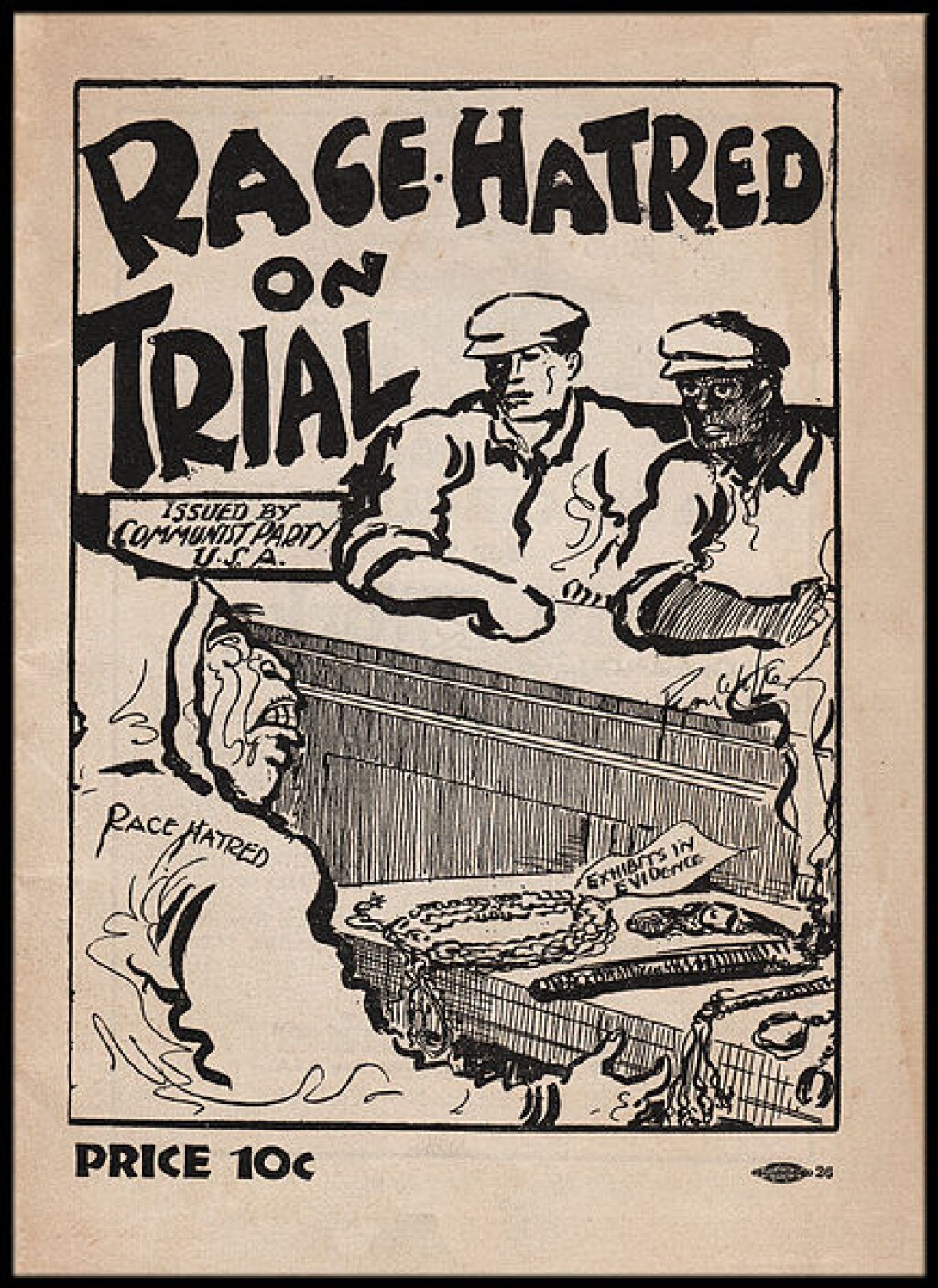

On September 21st, Sean Guillory, host of the SRB Podcast and Digital Scholarship Curator in the Center for Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies at the University of Pittsburgh, joined the Jordan Center and Yale University’s Program in Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies for a talk on the Yokinen trial, “A Trial Against Racial Hatred: White Chauvinism and International Communism.”

Guillory became interested in this topic because of its relevance to the discussions of racism and anti-racism taking place in the United States today. He explains that in the 1920s and 30s the Communist Party of America was dealing with the issue of racism in American society and institutions and trying to answer the question of how a communist was supposed to be anti-racist, what it meant to be anti-racist, and what the parameters for acceptable and unacceptable behavior were.

The Party had been, as Earl Bowder put it, “on the alert searching for just such issues as the Scottsboro case to organize the anti-racist struggle around.” The incident that led to Yokinen’s trial took place at a Finnish dance hall in Harlem where a group of white members intimidated a group of Black dance-goers. Yokinen, a janitor at the dance hall, failed to intervene. In the New York Control Commission investigation that followed, all white participants recognized their guilt, save Yokinen, who took it further.

“If Negroes came into the club and billiard room, soon they’d be coming into the baths, and I don’t want to bathe with Negroes.”

He examined the Yokinen trial because it was the first show trial in the history of the American Communist Party. Previously, he explained, the Party had dealt with ethical violations, disciplinary violations, and ideological deviations behind closed doors through the Control Commission. Why then, he asked, did the Party make such a public spectacle of Yokinen?

In the years leading up to the trial, the Communist Party had made several attempts to address racism. The Black Belt thesis, written by Harry Haywood in 1928, advocated for Black self-determination in the Black Belt, sections of the South in which African Americans made up the majority of population, and was one of the first instances that the American Communist Party made a clear statement about what they called “white chauvinism.”

A Communist-Party front, the League for the Struggle for Negro Rights followed in 1929, but Haywood and other Black leaders referred to the organization as a Jim Crow organization because all Black work and issues were relegated there.

In January 1931, Cyril Briggs, Harry Haywood, Herbert Newton published “A Statement of Several Negro Comrades Concerning Negro Work.”

“The Party’s activities among the Negroes has not shown any marked progress [...] In fact, during the investigation of the incident of the FInnish Club, a comrade by the name of Yokinen expressed the rankest hating sentiments, inferring that Negroes should not be allowed in the pool room and bathrooms”

A nine-hour meeting among Clarence Hathaway, Earl Browder, Cyril Briggs, B.D. Amis, Harry Haywood, and Maude White followed the statement. Emotions ran so high, Guillory explains that White left the meeting in tears, and Briggs yelled so loudly that his stutter disappeared.

The trial was announced in The Daily Worker on March 1st, 1931. It was unclear why Yokinen, who was a Finn, was chosen as an example, but Guillory argued that he fit a certain profile. 65% of Communist Party members were foreign-born, and ethnic identity was strong in the Party. A lot of incidents of racism occurred in spaces among white ethnic groups—including Ukrainians, Lithuanians, and Jews. Finns were the largest group after Jews.

Guillory described the carefully constructed trial: of 14 jury members, half were white, half Black. The prosecutor, Clarence Hathaway was white; the defense attorney, Richard Moore, Black.

Hathaway argued,

“This attitude is a very dangerous one… Comrade Yokinen was giving another indication that his was only a formal acceptance of equal rights for Negroes without accepting it in practice. He was ready to adopt a resolution for equal rights, but he did not want to grant equal rights in the Finnish Workers Club.”

Moore countered,

“Examine yourselves! Have we carried on within the various workers’ organizations and whitin the CP itself a broad campaign of education to stress the importance of this question, to clarify the workers and root out chauvniist prejudice against the Negro workers? We have not sufficiently carried out this task and this is one of the reasons why this rank and file worker has committed this crime… we ourselves share the crime of Comrade Yokinen.”

At the conclusion of the trial, the Party expelled Yokinen but allowed him the opportunity to redeem himself by putting himself at the head of the struggle against racism.

The day after the trial, an arrest warrant was issued for Yokinen. He was arrested and then bonded out of jail by the Communist Party, who attempted to defend him in court. Although his case made it to the Supreme Court, they were ultimately unsuccessful, and he was eventually deported to the USSR where he survived the war and worked in a factory.

On the same day that the Supreme Court ruled against Yokinen, it ruled in favor of the Scottsboro Boys, giving the Communist Party and America a victory in the struggle against racism. Within the Party, the Yokinen trial spawned a slate of smaller, “mass produced” show trials that Earl Bowder described as “Model T white chauvinist trials.”

For the Communist Party, Guillory argued, anti-racism was a prerequisite for class struggle. It was about building a better world through socialism. As he concluded, he left his audience with a question: what is the goal of anti-racism today? What are we trying to achieve? What is the better society we imagine?

During the Q&A, Guillory explained how the trial and white chauvinism affected genera; American society. He said there was much celebration of the trial amongst Black press. More generally within American society, it was put into the frame of poisoning Blacks with “anti-racism,” a bolshevik plot. In the 1920s, there was a crystallization of white supremacy and anti-communis, and being an anti-communist and being a white supremacist are very connected.

He also explained that there were not many references to gender in connection with the effort to exclude Blacks from the Finnish Hall and trial. He said the only time they make a gendered reference, they point out the “lie” of black men preying on white women.

Finally, he elaborated on the relationship between the American Communist Party and the Civil Rights movement. He explained that there was a revival of the campaign against white chauvinism in the 40s. By the 50s the party was faced with legal action and deportations of Party members. The civil rights movement as it emerged tried to distance itself from the Communist Party because it was equated with a foreign, hostile power.