This post is part of an occasional series on new and recent scholarship in the field.

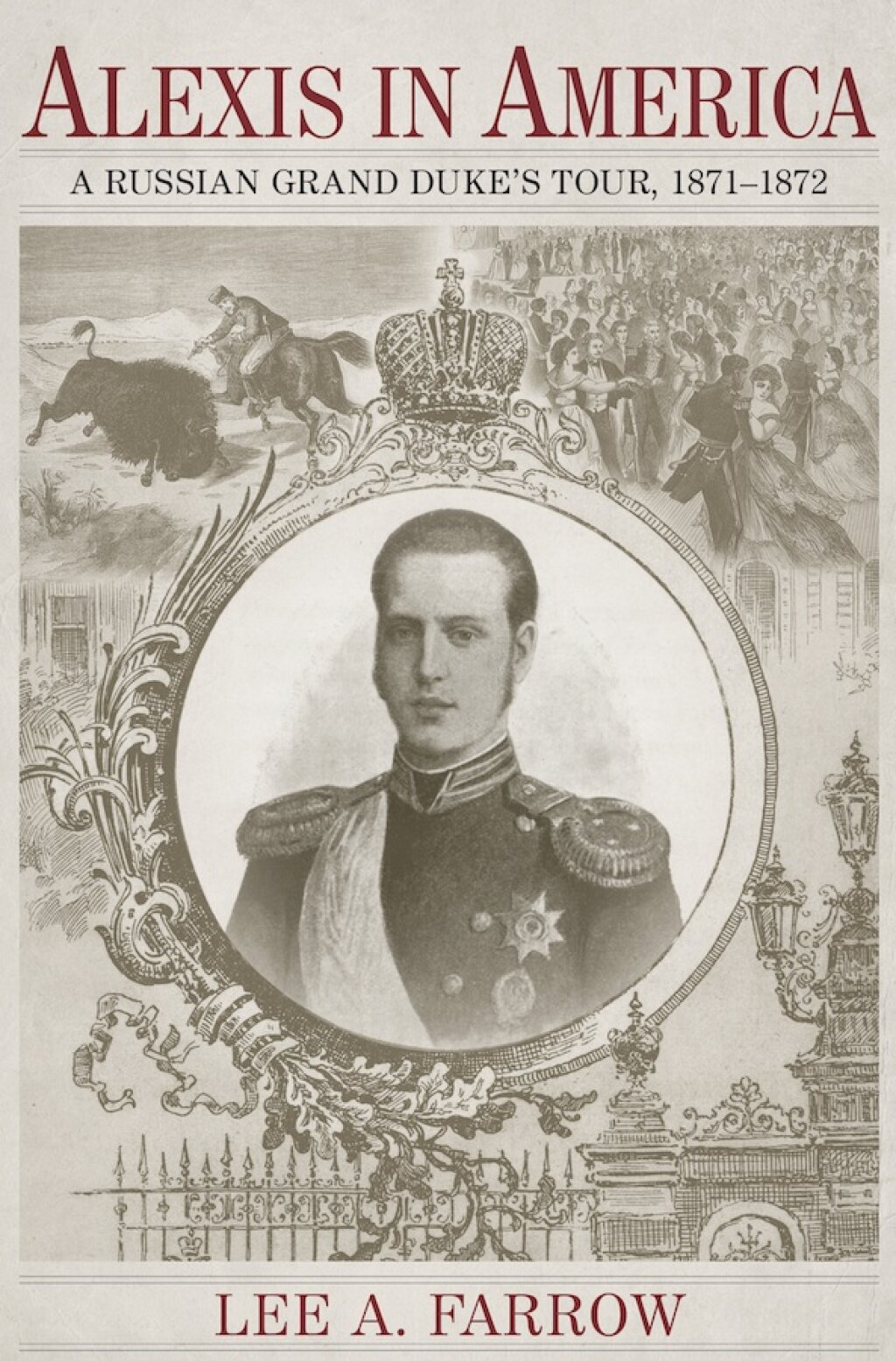

Lee A. Farrow is Professor of History and Director for the Center for Excellence in Learning and Teaching at Auburn University at Montgomery in Montgomery, Alabama. Her book, Alexis in America: A Russian Grand Duke’s Tour, 1871-2, was published in December 2014 and examines Alexis’s visit to the United States.

One hundred and forty four years ago Tsar Alexander II decided to send his fourth son, Alexis, on a grand tour that included three and a half months in the United States. In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, Russia and the United States had a very different relationship from the one that we know today. Despite their dissimilar political systems and historical development, the two nations were on friendly terms and shared certain commonalities that served to reinforce that sense of friendship. Following the abolition of serfdom and slavery, both countries were experiencing social transformations and were in the process of redefining themselves and their relationships with other nations. As the United States recovered from a brutal civil war and dealt with post-war disputes at home and abroad, Russia faced the challenges of domestic reform, a growing revolutionary movement, rebellious Polish subjects and the external threat of a newly unified German state.

There were several reasons that Alexander chose to send his son on a long journey in 1871. Alexis, only twenty-one years old at the time, was in love and deeply involved with an older woman named Alexandra Zhukovskaia, the daughter of a famous poet, but a commoner and an unsuitable choice for a royal duke. The Tsar hoped that an extended period away from home would squelch his son’s romance with this undesirable woman. But Alexander intended the trip to have a larger significance, as well; it was, to some degree, a good-will tour designed to strengthen and secure good relations between the United States and Russia. During the Civil War, Russia had supported the North; now that the country was reunited, Alexander understood the need for a newly-defined relationship. It was also the first visit to America by a member of the Russian royal family, an occasion rife with possibilities and peril. Not surprisingly, the success of Alexis’s trip was viewed by many as a barometer of Russian-American relations.

This relationship seemed constantly in danger. First, there were the persistent claims of Captain Benjamin Perkins, a merchant marine who declared that Russian agents had initiated and then defaulted on contracts with him for powder and guns during the Crimean War. The case dragged on for years and Perkins had died, but in 1867, his descendants tried to extract their losses from the U.S. payment for Alaska. Though this effort also failed, proponents of the Perkins Claim continued to agitate for its reconsideration in political and diplomatic circles. This tension was only made worse by the bad behavior of the Russian ambassador, Constantine Catacazy, whom American officials described as odious and dishonest. His insulting tirades toward Secretary of State Hamilton Fish and President Grant, and his refusal to respect the rules of diplomatic protocol and confidentiality, resulted in a request for his removal only months before the Grand Duke’s expected arrival. Many, however, said it was the “Washington wives” who had done him in because his wife, a divorcee, was too beautiful and, therefore, threatening. So serious was the matter that Alexis’s visit was almost cancelled. Once the Grand Duke had arrived, there were still complications. In many cities, officials questioned the wisdom of spending precious treasury dollars on Alexis’s reception, while in other places, German and Polish Americans opposed Alexis’s visit on political grounds. In New York, there was even a rumored assassination plot by Polish nationals, a threat taken so seriously that government officials hired Pinkerton’s Detective Agency to investigate and serve as body guards for the remainder of the trip.

Despite these challenges, the visit of Tsar Alexander II’s son to America was hailed a great success by everyone involved. Alexis was hosted and toasted in every city he visited, the honored guest at dinners, balls and special theatre performances. He participated in a buffalo hunt out west with Buffalo Bill Cody and General George Custer and witnessed the first daytime Mardi Gras parade in New Orleans. He received many gifts during his travels and bestowed many, as well. The public came out in droves to see him along rail lines, at train depots and at events in the cities, waving handkerchiefs and climbing on rooftops and lampposts to get a better view. The press followed his every move and reported on what he wore, drank, and ate, how he danced and with whom, while businesses used his name in their advertising and offered new products with a Russian flavor. He was one of America’s first celebrities and the fact that he was Russian made him all the more interesting and exotic.

The story of the Grand Duke’s trip is more than just a tale of forbidden love, political intrigue and colorful characters. It also touches upon important developments and events in the late nineteenth century, both in the United States and Russia. Alexis’s grand tour coincided with a period of recovery and change in America. While the South bridled under the conditions of Reconstruction, the North also struggled to recover from the effects of the long and bloody war. Newspaper accounts of the Grand Duke’s travels frequently highlighted the ongoing tensions between North and South, particularly in southern states, where city officials were eager to show that they too could host a royal visitor in style. Media reports also reflected Americans’ conflicted attitudes toward royalty, noting the irony, or hypocrisy, of a democratic nation lavishly celebrating the visit of a member of Russia’s royal family. Finally, on the international scene, the United States was embroiled in conflict over the possible annexation of San Domingo and engaged in a battle of wills with England over the Alabama Claims, unsettled disputes from the Civil War that charged England with failure to enforce British neutrality. Though both situations resolved peacefully, the possibility of war had seemed real at various points.

Russia also faced a series of challenges at the end of the nineteenth century. In the decade before Alexis’s visit, his father, Alexander II, had enacted a series of wide-ranging legal and administrative reforms, including the abolition of serfdom. Despite these reforms - which many considered too little, too late - the monarchy continued to be plagued by a growing revolutionary movement that, since the 1860s, had become more radical and violent. It was, in fact, Tsar Alexander II who would become the focus of the revolutionaries’ anger; in 1881, ten years after Alexis’s visit, Alexander II was assassinated, the victim of a terrorist’s bomb. The international landscape was dangerous, as well. The last decades of the nineteenth century saw the birth of new alliances and new rivalries for all the nations of Europe. In particular, Russia faced a Polish uprising, the specter of a newly unified Germany and a hostile relationship with the Ottoman Empire that had turned violent several times in the past and would do so again in the late 1870s. To assert itself in Europe and elsewhere, in 1870 Russia renounced the Black Sea clause that had prohibited Russian war ships in that body of water. The renunciation caused alarm in Europe and America, the greatest concern being a possible war between England and Russia. While the rumors that Alexander was seeking an alliance with the United States were probably untrue, the Tsar certainly viewed the Russian-American friendship as one worth retaining.

The Grand Duke’s visit was significant in other ways, as well. Though much of his time was consumed with ceremonial balls and dinners, there was also an educational and trade dimension, as well. As he traveled from city to city, officials showed Alexis local businesses, industrial facilities and schools, usually as part of the city tour, but often enough, it was the Grand Duke himself who inquired about these things and asked to learn more about American society and industry. Local politicians and businessmen welcomed the chance to show off their city’s most impressive features and, in some instances, held hope for future trade with Russia. Consequently, Alexis toured the naval facilities in New York, Philadelphia, Annapolis, and Charlestown, and stopped at the Smith and Wesson factory in Springfield. In Buffalo and Milwaukee, he visited the grain elevators, in Cleveland the Bessemer Steel Works, and in Chicago he viewed the inner workings of a pork packing factory. In Memphis he inquired about the cotton industry and toured a state of the art penal facility. In some places, he left with gifts and mementos, in other cases he took away samples to be considered by the Russian government for later purchase.

Finally, Alexis toured the United States during a period of historic events and colorful figures. He visited Chicago within weeks of the Great Fire and hunted buffalo with Custer and Buffalo Bill, only a few years before the final decimation of the great herds. He visited New Orleans and was present when the Krewe of Rex parade first rolled through the city streets on Mardi Gras day. He visited New York as the first tower of the Brooklyn Bridge began to rise above the East River and the political ring of Boss Tweed began to fall. He admired the enormous underground caverns of Mammoth Cave and experienced the majestic wonder of Niagara Falls. During his travels, Alexis also met a number of famous Americans, like Samuel Morse, the father of the telegraph; Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, the poet; Cyrus Field, the brain-child of the transatlantic cable; Horace Greeley, the famous newspaperman and proponent of western expansion; Joseph Pulitzer, the newspaper publisher; and, General George Meade, the hero of Gettysburg. Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote and read a poem for the Grand Duke, and Matthew Brady photographed him, as did Brady’s chief rival, Jeremiah Gurney.

The Grand Duke’s visit raised a number of interesting questions for Americans about how they defined themselves as members of a democratic republic and whether that definition precluded the hosting and toasting of royalty. In many places, there were lengthy and heated discussions about whether public funds should be used to host a member of a royal family. Many people, in the press and in private letters, lamented the toadyism and fawning over the Grand Duke, but others were happy to receive him and there were many stories of pressing, eager crowds and competition for ball and banquet tickets. The visit also presented the opportunity for some citizens to comment on other issues, such as the decline of the buffalo herds, the emergence of the ASPCA, and the problem of racism in America.

The most lasting result of Alexis’s grand tour of the United States, however, was its role in stimulating American public interest in Russia. As the first Russian celebrity to travel through the United States, crowds followed Alexis wherever he went, and the detailed press coverage of his every move meant that average Americans, not just those in positions of power, could hope to catch a glimpse of him and could learn about what he wore and with whom he danced in each city. The press satisfied and stimulated this curiosity about Russia with biographies of the royal family and lengthy essays on Russian geography, history, climate and the national traits of her people. Meanwhile, some of the illustrated papers of the day, such as Harper’s Weekly and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated, printed detailed engravings of Russian political figures and scenes of Russian life. Although Russian-American diplomatic relations would cool considerably over the next decades, the American public’s interest in Russian literature, art, music and ballet would grow and continue long into the next century, overcoming the restrictions of politics and opposing ideologies. Alexis’s visit is particularly interesting if we consider the intense struggle over ideology and spheres of influence that would develop between these two nations in the twentieth century. Now, as the United States and Russia find themselves on opposite sides of a variety of issues, it is hard to remember that there was a time when America and Russia were friends.