The Jordan Center stands with all the people of Ukraine, Russia, and the rest of the world who oppose the Russian invasion of Ukraine. See our statement here.

Dirk Uffelmann is professor of East and West Slavic Literatures at Justus Liebig University Giessen, Germany. A version of this article originally appeared in Russian Literature.

This is Part III in a three-part series. Part I may be found here and Part II here.

Khersonskii’s renunciation of Russian monolingualism peaked in August 2018 in an almost masochistic attack on his own Russophone past, which I quoted in this essay’s first installment. His “credo,” Khersonskii wrote, is that, in Odesa, it is necessary to “obstruct the Russian language gently, but oppose boorishness on the part of Russian cultural stars decisively.” In light of the poet’s attitudes toward Russophonia and Ukrainian as the state language of Ukraine, we may wonder if the linguistic performance he enacts on his Facebook page mirrors his ongoing alienation from Russia(n) and his efforts to learn, speak, and write more in Ukrainian.

For Khersonskii, code-switching within a single sentence or paragraph is rare. One instance occurs in his March 2014 announcement that he will lecture in Ukrainian as a demonstrative political performance. Far more frequent are double postings, meaning, posts where the content appears first in Russian, then in Ukrainian translation (by Galina Fleitman or Mar’iana Kiianovs’ka, or, increasingly over time, by the author himself). Some of Khersonskii’s posts explicitly justify his bilingual blogging as part of advancing the “Ukranian national idea,” which he considers “existential.”

Khersonskii’s bilingual Facebook posts are mostly consecutive self-translations of older, generally apolitical poems from his own corpus. He quotes frequently from the Ukrainian translation of his best-known book, Rodynnyi arkhiv, ahead of its 2016 publication in Ukrainian. Consecutive self-translations of politicized poems soon followed, including “Posmertno—I.B.” [“Posthumously—To I.B.”]), Khersonskii’s poetic reaction to Iosif Brodskii’s notorious paean to Russian imperialism, the 1991 poem “On the Independence of Ukraine.” “I live on a broken piece of Empire, better not touch it,” wrote Khersonskii, “The double-headed eagle will break his talon.” This bilingual blog entry contrasts with the monolingual version of the poem published in Stalina ne bulo.

Some of Khersonskii’s bilingual blog entries are simultaneous self-translations of political and metalinguistic comments triggered by his burgeoning support for the Ukrainian language. In August 2016, for instance, he wrote that “many of my readers have already forgotten (and many more have never known)” that thanks to “my seemingly totally pro-Ukrainian Russophone colleagues,” he was now being coded as an “enemy of the Russian language.” The “patriotic literary public” of Russia, Khersonskii reports, took up this “Ukrainian Russophone bullshit” and spent several weeks “trashing” him online.

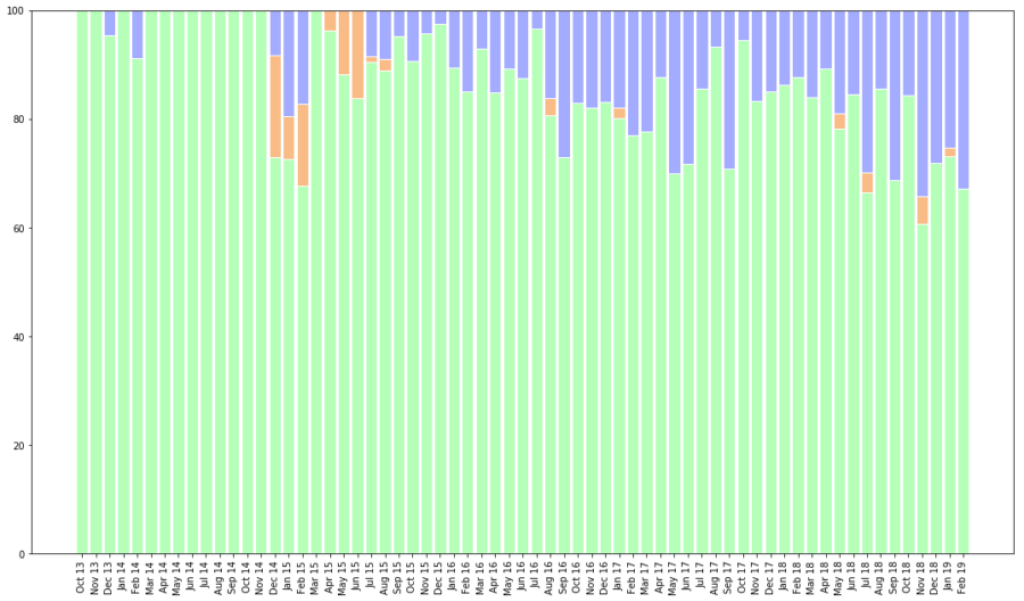

Up to early 2019, Khersonskii’s Facebook page exhibits not a continuous shift from Russian to Ukrainian, but a constant switching back and forth. A statistical comparison of his blog entries from October 2013 to February 2019 reveals a decreasing percentage of monolingual Russian posts (green), a brief peak in monolingual Ukrainian posts (orange) in the winter of 2014 and spring of 2015, followed by a consistent rise in bilingual posts (blue):

Khersonskii’s linguistic choices sometimes correspond to his message, as when he pleads the case of Ukrainian in Ukrainian. At other times, this is not the case. In a trilingual Ukrainian-English-Russian post from July 2018, for example, Khersonskii attributes negative political connotations to the use of each of these languages, albeit for different reasons:

“[Ukrainian:] I just learned that, in Odesa, they can’t forgive me for sometimes writing in Ukrainian, allegedly for political and pragmatic (but not poetic!) reasons, since this [choice] makes me a servant of Ukrainian Nazism. / [English:] But, when I write in English, which I do from time to time, it is even worse because it makes me a slave of world capitalism. / [Russian:] And only writing in Russian frees me from any political influences and renders me independent of Nazism, capitalism, and the Russian World.

The final claim in this ironic post, “independence from the Russian World,” flies in the face of the poet’s arguments that language cannot be separated from either its speakers and the content of their utterances, in this case the Russian-language propaganda-esque invocation of “Russkiy mir.”

Khersonskii’s deliberate inconsistency in using—and arguing against—the Russian language may point to a tactic of counterviolence, enabled through code-switching. The poet suggests as much in a Ukrainian-language post from June 2017: “You ask why I am writing this in Ukrainian, whether I have forgotten Russian, if I feel like annoying the [Russians]? So I do. It’s my little linguistic revenge.”

Here, Khersonskii’s tongue-in-cheek mention of “revenge” fails to account for the far more deliberate and nuanced bilingual practice he enacts elsewhere. The predominance of posts containing Russian and Ukrainian versions of the same content suggests that these two languages can co-exist within the minds of a bilingual poet-blogger and his audience alike. When the poet polemically inserts inconsistencies in a bi- or multilingual post, these playfully undermine claims of Russian imperialism, but otherwise have little to do with any sort of “revenge.” Rather, Khersonskii uses self-translation and bilingual blogging as a form of conflict management. Couching even polemical zingers in irony and playful paradox, Khersonskii privileges linguistic performance over direct attack.

On the other hand, Khersonskii’s insistence on the obligation to master (and even love) Ukrainian as a state language, which he repeated following the adoption of a new Ukrainian language law in 2019, seems to discard flexibility in favor of a more radical stance. Here, he approaches the programmatic code-switching of other formerly Russophone Ukrainian writers like Vladimir Rafeenko, who have recently switched to Ukrainian exclusively.

For a professional writer to begin code-switching for the first time at age 66 is highly unusual. Even more remarkable is the shift in Khersonskii’s translation practice from B → A (foreign to native) to A → B (native to foreign). His formerly monolingual Facebook page, where the proportion of Russian-language content decreased by about a third by 2018-2019, also underwent a quite atypical code-switching. Rather than shifting from a “minor” language to a “hegemonic” one, as prevailing trends in self-translation studies would dictate, Khersonskii moved from Russian—dominant globally, online, and in Odesa at the time—to Ukrainian. He thus presents a seminal example of the rare strategy of anti-hegemonic code-switching.

Especially unusual is that Khersonskii’s digital code-switching defies the linguistic majority in his offline home, predominantly Russophone Odesa. Kersonskii’s code-switching thus targets a delocalized virtual audience, sending ideological signals toward the imagined community of a not only civically, but also “state-linguistically” Ukrainian nation. Taken together, Khersonskii’s posts thus imagine a future multilingual society that recognizes the civic obligation of understanding and speaking the single state language—Ukrainian. His own bilingualism, meanwhile, helps mitigate mounting language conflict by modeling flexibility within individual linguistic practice.