella “The Visitors,” the Strugatsky brothers set their story of mysterious aliens in the context of an archaeological expedition in Tajikistan. Whether remote in time or in space, the safest place for the story of alien visitors to the Soviet Union was somewhere that minimized the social and political context (as in the 1978 short psychedelic cartoon Contact (Vladimir Tarasov), which depicts the encounter between a Bohemian painter and a shape-shifting alien in a vague, bucolic setting).

Of course, not everyone chose the safe route.

Next: A Hothouse Flower in a Communal Apartment