Maria Ukhvatova holds a PhD in Political Science from the Higher School of Economics. She works as a Junior Research Fellow at Saint-Petersburg State University and a Research Assistant at the Ronald F. Inglehart Laboratory for Comparative Social Research at the Higher School of Economics.

The role of the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) in modern Russian society has seen a dramatic increase in recent years, a trend that manifests in the growing participation of clergy in official government events, including inaugurations.

After the protests of 2011-2012, Russian state authorities recognized their opponents as real threat and began to work on forming a unified ideology that would help unite the population to avoid a “color revolution” or Maidan. The authorities' reaction to mass protests marked a return to what journalist and policy expert Alexander Baunov has called a "conservative-type relationship." The political course of the resulting "revival" of so-called "spiritual staples” became accomplished by enacting a multifaceted program involving, among other measures, the construction of new churches; the tightening of legislation concerning the faithful; and the incorporation of Orthodox leaders into government councils.

The ROC, in turn, shows an interest in exerting its influence on state power. A conservative agenda, including requests for various types of prohibitions addressed to the Church, has become an important part of Russian public policy in recent years. As the sphere of their political and public interests continues to expand, the Orthodox clergy openly presents itself in the role of guardians of order as well as spiritual and moral values.

My recent work investigates the emergence of conservative discourse in speeches by Orthodox clergy. We aim to examine moments where speakers address the protection of traditional values, as well as their attempts to justify authoritarian rule by Russian regional officials. Our sources are regional inauguration events dating from 2012 to 2017, which we considered on the basis of news from the official websites of the regions; full transcripts of the events; and, most importantly, video broadcasts of the events posted to YouTube. Using content analysis, which enables the identification of various factors and phenomena within our chosen texts, we analyzed a total of 79 events. In 31 cases, we managed to find full speeches by clergymembers.

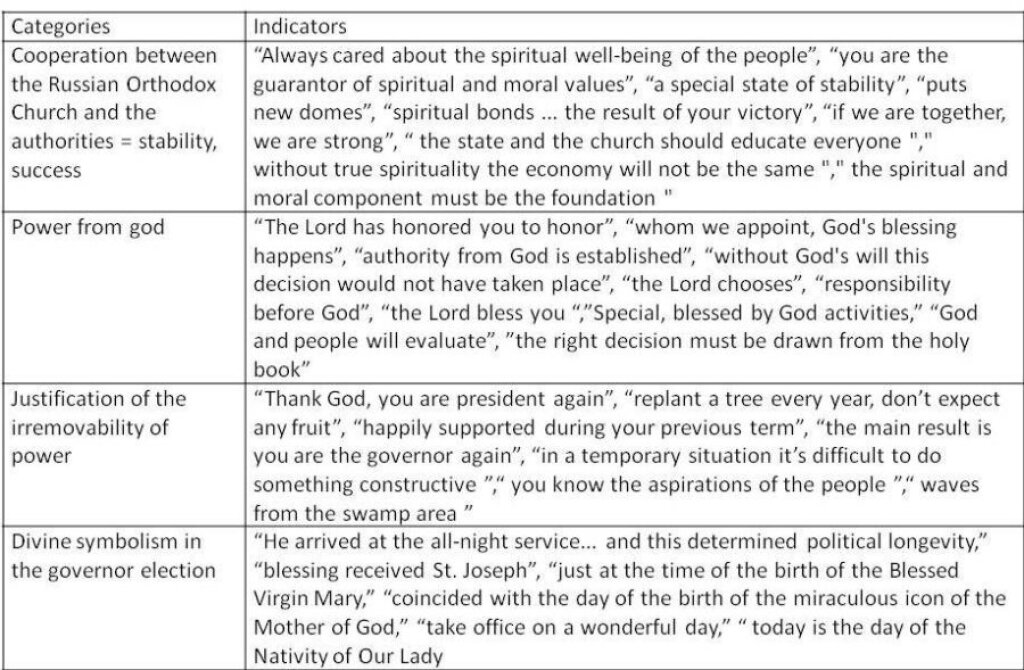

Most inaugurations proceed according to a standard set of rules. First, nearly every ROC speaker reads out a congratulatory message from Patriarch Kirill of All Russia, and then pronounces the words himself. The Patriach's congratulations generally treat moral issues, particularly the importance of spiritual and traditional values. What topics recur within the speeches of regional clergymembers? Using content analysis, we divided all the available texts into four main categories (see Table 1 below).

Table 1 presents categories of analysis of the clergy’s messages at the inaugurations of governors.

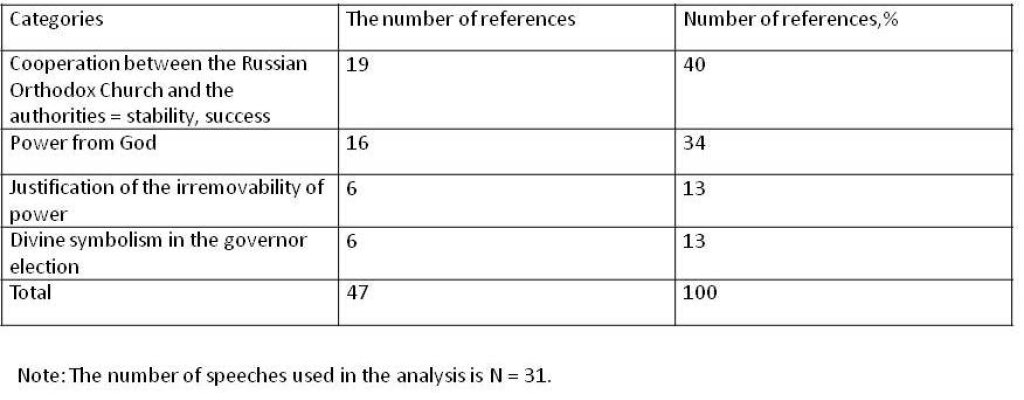

Table 2 presents the frequency of distribution of these categories in the appeals of religious leaders.

The most common category to which religious leaders refer is “cooperation between the Russian Orthodox Church and regional authorities.” This form of "cooperation," according to the ROC, is a prerequisite for the development of society's spiritual and moral state. A strong moral basis, in turn, is said to necessarily lead to the region's economic success, as in the following excerpt from the 2014 inauguration of the governor of Primorsky krai:

Without true spirituality, the economy will not be the same. In general, the economy will turn out poorly. People will steal everything, trade it all away for a bowl of lentil stew. No wonder Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky said: "If there is no God, then everything is permitted."

At the same time, speeches cast governors and other official as guarantors in the spiritual development of society, as in this example from 2017: "You are a guarantor of spiritual and moral values in the life of our people, which brings especial stability to our republic, to our region.” In the same vein, officials will often opine about the type of governor the population most needs: “Here is a governor who builds roads and puts up new churches instead of destroying them. He suits us.”

The second most important category is “power from God.” Orthodox leaders' messaging frequently deploys the theme of power, which is framed as God's blessing: “I will recall the words of Scripture: that authority from God has been established and the head is a good servant of God;” “Without God, this decision would not have taken place. Of course, we all make choices, we all fulfill our civic duty, but God is the one who chooses.” Strength and correct decisions, for clergymembers, must draw on the Bible: “The poor and the rich will come, the poor will come for minimal help, but the rich will think that they always possess pearls. You must always make the right decision, but this right decision must be drawn from such a holy book as the Bible."

The last two categories, which we define as “justifications for the permanence of power” and “symbolism within gubernatorial election discourse” appear in speeches with roughly the same frequency. Clergymembers often attempt to justify the long terms of rule that regional heads enjoy by claiming that incumbents know the problems facing the local population well, and are therefore better equipped to solve them, than a newcomer. For instance, in his message to Governor O.P. Koroloyv — about to be sworn in for the fifth time in 2014 — Metropolitan Lipetskiy said: “As they say — when a tree is replanted every year, don’t expect any fruit.” Religious leaders thus seek to give a positive spin to the governor's long tenure, saying things like, “Thank God you are the president again,” “The important thing is you are governor again,” "It is difficult to do anything constructive in a temporary position."

The most frequent use of the categories we identified was found in the Chuvash Republic, the Republic of Mordovia, the Belgorod oblast, and the Republic of Mari El. These data allow us to draw only very cautious conclusions about the higher frequency of statements in the Volga region and Central Russia. More detailed conclusions would require more presentations in our sample.

We concluded that the rhetoric reproduced by Orthodox clergy reflects calls from authorities to strengthen spiritual and moral values in society and to provide justification for the permanence of power, in particular by bringing in "supporting evidence" from the Bible. The Church sees the success and prosperity of the regions as inexorably tied to its cooperation with the authorities, a cooperation that they frame as necessarily producing a flourishing of the spiritual and moral values that form the foundation of the state. Our analysis did not reveal significant regional variation; on the other hand, our study did show that the Russian Orthodox Church clergy dominates these political discourses when compared with other faiths.

The addresses of church hierarchs highlighted in our study comport in a general way with the conservative turn Russian society has seen since 2012. We have no reason to believe that these speeches required direct coordination with the authorities or that they were written by secular politicians and then imposed on clergy "from above." Instead, we believe that this rhetoric is consistent with the political ideas of the leaders of the Russian Orthodox Church. We can therefore recognize that ROC leaders comprise an important element in modern Russia's conservative coalition.

As a postscript, it is worth noting that the COVID-19 pandemic has produced certain changes in the symbiotic relationship between the ROC and the Russian government. Shuttering churches to avoid viral spread, for instance, led to controversy. ROC officials reacted negatively to the closing of churches for Easter, one of the most important holidays in the Orthodox Christian faith. Clearly, the relationship between state and religious power in Russia is a complex and dynamic one, requiring further investigation.