This post is part of Chapter 3 of Russia’s Alien Nations: The Secret Identities of Post-Socialism, an ongoing feature on All the Russias. It can also be found at russiasaliennations.org. You can also find all the previous entries here.

An earlier version of part of this chapter was originally featured on plostagainstrussia.org, as Chapter Four. It was not included in the final manuscript.

Should we really be surprised that the Russian Orc, though born in late-Soviet misreadings of Tolkien, has found its natural habitat on the Internet? The Internet has been a bestiary of creatures real and mythological since its foundation: haunted by daemons and (mail)chimps, providing an alternative to snail mail and a pool for both phishing and cat fishing, while serving as a haunted house for ghosting, the Internet is home to species predatory and mild. Its most infamous resident shares some crucial cultural DNA with the Orc: I speak, of course, of the troll.

Internet trolls, like Orcs, are creatures defined by aggression. They don’t just seek out conflict; they create it. As individual independent actors, trolls spend their time online baiting their victims. If they make you angry or start an argument, they have already won. But the past decade has shown the power trolls can have when they band together (as a “troll army”), harrassing their targets with death threats, doxing, swatting, and photoshopped porn images. It took the wider world some time to recognize the effect trolls can have, in part because the stories covered in the media involved communities that, though large, are almost invisible to outsiders: gamers, science fiction fans, comics fans. Not to mention the inevitable downplaying of the threat when its most visible targets were women.

Or at least that was the case in the West. As far back as 2003, Anna Polyanskaya, Andrei Krivov, and Ivan Lomko alleged that a radical shift in the political content on the Russian Internet after 2000 may have been there result of state security interventions. In 2013, a report for the St. Petersburg Times wrote that the St. Petersburg-based Internet Research Agency was employing people to write pro-regime comments on blogs and other websites. By the time the Agency was profiled by Adrian Chen in the New York Times just two years later, the Agency and organizations were known widely as “troll farms.”

At this point, I wish I could say that the rest is history, but, sadly, it’s current events. The run-up to the 2016 American election saw a series of reports on the activities of paid Russian Trolls fanning the flames of white nationalist fear in social media under false names, spreading conspiracy theories, demonizing Democrats and migrants, and making sure that the words “Benghazi” and “Hillary’s email” would never disappear from the news feed.

The success of Russian trolling within the American informational ecosystem is unparalleled, but not necessarily because of the effects of any particular troll campaign. Russian trolling in America is a boss-level victory, upping the ante from trolling to meta-trolling by spawning intense paranoia about Russian trolling. When people on the American Left, so traumatized by this MAGA nightmare, starts looking for Russian trolls under every bridge they cross, they have fallen into a Foucauldian trap. Like the denizens of the panopticon who get into the habit of surveilling themselves because they never know if they are actually under surveillance, Americans who are paranoid about Russian trolls are trolling themselves.

Whether by design or by accident, Russian trolls have fulfilled a fantasy whose roots lie not in Tolkien, but in pre-Newtonian physics. They have turned trolling into a perpetual motion machine, one that no longer actually needs them in order to function. Like the deistic conception of a God as First Cause, creating the universe and then stepping back, Russian trolls, should they choose, have the luxury of simply sitting back and enjoying their handiwork as spectators. It works because the nature of this machine is virtual and informational, a triumph of memes over matter. While the jury is still out as to whether the fictional troll should be considered a mammal or a reptile, the Russian troll is oviparous, a cuckoo bird laying its eggs in the minds of anxious Westerners who will raise its offspring as their own.

What does this have to do with Russian Orcs? If the American victims of Russian trolls are self-trolling, the Russian Orcs are, to use an Internet term of art, self-owning. In each case, we have a complicated problem of self and other.

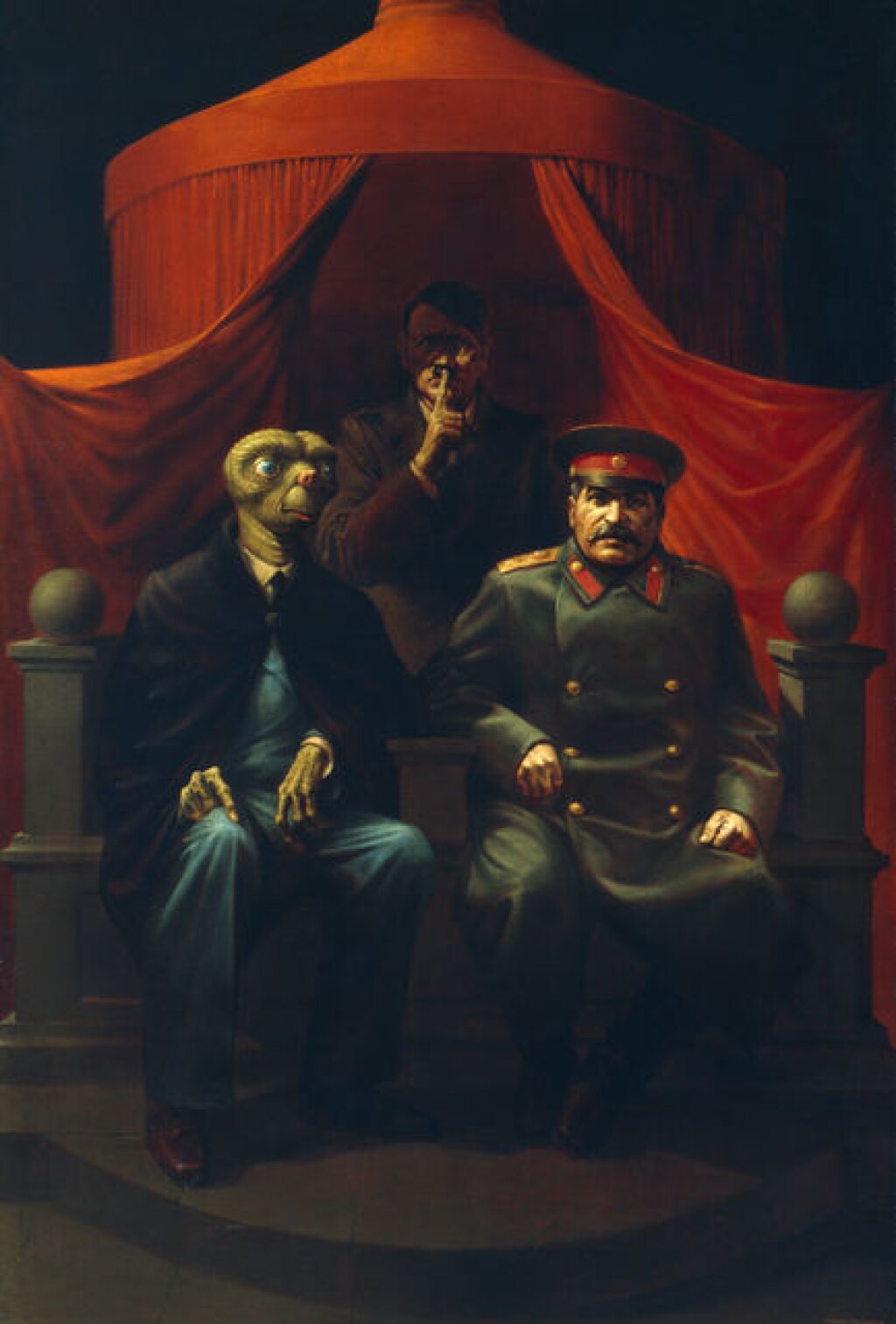

On the Internet, the Orc can be seen as a particular variety of troll. Both Orcs and trolls have broad, abstract targets in their sites: liberals, snowflakes, SJWs, feminists, and so on. The troll wages war against the abstract enemy by focusing on specific targets and engaging in coordinated campaigns. The Orc is comfortable remaining at a high level of abstraction. Though the metaphor doesn’t fit their respective mythologies, trolls are ground troops, engaging their enemy in hand-to-hand combat; Orcs are masters of ideological drone warfare.

But the Orc will never be as successful as the troll. This is not just because the definition of the Orc is so easily hijacked by the enemy, but because the very notion of the Russian Orc is based on a faulty premise about self and other. The Russian Orc is a reappropriation of an anti-Russian meme for pro-Russian purposes, yet, before the war in Ukraine, the equation of Russian and Orc existed almost entirely within Russian-language cultures, based on a reading of Tolkien that few in the West were inclined to make. The Russian Orc is a double projection: projecting onto Westerners the projection of Orcs onto Russians. Proponents of the Russian Orc are defiant, but defiant in the face of nothing, since no one was calling Russian Orcs except for Russians themselves.

This does not render the Russian Orc idea ineffective, just intramural. The final post in this chapter will explain why.

Next: Nationalism as Fandom