This is Part III of a three-part series. Part I may be found here and Part II here. A version of this piece originally appeared on Gorky Media.

Ilya Vinitsky is Professor in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures at Princeton University. His fields of expertise are Russian Romanticism and Realism, the history of emotions, and nineteenth- century intellectual and spiritual history.

Translated by Emily Wang, Assistant Professor in the Department of German and Russian Languages and Literatures at the University of Notre Dame.

5.

The first issue of cultural and political weekly Literary Gazette [Literaturnaia gazeta] for 1934 included an item sympathetic to the cause of literary cafés, in particular highlighting the significance of Kol’tsov to this endeavor. The piece described the “hundreds of qualified” journalists, workers in publishing, and writers located in Moscow, who thus far had lacked a creative center of their own, catering to the “cultural and daily needs of journalists and writers." At long last, a model club of this type — the literary café — had opened on the initiative the House of the Press. Krokodil staffers and the three-cartoonist collective known as the Kurkryniksy were all invited for a visit. Two rooms in the literary café were “designed in an interesting way,” according to the article. The first was dedicated to “cartoon sketches of writers, poets, journalists, artists,” including “witty caricatures” depicting the likes of Zharov, Utkin, Aseev, Kirsanov, and the satirists Ilf and Petrov, shown “crouched hungrily over their Golden Calf.” In turn, Mikhail Kol’tsov was shown “on a pedestal in the guise of a Statue of Freedom — a ‘Man with Little Flame [Ogoniok],’” with a snapshot of the image to follow. In the next room, viewers confronted “a mural depicting a satirical fantasy history of the newspaper from prehistoric times up until the present day.” “All this,” remarked the article's author, “is new and original.” This was not technically true — "all this" was actually an imitation of Western examples, like the legendary Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, where Lenin once played chess with Tzara, as well as pre-Revolutionary Russian literary cafés — though the establishment profiled in the 1934 issue of the Literary Gazette was equipped with optimistic Soviet innovations. Among the café’s famous visitors, Mikhail Kol’tsov was named first of all, followed by B. Efimov, S. Kirsanov, L. Nikulin, F. Raskol’nikov, E. Zozulia, A. Arkhangel’skii, B. Malkin, the Krokodil collective, and others. The article's author expressed a desire that this literary café might give rise to, as its builders promised, a “frontline of journalists and writers” and that “from the stage would resound not only the orchestra, but also the language of the writer, the poet, and the journalist."

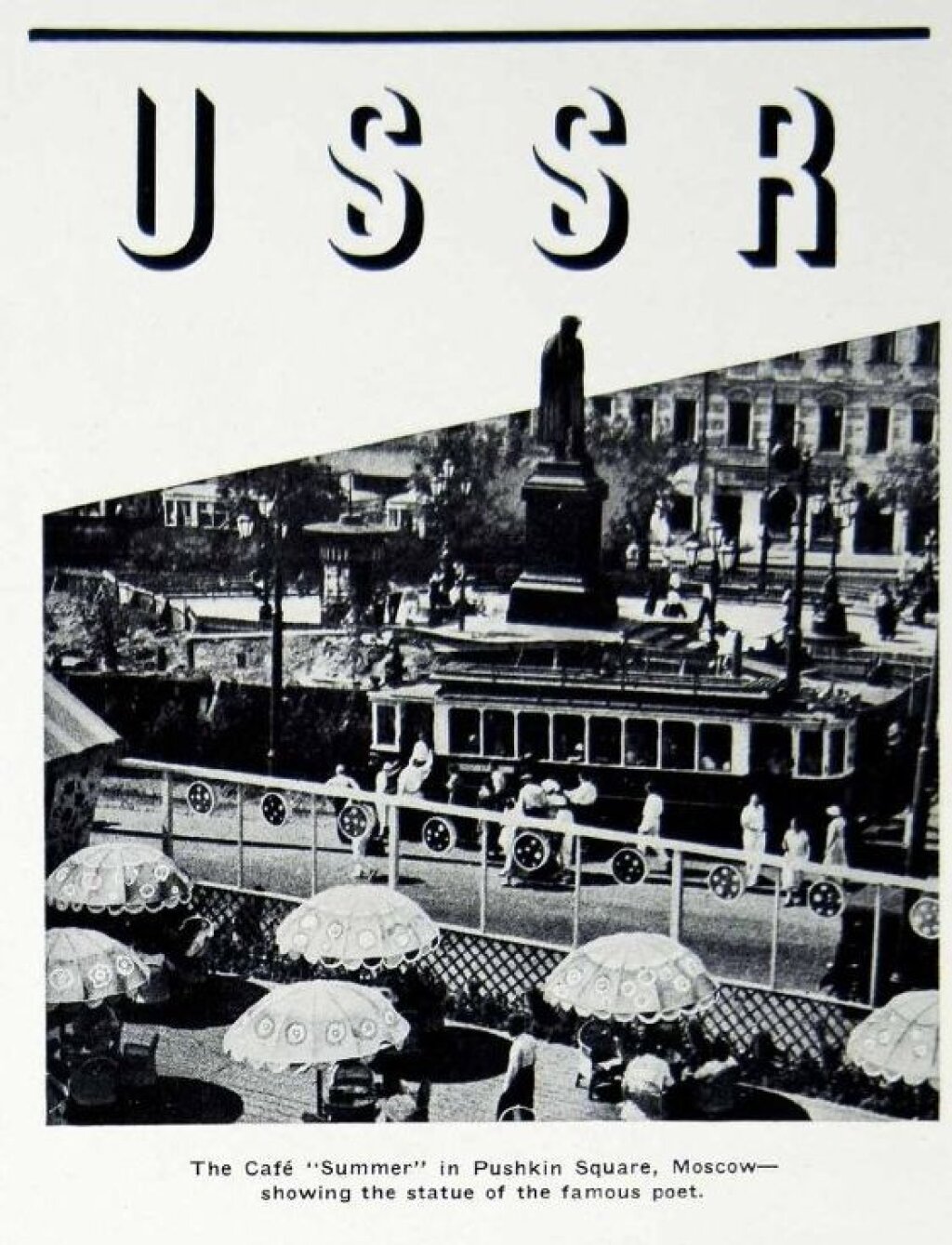

The author juxtaposed this model literary café with the newly opened “café in Herzen House” on the other side of Pushkin Square, which was notable, in his opinion, for its extremely vulgar taste: “I wonder who was imagining writerly taste when ‘designing’ this café? A vulgar bourgeois ‘mural’ may gladden the heart… of a pub owner or the kindly old proprietress of a tea-room for cab drivers.” It was no accident that “in the very first days of its opening” this design “provoked numerous protests from literary people.” The author continued, “it was necessary to redecorate the café without delay,” and “to invite artists, and not house-painters” — in a word, “to take a page from the book of the House of the Press." As with the Pushkin Café, the theme of restaurant vulgarity is key to the takedown of this establishment. In this case, however, what is condemned is not the establishment's inappropriate name, but rather its archaic, tasteless design. Moreover, those called upon to do battle with it were to be professional artists, not state power.

The origin of the Moscow café renaissance that took place the year of the Writers’ Congress stemmed not only from the city government’s desire to create a suitable place of leisure for the creative intelligentsia and foreign guests of the capital, but also from the spirit of Soviet “epicurean bohemianism." This was a utopian vision of a new, happy Moscow — one that celebrated its own existence joyfully and in an entirely earthly way. In this sense, the earlier statement from the director of Café Pushkin (unfortunately, I still haven’t been able to identify him) about the future restaurant “paradise” of the USSR is quite characteristic.

It would not be an exaggeration to say that this gastronomic celebration of the life of the capital’s creative intelligentsia took place under the sign of Pushkin, as though his cheerful shade had come to visit this world again. One of the key cultural events that year was the discovery, in the Pushkin House Archive of the Soviet Academy of Sciences, of the ribald poem “The Shade of Fonvizin.” Mingled among the papers of Prince Oleg Romanov, which appeared to represent Pushkin's frivolous side. In the atmosphere of 1930s satirical journalism, this hedonistic poem, filled with literary polemics, took on a particular relevance.

In connection with this point, let us return to the godfather of the café on Pushkin Square, Mikhail Kol'tsov. One of the leaders of Soviet journalism and member of the Pushkin Committee, he was depicted, we’ll recall, on the wall of the journalists’ café in the guise of a Statue of Freedom. Evidently, he was the specific target of the crusade against vulgarity. As far as we know, no answer from Kol’tsov to Kaganovich’s inquiry survived, but it’s worth noting that the October and November issues of Krokodil (which employed Boris Yefimov, the journalist's brother and a famous cartoonist in his own right) featured some texts that poked careful fun at the purists’ ban on a name considered inappropriate for a café. One of these texts was styled as a parody of a Soviet encyclopedia entry from the “KSE" or "Krokodilian Soviet Encyclopedia," a "dictionary of generally useful expressions, technical formulas, all-purpose names and philosophical systems, as well as polite expressions and transportation terminology. Compiled from academic sources, plaintiff’s testimony, and the authors’ personal experience.” The "dictionary"'s entry for “Pushkin, Alexander Sergeevich” included only two words: “former café” (Nos. 29-30). In another feuilleton describing the imaginary election of delegates to the Moscow Soviet from the ranks of classic Russian writers, his fellow authors reject Pushkin’s candidacy because “he had been recently de-kulakized: they took away his last café!”

These jokes, it seems to me, express a generalized annoyance on the part of the Kol’tsov “group” of writers and artists toward hypocrites and obscurantists within the Party. Unfortunately, the specific cartoon Baird writes about cannot be located at this time, but it mostly likely existed. However, in all likelihood, this cartoon should be interpreted not as a condemnation of the vulgar choice of the café’s name, but rather as an innocent joke made within the framework of a lively public debate. To a significant degree, one can regard the campaign against “Café Pushkin” as one of the prototypes of future attacks on ironic and humorous desacralization of the poet’s image.

From the end of 1934, it became clear that it was already impossible to joke about the café’s name, for the “battle with vulgarity” (including the “cowardly-giggling” variety) had taken on a new, even more menacing tone. On December 1, 1934, Politburo member Sergei Kirov was killed. His murderer, in accordance with Bedny’s mythologizing logic, could be seen as a new incarnation of “the fascist murderer Dantes” — an agent of the vulgarity engulfing the globe, now branded with suitable political epithets: “socio-fascist vulgarians,” “bloody vulgarian,” “vulgar and liberal giggling.” Doomed also was the entire Moscow restaurant group, which had made the political mistake of naming the erstwhile Pushkin Café after the famous poet. Its directors, the famous Chekist Yan Ol’sky and the young director Seraphim Stolpovsky, were shot in 1936 and 1937, respectively, while Kol'tsov, who had prompted the naming episode, was himself arrested in 1938. Stolpovsky was charged with organizing the "terrorist workers’ group Mosnarpit,” made up of cooks and other serving personnel. Its goal, in the words of Nikolai Yezhov, who helmed the NKVD from 1936 to 1938, was to poison members of the government at “the very first opportune moment, upon being asked to organize some kind of banquet.”

Gorky did not live to see all this, having died in the Party elite dacha at Gorki (Горки) on June 18, 1936. But immediately after his death, rumors began to spread that he had been poisoned by chocolate candies sent to him from the Kremlin. Whether this is true or not, nobody knows. One thing is certain, however: even had he been poisoned, the efforts of this great warrior against vulgarity would have ensured that the chocolate was at least free of Pushkin's name. To be fair, however, the box of assorted desserts produced by the Bolshevik Baked Goods Factory in 1936 still included a biscuit called “Pushkin."

The incident with “Café Pushkin” is interesting in a purely literary and "mysterious" sense, relating to the depiction of another “named” restaurant where jazz was played and vulgarians, libertines, and sycophants reigned. I mean, of course, Bulgakov’s “Griboedov,” a writers’ restaurant modeled, as most believe, on the very same “Herzen House” where, in the words of the author of the piece in Literary Gazette, a “vulgar” restaurant for writers was opened in 1934. Doesn’t Bulgakov’s satire carry overtones of the scandal surrounding the cursed café on the corner of Gorky Street and Pushkin Square? Speak of the devil…

For Bulgakov, just as for his antipode Bedny, the themes of vulgarity, bootlicking, gluttony, and servility were not only united together, but connected to the main “threat” against Pushkin as incarnation of aesthetic and moral truth, his monument and the image of Dantes. In this sense the famous episode with the mediocre poet Riukhin, who spoke of Pushkin and his fame with bitter jealousy, brings to mind not only Mayakovsky’s “Anniversary,” but also Bedny’s poem “Genius and Vulgarity,” which contains an entire set of “vulgar” qualities and jealous rebukes of the great poet on the part of young contemporary writers. Bulgakov, in other words, operates in the very same Pushkin-centric system of coordinates, but from a different perspective and with a completely different, although no less ideological, conception of vulgarity. Between 1933 and 1934, he would write a four-act play about Pushkin’s final days in which the poet himself never appears — “otherwise it would be vulgar.” In turn, Bulgakov’s treatment of Dantes rejects not only the political demonization of Pushkin’s murderer presented by Bedny, but the naïve Pushkinist interpretation of the murderer as a “grotesque little ballroom officer,” in the words of writer Vikentii Veresaev.

6.

What happened to the Pushkin café after it lost its honorable name? In a collection of photos from 1935-6, there is a photograph of the popular Summer Café on the corner of Pushkin Square at the former location of the Church of Dmitry Solunksy (which had been removed), but this café is open. Yuri Fedosyuk tells us that “Café Pushkin” was renamed “Sport.” Then this café “turned into an exclusive restaurant in the House of the Actor, where nobody but actors and performers could come in from off the street." The unexpected and, in its own way, symbolic resurrection of “Café Pushkin” would not take place until the middle of the 1960s. In his famous song “Nathalie," Gilbert Bécaud sings:

Elle parlait en phrases sobres

De la révolution d'octobre

Je pensais déjà

Qu'après le tombeau de Lénine

On irait au café Pouchkin

Boire un chocolat.

[She spoke in sober terms

Of the October Revolution.

I already thought

That after the Tomb of Lenin

We would go to Café Pushkin

And drink hot chocolate.]

There is a certain irony in this song, unremarked upon by its many admirers in Russia, as far as I know. The elegant French singer invites a Russian tour guide named Natalya, who has caught his fancy, to partake of chocolate — a well-known erotic symbol and aphrodisiac — in a café named after Pushkin. Would the keen Demyan have seen this turn as a vulgar travesty of the memory of the poet and his wife?

In turn, Bécaud’s song served as inspiration for the Franco-Russian artist and restaurateur Andrei Dellos, who opened an elite restaurant featuring “nobleman’s cuisine” called Café Pushkin in Moscow in 1999 — that is, on the two-hundredth anniversary of the poet’s birth. In Dellos’ words, French admirers of the song had been looking for a café with such a name in Moscow and, it seems, never managed to find one. In 2012 a café with this name opened in New York on 57th Street, but soon closed “after a series of mixed reviews.” “Bolshevik taste,” which had chased Pushkin’s name from the tavern, was replaced by an aesthetic of postmodern irony closely linked with a commercial instinct for the new Russian elite’s nostalgia for an elegant cuisine that Pushkin had immortalized in his long novel in verse, Eugene Onegin (here quoted in James E. Falen's translation).

He’s off to Talon’s, late, and racing,

Quite sure he’ll find Kaverin pacting;

He enters – cork and bottle spout!

The comet wine comes gushing out,

A bloody roastbeef’s on the table,

And truffles, youth’s delight so keen,

The very flower of French cuisine,

And Strasbourg pie, that deathless fable;

While next to Limburg’s lively mould

Sits ananas in splendid gold.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

If you enjoyed this series, please consider subscribing or submitting to The Pushkin Review, a peer-reviewed annual journal published by the International Pushkin Society. Issue 21 will be available at ASEEES 2019. Those interested in receiving Pushkin Review, including back issues, may write Slavic Publishers (slavica@indiana.edu). Annual dues for the International Pushkin Society are $30, and come with a subscription to the journal. Libraries may subscribe by contacting Slavica Publishers (slavica@indiana.edu). Some back issues are also available online through Project Muse (https://muse.jhu.edu/journal/532) and at http://www.pushkiniana.org, maintained by Web Editor Ivan Eubanks (ieubanks@ucci.eu.ky).

For article or translation submissions, write to incoming Editors Joe Peschio (peschio@uwm.edu) and Igor Pilshchikov (pilshchikov@ucla.edu). For book reviews, write to Book Review Editor Katya Hokanson (hokanson@uoregon.edu).