We at the Jordan Center stand with all the people of Ukraine, Russia, and the rest of the world who oppose the Russian invasion of Ukraine. See our statement here.

Natalia Vygovskaia, a PhD candidate in Slavic Studies at Brown University. She researches medical ethics in doctors' narratives in late Imperial Russia.

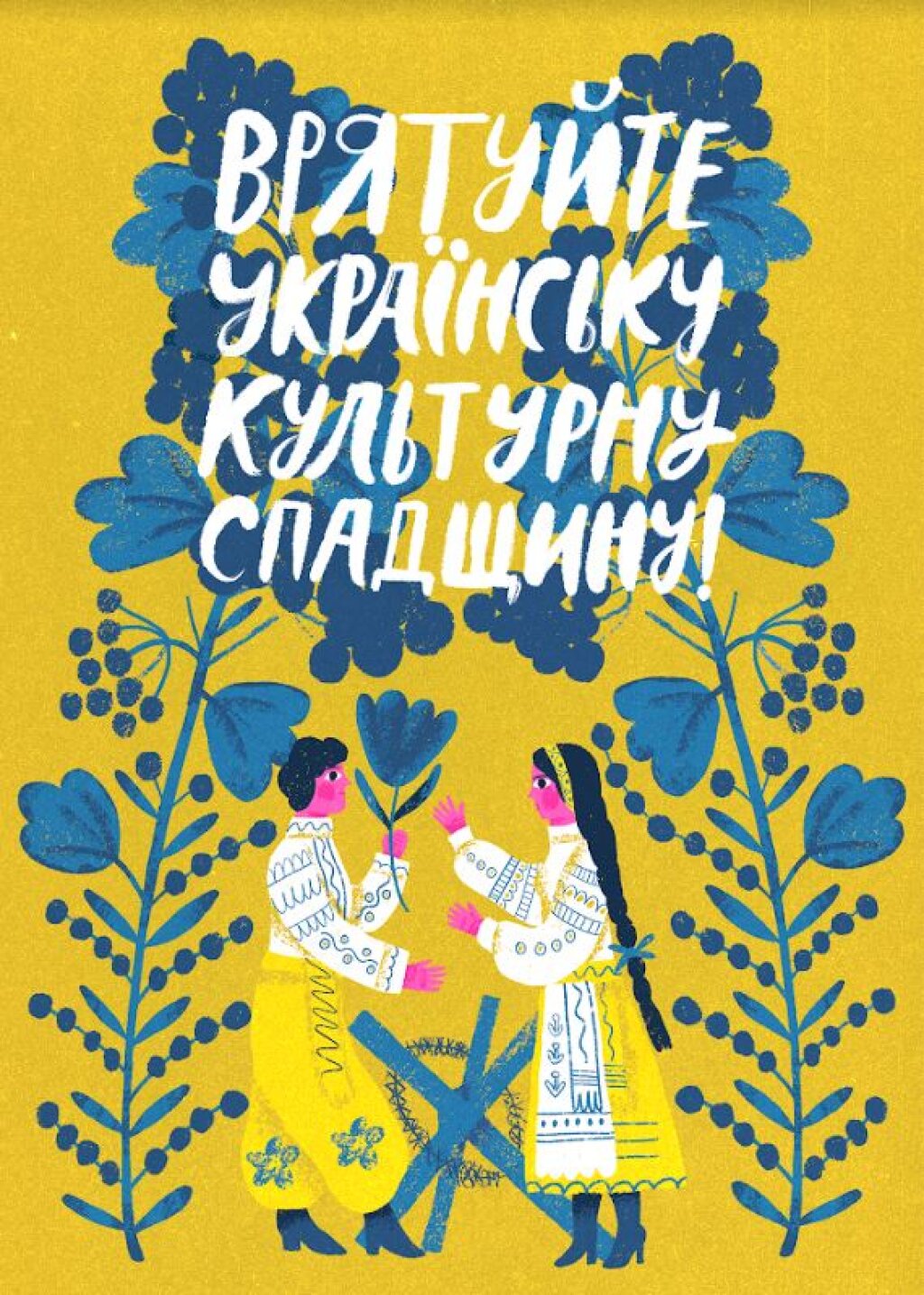

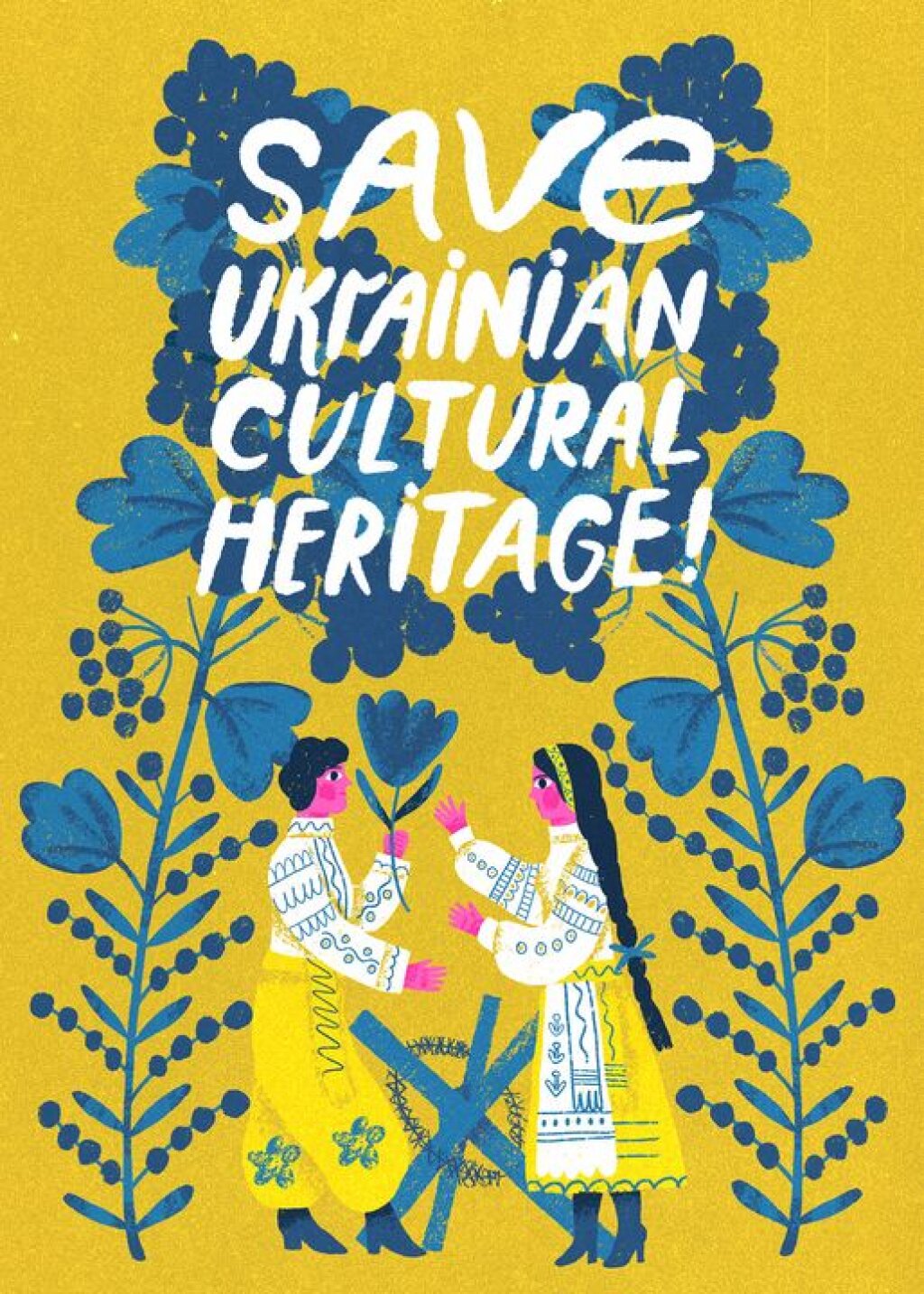

I quickly check my Slack messages. One of them resends in the attachment a beautiful picture of a young man, giving a tulip to a girl under the arch of blue flowers. The painting “Save Ukrainian Cultural Heritage!” was created by a Ukrainian artist Daria Filippova with inspiration from Maria Primachenko as a token of gratitude. The artist thanked the group of more than 1,300 people for the job they have been doing to preserve digital archives of Ukrainian cultural institutions: at museums, universities, libraries, research institutes.

Quinn Dombrowski (Stanford University), Anna E. Kijas (Tufts University), and Sebastian Majstorovic (Austrian Centre for Digital Humanities and Cultural Heritage) started the project in early March, and since then hundreds of volunteers have joined the team.

All of us, librarians, archivists, researchers, and programmers, want to help and can do that in different ways. What we share in common is our commitment to saving culture from barbarian destruction and our understanding that it is an urgent matter.

Volunteers at Sucho.org come from all parts of the world and use Slack as their main communication channel. There are numerous slack groups – any new member can choose one, depending on their interest, and ask a question. If it is not clear whom to contact, it is ok to ask a question in #general, and then you will be redirected to someone who might help with the inquiry.

I do quality control because I can read in Ukrainian and Russian. Native speakers are in high demand because they are faster to spot any problems with the archived copy. Normally, I browse pages and compare two versions: the archived one with the original one, and check if they match. I write notes in QA column of the google sheet to let the archivist know if there is something to correct, and mark the status of QA as ‘’checked’’ or ‘’incomplete.’’ There are lots of volunteers working in the same doc twenty-four hours a day. Some of them put their kids to sleep and get down to writing a code, while some take a lunch break and submit a website for preservation. This planetary collective effort gives me hope that there is something we can do and resist the totality of dehumanization.

Each time I open a google sheet with the sites that need quality control check, I see the ones that are down, infected with malware, and not accessible anymore. What we are doing in the virtual cloud depends on what happens there, on a battleground. There is a list of cities and towns currently under attack, and it is getting longer. The archivists first go to high-risk collections, trying hard to get ahead of time to create copies. Each hour, under shelling, the flickering lights of Ukrainian culture risk disappearing into the darkness of oblivion.

I click the link that allows me to download the scan of Glagolicheskie listki from the site of the Institute of History of Ukraine in Kyiv – the oldest Slavonic manuscript in the oldest known Slavic alphabet. I cannot imagine that the common past that children from both countries learn about at school is being destroyed at this very moment.

Browsing web pages, I glimpse the life of scholars and librarians, teachers, and craftsmen, who opened exhibitions, recorded workshops, organized conferences not so long time ago: shining eyes and smiling faces of people who love their work and, sadly, are being forced to leave their homes.

It breaks my heart to see that the Russian invasion kills culture. It fills me with anger and fury when every time I read our website list, I find another link to the page that does not open – it means that the server is down, it means that people, who were trying to protect and maintain it, are gone, it proves that the war is there and its devilish shadow is crawling onto and erasing what used to be personal stories and cherished memory.

Pianists play their goodbye pieces to the sounds of air raids; city residents cover statues and monuments to protect them from bombs; poets write stanzas about surviving in shelters; artists portray displaced families, leaving everything behind. Culture is trying to preserve itself, but this might not seem to be enough. It is a call for everyone to show solidarity and to help us save Ukrainian Cultural Heritage.