This is the fifth installment of The Turkish Gambit portion of “Rereading Akunin” focusing on . For the introduction to the series, and subsequent installments, go here.

CHAPTER FIVE

In which the arrangement

of a harem is described

Yes, a harem. It’s an odd choice, devoting a significant chunk of a chapter, as well as the chapter’s subtitle, to harems, since, if I remember correctly, no one in the novel ever sets foot in one as the plot unfolds. But it is also fitting, since so much of this book engages in faux-Orientalist faux-ethnography, which makes sense in a work that is trying to reproduce the feel of a nineteenth-century war yarn.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about this excursion into harem life is Akunin’s decision to have it related by a source whose expertise is highly dubious. Fandorin himself was the guest of the Pasha, and comes off as more knowledgeable about Ottoman life than anyone else in the book. So, naturally, he is sidelined for most of the chapter, reduced to eye-rolling and muttered corrections noticed only by the reader.

The excuse for this chapter’s long digression is the surprise appearance of the second character from The Winter Queen to put in an appearance in the sequel: “Captain of the Grodno Hussars Regiment Count Zurov.” Ippolit Zurov, we recall, was the dissolute gambler who served as Vergil to Fandorin’s Dante when the latter unknowingly descended into the first circle of Azazel’s hell (Bezhetskaya’s soirée) and later saved Erast Petrovich's life when things got truly diabolical.

As a man of action, then Zurov proved to be a true friend to Fandorin. As a man of words, though, the only thing reliable about him is his propensity to get things wrong. Even now, he still calls Fandorin “Erasmus” (much to Varya’s confusion). And when he leads into his story, he makes a much more telling error:

“Don’t be shy, gentlemen, come closer. I’m relating my Scheherazade to my friend Erasmus here.”

“Odyssey,” Erast Petrovich corrected him in a low voice, retreating behind the back of Colonel Lukan.

“An Odyssey is what happens in Greece, but what happened to me was a genuine Scheherazade.” ”

As mistakes go, it’s a brilliant one. Zurov’s peregrinations and brushes with death could well be “Odyssey” material; after all, The Odyssey set the pattern for the male travel/adventure tale. But Zurov introduces a distinction that further underscores the Orientalist preoccupations of The Turkish Gambit while also invoking paradigms of female heroism, not to mention the power of self-conscious, intentional storytelling.

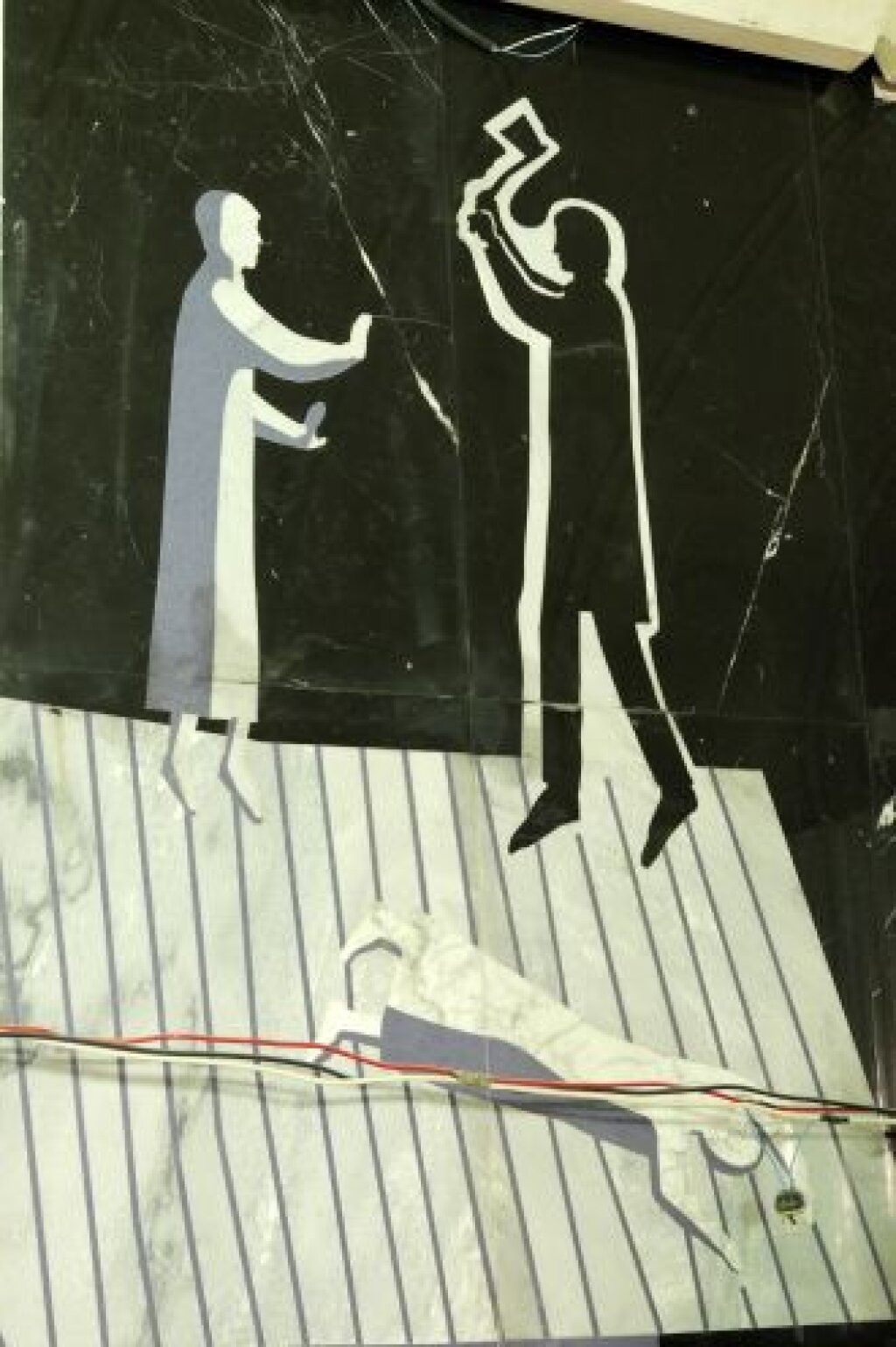

The very fact that it is Zurov himself who recounts his exploits puts him in the storytelling position occupied so famously by Scheherazade in the 1001 Nights, with the important distinct that Scherherazade told tales about others in order to save herself, while Zurov starts out bragging about his own feats of derring-do. This is a stereotypically gendered distinction, which may well be part of the point, emphasizing distinctions between both masculine and feminine heroism and masculine and feminine storytelling.

Storytelling, heroism, and imaginary geography are the binaries that distinguish Odysseus and Shcheherazade for the purposes of Zurov’s narration, at the same time that the two archetypal figures have something in common: their cleverness. Odysseus repeatedly talks his way out of danger, often through deceit, while Scheherazade’s entire narrative conceit is based on staving off imminent execution.

Zurov’s stories are all about his attempts to talk his way out of a difficult situation, usually brought on by his lack of funds. At one point he manages to get an audience with Hassan Hairulla, an important Turkish religious official (whom he mistakenly refers to as “the top Turkish priest, a bit like the Pop in Rome”). Hairulla interrupts Zurov’s attempts to speak with him by claiming, in French, that it is the hour of prayer, whereupon he prays aloud:

“He squatted down with his face toward Mecca and started repeating over and over: ‘Oh, great and all-powerful Allah, extend thy favor to thy faithful servant and let him live to see the vile infidels who are unfit to trample thy holy earth burning in hell.’ Very nice indeed. Since when did they start praying to Allah in French? Very well, I think, in that case I can introduce something new into the Orthodox canon. Hairulla turns toward me, feeling very pleased with himself now that he’s set the infidel in his place. ‘Give me the letter from your general,’ he says. ’Pardonnez-moi, éminence,’ I reply. ‘This is the very time set for us Russians to say mass. Won’t you pardon me for just a moment.’ Down I go, bang, onto my knees and start praying in the language of Corneille and Rocambole: ‘Lord of all blessings, delight thy sinful servant the boyar, that is, the chevalier Hippolyte, and let him rejoice in the sight of Muslim dogs roasting in the frying pan.’ In short, I caused complications in Russo-Turkish relations, which were already very far from straightforward.”

Zurov’s story is pure farce, the stuff of a picaresque novel. Nevertheless, the war hero Sobolev approves, although Captain Perepyolkin notes that Zurov was “ not very diplomatic”:

“I didn’t last too long as a diplomat,” Zurov sighed, then added thoughtfully, “Obviously, that’s not the way my path lies.”

Erast Petrovich snorted rather loudly.”

Diplomacy is neither Zurov’s path nor his genre. Indeed, his misnaming of his own story (“Scheherazade” for “Odyssey”) may be the most accurate thing he says, because it tells us not to expect accuracy. Zurov is a one-man Orientalizing machine. Immediately moving on to an encounter with a beautiful woman who turns out to be married to an important official (and whose status he once again misstates, once again causing Fandorin to correct him under his breath).

This, finally, leads to a discussion of the harem. Varya naturally disapproves, but her disapproval, as always, comes off as the received wisdom internalized by a shallow recipient: “A modern woman would never agree to live as the fifteenth wife in a harem,” she snapped. “It’s humiliating and altogether barbaric.”

The French Paladin explains why the harem makes sense in the East (“from the very beginning, Muslims have been a nation of warriors and prophets,” neither of which have a good life expectancy). Varya protests that there must be a better way to ensure a decent living for Muslim women, only to be told “The society of the East is sluggish and little disposed to change, Mademoiselle Barbara.” Her name here has been Frenchified, but it also points to a possible British reference: is Varya another Major Barbara?

The men then laugh over stories of harem women being tossed into the sea and drowned. Varya, that feminist killjoy, somehow doesn’t think this is funny. But she is quickly mollified by Paladin's story of an enlightened padisah’s wife who singlehandly brings Western freethinking to both the harem and to Turkey in general.

Paladin's tale he tells is both true, in that he didn’t invent it, and most likely a mystification (according to the scholarly consensus). Nakşidil Sultan (c. 1767-1817) was the mother of the Sultan Mahmud II, a reformer whose liberal sensibilities are often attributed to his mother’s influence. But the version Paladin tells is a popular myth about Aimée du Buc de Rivéry, an heiress who went missing in her youth. The story has it that Aimée was kidnapped by pirates and sold to the Turkish harem, where she became the sultan’s favorite wife, Nakşidil. Chrstine Isom-Verhaaren handily dismantles this particular myth, while also analyzing its persistence and influence. By attributing a set of Turkish reforms to the influence of a French noblewoman (distantly related to Napoleon Bonaparte, no less), this myth manages to have its Orientalist cake and eat it, too: the Turks really are “savage,” and only an enlightened Westerner can bring improvements to the Ottoman Empire. As Paladin concludes his tale: “Ever since then Turkey has looked toward the West.”

Akunin stops short of debunking this particular myth, but he does insert a note of skepticism through the words of the Irish journalist Seamus McLaughlin:

“You’re a great spinner of tales, Paladin. […] No doubt you stretched the truth and embroidered it a little, as always.”

The Frenchman smiled mischievously without saying a word

By this point, the reader should have begun to notice a particular flaw in The Turkish Gambit as a work of fictional Turkish ethnography: so far, we have been in the near-exclusive company of European Christians talking about the East from an encampment in the Christian-held Balkans. But is this a bug, or a feature?