Andrei Kureichyk is a Belarusian playwright, director, and publicist in exile. He is a resident of the Artists at Risk Program, a Yale World Fellow, Henry Hart Rice Associate Research Scholar and Lecturer, Fortunoff Fellow and a member of International PEN.

Speaking at his 2022 Nobel lecture, Peace Prize laureate Ales Bialiatski described himself as “a human rights activist and therefore a supporter of nonviolent resistance.” Bialiatski received the honor alongside Alexander Cherkasov, chairman of Russia's Memorial Society, and Oleksandra Matviichuk, head of Ukraine's Center for Civil Liberties. Despite the war raging among these countries, the Nobel committee’s decision to place Bialiatski, Matviichuk, and Cherkasov on the same stage underscored the continued importance of joint efforts to protect humanistic values and support basic rights and freedoms.

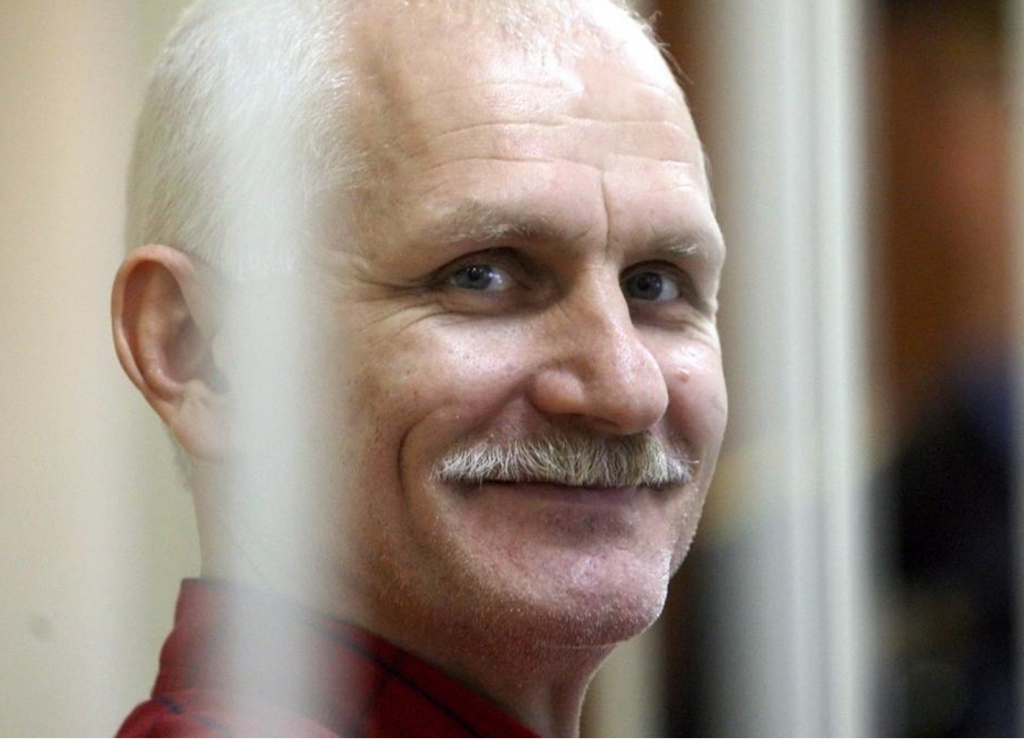

Bialiatski’s was one of the strangest Nobel lectures in history. Not only did the laureate not write it himself, he did not deliver it—at the time of the ceremony, he was in solitary confinement in Cell Block No. 1 in Minsk, Belarus. As founder of the Belarusian human rights center Viasna [Spring], Bialiatski was detained on 14 July 2021 and was still awaiting trial on politically motivated charges. His trial began behind closed doors on 5 January 2023, just a month after he received the Nobel Peace Prize. Bialiatski's wife, Natalia Pinchuk, served as her husband's voice at the ceremony. Thanks to her, millions of Belarusians finally heard what they had been waiting for: the Belarusian language spoken for the first time from the famous Nobel rostrum.

“On December 10, I want to repeat for everyone: 'Do not be afraid!' These were the words that Pope John Paul II said in the 1980s when he came to communist Poland. He didn't say anything else then, but it was enough. I believe because I know that spring always comes after winter,” Bialiatski stated at the time.

In Belarusian (and Russian), pravozashchitnik, the word for “human rights activist” simply combines the words “rights” and “defender,” resulting in a term that literally translates to “defender of rights.” The distinction with the English equivalent is subtle, but reflects an essential difference between former Soviet-bloc states and the Anglophone West. If, in the USA and Europe, human rights activism is considered an essential service to society, in Belarus it is always a defense, that is, a challenge to the authoritarian state and a direct clash with its repressive machine.

Ales Bialiatski stood up for human rights and freedoms in 1996 when he created the Viasna 96 human rights organization (later simply Viasna) in Belarus. It was in this year that it finally became clear that President Alexander Lukashenka, elected in the country's first democratic presidential elections, had chosen to establish a dictatorship. Lukashenka came to power in 1994 on a wave of resentment among large swaths of the population, which had suffered in the run-up and aftermath of Soviet collapse.

As a young activist, Bialiatski had joined the Belarusian People's Front, which helped harness energies long dormant within an artificial communist empire—energies that eventually led to its disintegration. In his Nobel speech, Bialiatski noted that, as a member of the activist underground since 1982, he finds that “it is a dramatic mistake to separate human rights from the values of identity and independence.”

Writing from a penal colony in Bobruisk in 2013, he asked,

What serious and practical people 25 years ago took into account a dozen informal communities scattered throughout Belarus? What were those [semi-underground youth clubs with names like] Tuteyshiya, Talaka, Pokhodnia, Uzgorye, and Svitanak? What power could they have when, for each activist, there were several more individuals in plain clothes, and whole swarms of Komsomol members? Who was counted among the handful of lay enthusiasts and dreamers? Who, besides us, believed that we, or, at least, someone with our help, would be able to push the Soviet machine out of its rut?

History has provided answers to all of these questions. The USSR collapsed in 1991, less because of external pressure, war, or sanctions than by the power of “lay enthusiasts and dreamers” like Bialiatski himself. 2020 was a similarly fateful year for Belarus, and for similar reasons. New generations of idealistic Belarusians had emerged who were tired of living under the dictatorship of a decrepit and increasingly incompetent tyrant. For Bialiatski, the 9 August presidential elections in that year were rife with “mass falsifications” that made people “take to the streets” in a struggle between Good and Evil. “Evil,” as always, was “well-armed,” while “from the side of Good there were only peaceful mass protests, unheard-of for the country, which gathered hundreds of thousands of people.”

Ales Bialiatski may be the first Nobel Prize winner in history to be accused of “smuggling.” The accusation stems from the monetary aid the banned Viasna center offered to political prisoners to help pay for lawyers and illegal fines. To this end, Viasna received grants from international donors and foundations, but how could these funds be delivered to Belarus? The fact that this money eventually ended up in Belarus and went to help political prisoners was defined as an act of smuggling.

During my tenure at the Coordination Council of Belarus, I was fortunate to become acquainted with, and work alongside, two Belarusian Nobel laureates: Ales Bialiatski and Svetlana Aleksievich (Nobel Prize for Literature in 2015). At 60, Bialiatski remains the same dreamer, romantic, and optimist he was at the beginning of the Belarusian liberation movement. He still has faith in peaceful protest and believes that goodness will ultimately sprout through the asphalt of repression. Despite the illegal persecution he has endured, Bialiatski is still looking for a way out of the cold civil war in Belarus.

How best to combat dictators like Hitler, Stalin, Putin or Lukashenka remains an open question. One perspective is that dictators are terrorists who take whole countries hostage. What are the rules of negotiation in this case? Is it more important to save individual people at the cost of compromise with the regime, or to maintain the principles of law and justice? These questions lie beyond pure logical analysis, requiring input from the philosophical, religious, and moral paradigms of the observer or participant. Bialiatski’s own answer is contained in his last word in court, spoken before Lukashenka's judge sentenced the only Belarusian Nobel Peace Laureate to years in prison on trumped-up charges. Sitting in a cage in handcuffs, Bialiatski said:

We need to start a broad public dialogue aimed at national reconciliation, no matter how difficult it may seem to some people. Such a dialogue must include representatives of the authorities as well as representatives of the general public, political parties and movements, those who are now in prison and those who are fleeing repression and have been forced to go abroad. We must think of Belarus as a common homeland for all Belarusian citizens, where, despite different political views and geopolitical preferences, there is room for everyone. Enough is enough, we have to stop this civil war! I hope my voice will be heard.