This week, All the Russias is pleased to feature thesis profiles from graduating M.A. students in the Department of Russian and Slavic Studies. The is the second post in the series; the first may be found here.

Scout Mills is a rising doctoral student in the Department of Slavic Languages at Columbia University. She receives her M.A. in Russian and Slavic Studies from NYU this May.

On March 14, The Eurovision Song Contest officially began with its first semifinal in Tel Aviv. Established in postwar Europe in 1956, Eurovision has become a symbol of bridge-building and unity despite elements of geopolitical soft power that have come to infiltrate the fantasy of an apolitical song contest. William Lee Adams, founder of Eurovision Song Contest fan website Wiwibloggs, views the contest as an opportunity to celebrate diversity and a dream of unity despite growing political rifts and rampant radicalism. “The cracks seem to run deep,” he writes. “But at Eurovision […] I regularly see a vision of Europe where fans across the Continent, artists and their entourages are more connected than ever.” But why should we care about Eurovision, a spectacle of glitter and camp that thumbs its nose at political protest? In order to argue for the significance of the contest, my thesis, "Bedazzling Russianness in Three Minutes: Eurovision and the Russian Cultural Narrative Abroad," analyzes Russia’s presence in Eurovision as a country whose recent political developments have severely damaged its reputation in Europe.

Since Russia's annexation of the Crimean Peninsula in 2014, Eurovision audiences have booed Russian performers. In turn, Russian commentators have consistently blamed their country's Eurovision losses on political voting. However, the rift between Russia and Europe has hardly hindered Russia’s participation in the contest: indeed, it has submitted a new entry every year since 2014 despite being banned from the contest in 2017. I explain Russia's continued participation through an analysis of what I call its "Eurovision narrative," exploring how it managed to condense and transform its national identity for European audiences. Other questions I investigated included how the resulting narrative tends to be received by Eurovision fans, both Russian and non-, and how Russia’s narrative interacts with fans’ reactions. And, perhaps most importantly, I sought to understand the significance of Russia’s narrative and its very construction.

My thesis argues that making sense of conflicting narratives about Russia’s place in Eurovision from Russian and non-Russian media, Eurovision fans, and the larger voting public is key to understanding Russia’s Eurovision presence. Collectively, this presence suggests that Russia creates a narrative wherein it is both champion and underdog. Because Russia is faced with the task of presenting itself in a space where politics are officially outlawed, the country is forced to present an apolitical narrative. However, even when Eurovision’s official policy is to remain apolitical, presenting national identity onstage naturally invites political performance.

Russia’s Eurovision presence is a condensed expression of Russian national identity that not only reveals how Russian state-owned media chooses to curate identity for an international audience, but also draws on a larger trend of adopting Westernized media in order to portray Russia as a competent, non-“backward” country. The subsequent narrative of victimhood when Eurovision doesn’t work in Russia’s favor is also reflective of older inferiority complexes and the false dichotomy between West and East that is reinforced by both players.

For Eastern European countries Eurovision is a competition fought on a Western battleground, as international juries are keen to select songs they deem “radio-friendly,” meaning similar to Western European pop. This Western-centric perspective is precisely what allows the Russian narrative of inferiority to function. Russia’s attempts to produce Western-style pop songs often succeed with viewers, thus validating their ability to play the game; at the same time, Russia's submissions are not always successful with juries, who represent the "experts" in European pop music. Russia’s insistence on playing by Eurovision rules is the strongest part of its narrative. In order to escape a stereotypical narrative of "Russianness," the country abandons obvious displays of nationalism. Indeed, even as they strive to win the contest while displaying a version of “Russianness,” they must avoid either falling into the stereotype of the aggressor or of an aggrieved victim of a “Russophobia” that dominates Eurovision discourse.

Yet Eurovision represents more than the chance to condense and sell cultural narratives, for Russia as well as other nations. It is also a sphere wherein fans and nations look to utopian ideals in order to find a place in an imagined Europe. The particularity of Russia’s Eurovision narrative, I show, is that it originates in a country that regularly comes close to winning while remaining the target of political protest from fans. Russia must consistently work against its role as an aggressor — and in recent years, it has taken an aggressive approach to doing so. The immense effort that Russia invests in its Eurovision entries and their recent hosting of the Olympics and the World Cup clearly show that they are a country with their “eyes on the prize.” Currently a favorite according to the bookmakers, Russia could easily win Eurovision 2019, thus earning the right to host — and therefore continue to battle stereotypes through public presentation — in 2020.

Though Russia’s role within Eurovision can be both frustrating (to viewers) and frustrated (from its own perspective), the country remains an integral participant in the contest. Indeed, Eurovision may be one of the only spaces where Russian artists and fans can interact with artists and fans from other nations in a positive, constructive way. The fact that Russia has created a narrative of “strongman victim” does not inherently suggest that other countries would not do the same if they were in a similar position. Russia’s narrative may very well reveal the strong presence of an “East versus West” dichotomy in the contest wherein Russia is a scapegoat for fans’ political protest. But if Eurovision needs scandal and tension to function, the choice of Russia as a target of protest is somewhat arbitrary. If Russia was not the focus of fans’ ire, another nation might be so in its place.

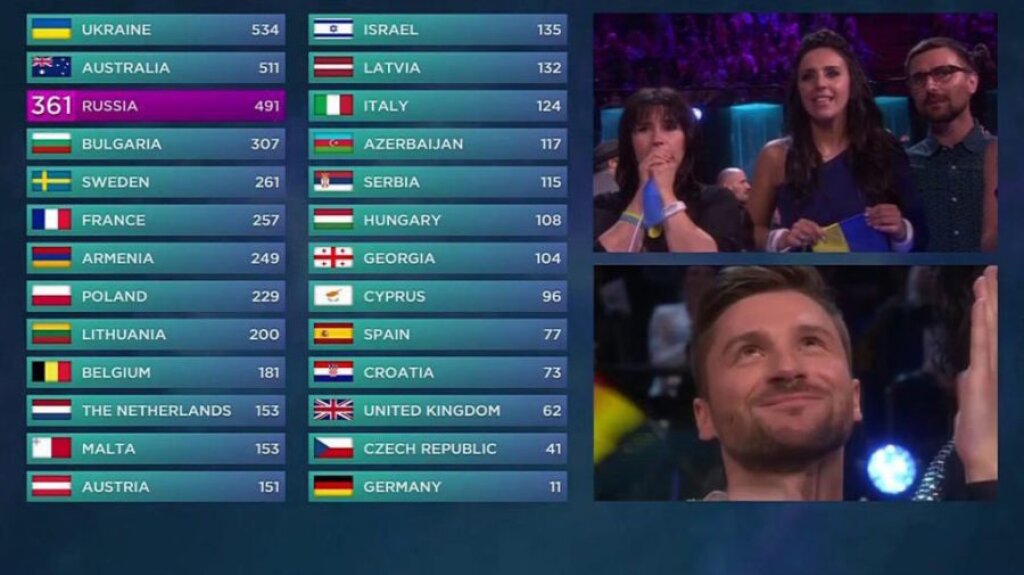

In 2016, each of Russia and Ukraine’s twelve televote points went to the other country. This outcome could have proceeded from a multitude of factors, but also tells us that political allegiances are not the only determiners of Eurovision outcomes. Genuine appreciation of a song, or even a country and its culture, cannot be ignored as a contributing factor to Eurovision victory or defeat, which suggests that fans wishing to ban Russia or punish Ukraine for its politics are not in the majority. The implications of my thesis are clear: Eurovision is a cultural artifact that lays bare the intersections of national identity and popular culture. In Russia’s case, Eurovision is a chance to belong to a larger European public, even if it struggles to overcome political narratives imposed by contest fans. Ultimately, however, if anything prevents Russia from fully belonging to the dream of a united Europe, it is the nation's own, self-constructed narrative.