Abby Latour is a journalist based in New York City. For more information about this project, email 90srussia@gmail.com, or see @early90srussia on Instagram.

This is Part II in a three-part series. Part I ran yesterday, 11/19, and Part III will run on Thursday, 11/21.

In Yuri Mamin’s 1993 film Window to Paris (Okno v Parizh), residents of St. Petersburg discover a room with a magic mirror. Stepping through it leads one directly to the streets of Paris, where glittering stores are full of goods to buy.

Russian material culture from August 1991 through October 1993 suggests that interest in tourism and international travel was paramount at the time. Many of the objects in my collection from this period pertain to travel, including items meant to accompany Russians traveling abroad, ones for visitors to Russia, and souvenirs from travel to Russia.

During the Soviet years, travel was controlled through passport issuance, a system of internal passports, and permits to certain destinations. Under Stalin, travel had been impossible for most citizens except government officials, KGB agents, select trusted journalists, and cultural and political diplomats. Under Khrushchev’s de-Stalinization policies in the late 1950s, places that were once off-limits to Soviet citizens became less so. By the mid-1960s, many Soviets had traveled abroad, mostly to Eastern Europe, often to sightsee or to visit health spas in socialist countries like Varna in Bulgaria.

Russian language learners are likely familiar with the adage, which rhymes in Russian: “Kuritsa ne ptitsa, Bolgariia—ne zagranitsa” (Like a chicken is not a bird, Bulgaria is not a foreign country.) Reform-minded efforts of the early 1990s implicitly acknowledged this problem, so that the 1993 Russian constitution guaranteed citizens the right to travel within the country and overseas. But as travel opportunities for Russians expanded, cost placed them out of reach for most. The “magic mirror” in Window to Paris would have come in handy.

Objects I saved from 1991-93 reflect the advent of widening global travel, including to and from Russia. My research project surfaced a Russian-language travel guide to the US, “Poezdka v Ameriku: Prakticheskiї putevoditel’” (Travel to America: A practical guide), published in 1991. By the early 1990s, Russian publishers in the early 1990s had begun to respond to market demand for titles, including from readers eager to learn more about traveling abroad. Russians’ knowledge about foreign countries was typically confined to literature and films, so this informational guide would have been particularly helpful in the pre-digital age. It told readers how to obtain visas and buy airline tickets to the US (answer: at PAN AM’s Moscow office, Dobryninskaya street, near Oktyabrskaya metro station).

The book included information to help Russians understand US culture, beginning with 1492, when Columbus “discovered America,” and ending with Jan. 17, 1991, when the US and allies launched missile strikes on Iraqi targets. It offered advice on how to converse with Americans, telling readers that, if they smoked, they did not need to offer a cigarette to the person standing next to them (“that’s not done here”). The book also cautioned Russians never to ask an American how much they earn or how they make money. The guide also warns readers never to discuss illness or “everyday difficulties.”

In the 1990s, it was not just Russians who wanted to travel. As borders opened and travel requirements eased, foreigners arrived in Russia through cultural and educational exchanges. Although foreign tourists regularly traveled in the Soviet Union beginning around 1960, now they entered Soviet territories more freely, including ones that had been previously inaccessible, or were unlikely tourist destinations.

Many intrepid travelers of the 1990s returned from Russia with stories of being the first foreign visitors to previously closed cities, as well as to far-flung and “exotic” destinations like Magadan, Murmansk, the White Sea coast, Vladivostok, Lake Baikal, Tashkent, Samarkand, Yalta, and near Chornobyl.

The Soviet Union had a history of “closed cities” that were centers of sensitive scientific endeavors like nuclear weapons research. Previously unmarked in maps, some of these places suddenly became possible tourist destinations. In 1994, the Russian government published an annual handbook of statistics that named dozens of previously closed cities, mostly in the Urals and Siberia, alerting most to their existence for the first time. Not all destinations in Russia were as challenging to reach as those, however. Many were simply geared toward domestic tourists, rather than international ones.

My collection of objects includes a pocket address book from Suzdal with a calendar for the years 1992-94. Suzdal is an ancient town once developed by the government as part of a circular tourist route in the 1960s, called the “Golden Ring.” A visit to Suzdal is typically paired with one to neighboring Vladimir, now accessible by high-speed train as a day trip from Moscow. Suzdal’s skyline is best known for the Cathedral of the Nativity, with its trademark blue domes and golden doors, built in the 13th century and reconstructed in the 16th century—a landmark displayed on the address book’s cover.

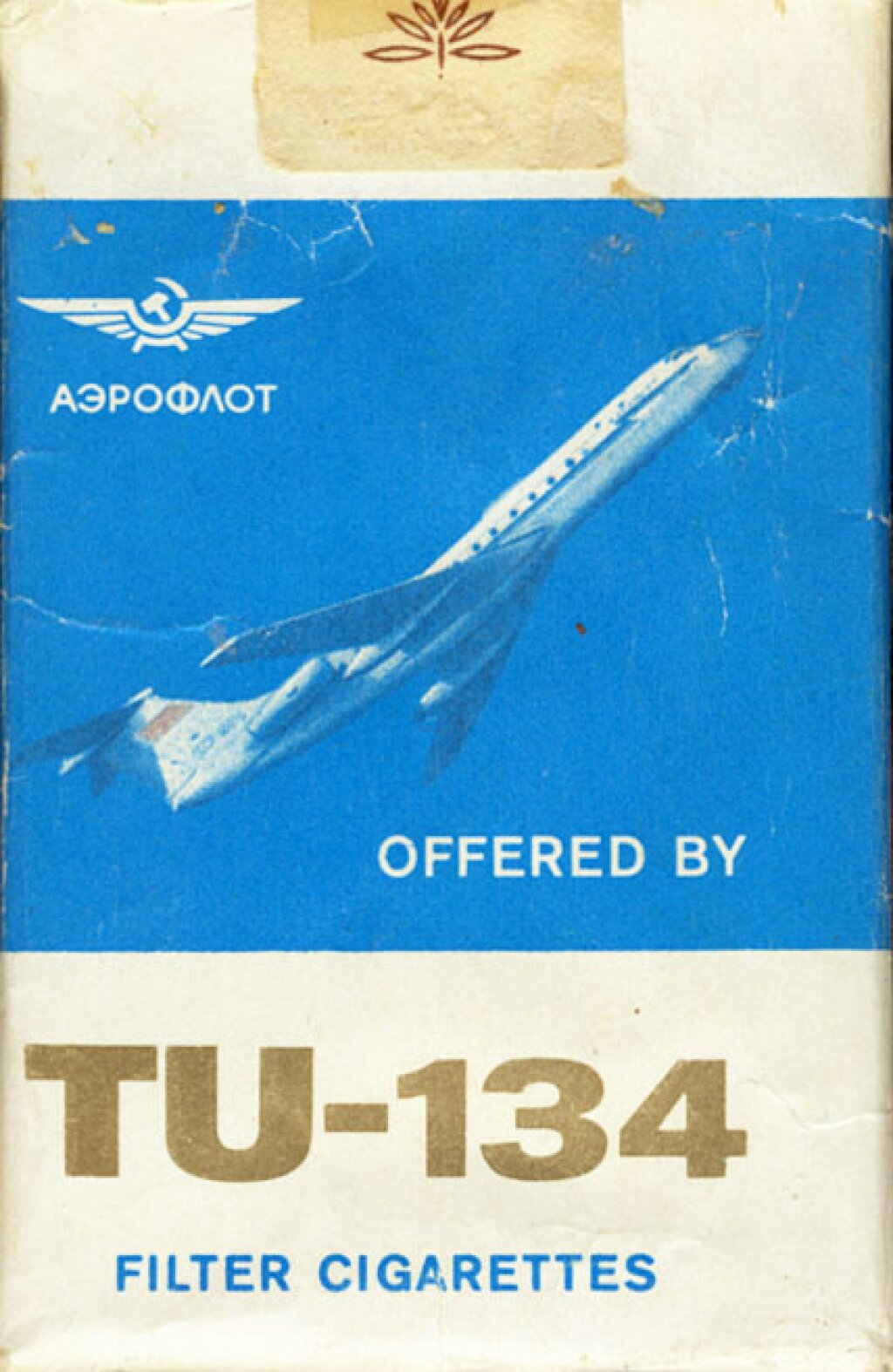

Another object I surfaced is a pack of cigarettes available to passengers onboard an Aeroflot flight between Chicago and Moscow in 1992. Many international visitors to Russia arrived via Aeroflot, the national carrier of the Soviet Union and later of Russia. In the early 1990s, its flights regularly stopped for refueling at Ireland’s Shannon, the westernmost non-NATO airport.

Historically, Aeroflot flew exclusively with Soviet aircraft, but in 1992 began using planes made by foreign companies like Airbus and Boeing. This cigarette pack would have been a nostalgic nod to the Tupolev TU-134, one of the most popular Soviet-produced aircraft that was in common use by Eastern European national carriers. Cigarettes on a flight would have also been remarkable since US regulators started banning smoking on airlines beginning in 1988, although the measure was not applied to US-international flights until 1995. Aeroflot, meanwhile, remained one of the world’s friendliest airlines for smokers and continued to allow smoking until 2001, long after most other airlines worldwide forbade it.

Sadly, many places that enjoyed a renaissance of tourism in the early 1990s are now once again off-limits. As of September 2023, as a result of US opposition to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the US State Department has classified Russia with a “Do Not Travel” designation for US citizens due to risk of wrongful detention, kidnapping, and arbitrary enforcement of local laws. Those developments are germane to the origin of one of my objects: a personalized ceramic sipping cup for the healing waters of Goryachy Klyuch, a town roughly 40 miles (60 km) from the Black Sea coast known for gorges and hiking.

Goryachy Klyuch is located in Krasnodar Krai, which is connected to Kerch by a bridge that Ukrainian forces damaged in 2022 in order to disrupt a critical Russian military supply route. My souvenir ceramic cup thus memorializes a time that increasingly appears to be anomalous in modern Russian history. In the early 1990s, many hoped that this part of the world would become like any other European country—peaceful, prosperous, and interconnected. The cup commemorates a time when beautiful and remote corners of Russia were opening to the world, a trend that has been gradually reversing since the mid-2010s and accelerated after February 2022. Today, for the foreign visitor, these magical places feel as remote as if they only existed on the pages of literary classics, in films, and in our imaginations. For me, this souvenir commemorates a bygone time and is far more precious now than when I acquired it—priceless, even.