Frances Saddington has recently completed a PhD on the early Soviet picture book in the School of History at the University of East Anglia (Norwich, UK).

On a golden September afternoon in St. Petersburg, I found myself walking around the Leningradskii zoopark. I was in Russia to research early Soviet picture books, my brain was preoccupied with vivid images of Pioneer troops and racing locomotives, along with cannibal pirates and other fairy-tale characters. As I wandered past the farm animals and aviaries full of exotic birds, I let myself imagine what the zoo might have been like a century earlier, when the authors and illustrators I was studying might have visited.

I stopped short when I reached the big cats, realizing that a pride of bored, sleepy lions in a small, rusting cage looked just like an illustration in one of my favorite picture books. It was as though time had stood still and they had been here since 1928, waiting for me to turn up and take their photograph.

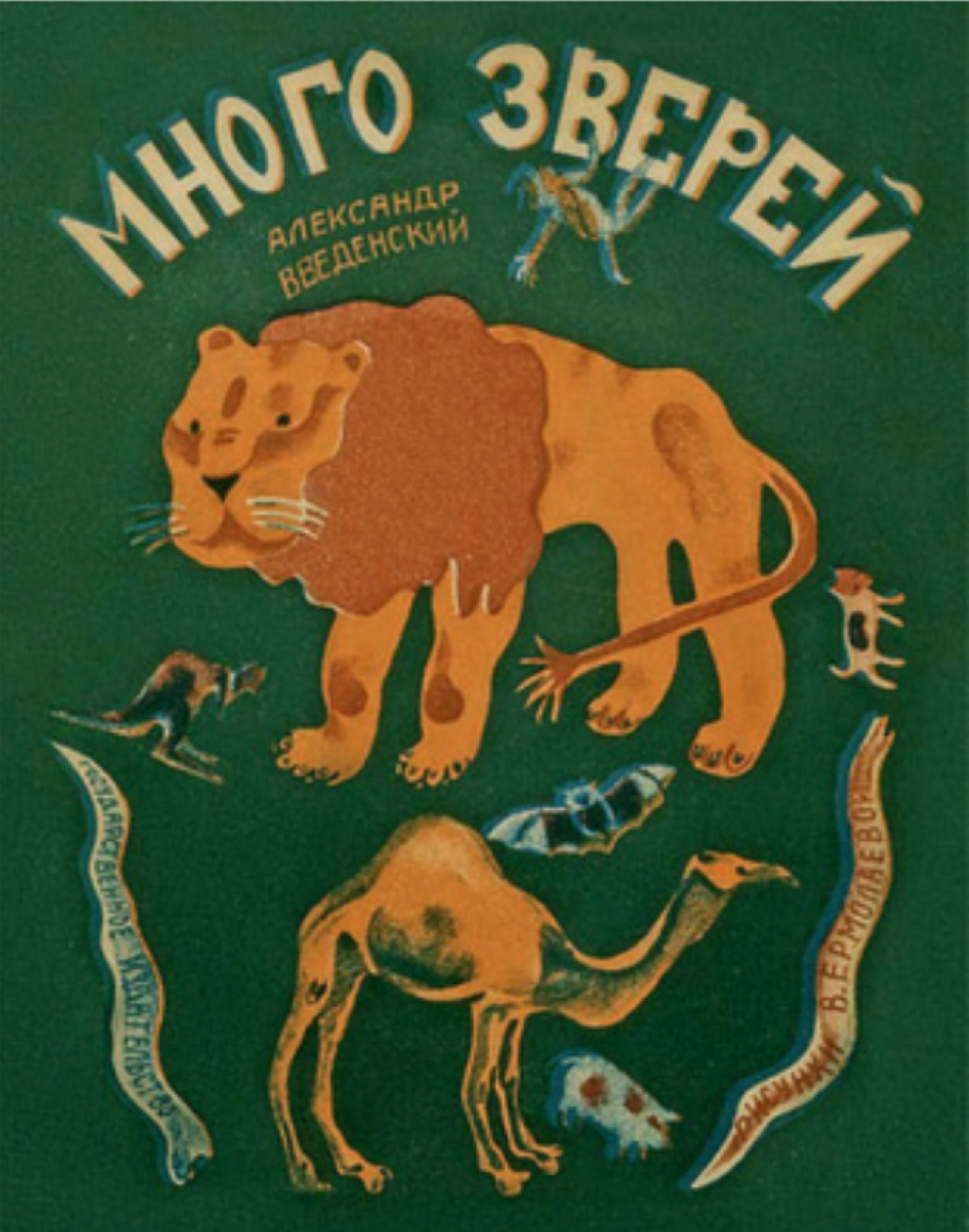

Many Beasts (Mnogo zverei) was written by poet Aleksandr Vvedenskii (1904-1941) and illustrated by the artist Vera Ermolaeva (1893-1937). An unusually subversive piece of verse for a children’s book, it told the tale of a trip to the zoo where foxes and seals greet the visitor cheerfully, but many of the other residents are deeply unhappy. Vvedenskii imagines that the camel would rather be in the desert, and an eagle sits on a stone all day feeling fed up because he is unable to fly. The parrots can talk, but they simply screech nonsense that nobody understands, while only the flies have any freedom, so they buzz around and mock the captive creatures.

Vvedenskii and Ermolaeva were important members of the Leningrad School of children’s authors and illustrators, who produced some of the most stylish picture books of the era. Ermolaeva was an incredibly gifted painter and illustrator, playing a key role in the early Soviet avant-garde. She was a leading organizer of the Segodniia (Today) collective, which, during the Civil War years, hand printed some of the first children’s picture books of the Soviet era. She also worked collecting advertising sign boards for the Petrograd city museum and was a close colleague of Kazimir Malevich (1879-1935) at the illustrious People’s School of Art in Vitebsk.

Ermolaeva’s work in Many Beasts is typical of her idiosyncratic, painterly approach to book illustration. She drew the animals as flat, slightly abstracted figures in earthy shades, which matched the unsettled tone of the poem. Her big cats are full of natural character, with the bored-looking lion and snarling puma fairly bristling on the page. The lion in the photograph that I took was bathed in the same golden light as the book illustration and stuck in a small, bare cage with several other animals. It had gone past the point of boredom and fallen fast asleep.

[gallery ids="6636,6635"]

A month after my excursion to the Leningradskii zoopark, I spent a chilly autumn day at the Moscow Zoo, a place equally full of picture book heritage. Boris Pasternak (1890-1960) must have been inspired by it when he wrote his poem The Menagerie (Zverinets), published as a picture book in 1928 with illustrations by Nikolai Kupreianov (1894-1933).

Pasternak’s zoo is a fascinating, almost mysterious place. The pond near the ticket kiosk shines silver in the wind and the roar of a growling puma echoes through the park. Bears hold conversations with visiting children, while the lioness paces up and down in meticulously measured steps behind the iron bars. A young Nile crocodile looks tiny, but will grow up to become far more terrible. The visitor is stunned by a fanned-out peacock’s tail, which looks like the night sky with fountains of falling stars.

On my own route around the park, I looked for tiny clues that would let my imagination recreate the zoo of the 1920s or early 1930s. Many things remain the same, including the huge pond near the entrance, the pony riding circle, and many of the enclosures in the zoo's "new territory," which was built in the late 1920s, across the road from the original site.

The most fascinating section of the new territory is Animal Island, a rocky edifice built to house large predators, surrounded by a moat to keep visitors safe. It is still inhabited by lions and other large creatures and retains its fascination for amateur zoologists of all ages. On the day I was there, grandmothers pushing prams stopped at the railings to let bundled-up toddlers peer at the big cats, who in turn shut their eyes disdainfully with no regard for the enthusiastic onlookers.

The structure was so innovative when it was constructed that it featured in a supplement to Iskorka (Sparkle), an illustrated magazine for pre-schoolers. Children were given printed shapes to cut out, which could then be glued together to make a three-dimensional model of the island. There were also cardboard animal templates, so that the model could be populated with lions, tigers, leopards, and bears, thus becoming a fully functional homemade toy.

[gallery ids="6633,6634"]

Animal Island has barely changed, but today it is dwarfed by the tall, faded, late-Soviet apartment blocks that dominate the skyline near the zoo. The city is bigger and busier than anyone could have imagined a hundred years ago, but children still love to gaze at the zoo animals, take a pony ride, and buy a balloon to take home. The lions are still haughty, the birds are still noisy, and it would be nice to think that somewhere in the constant stream of visitors there is an artist, sketching ideas for a new picture book that will still be read a hundred years from now.