Ekaterina Chelpanova is a PhD student at the School of Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of Kansas. She holds a Candidatskaya degree from Saint Petersburg State University, Faculty of History, Department of History of the Middle Ages. Her current research focuses on strategies of coping with trauma in postwar Soviet literature and cinema.

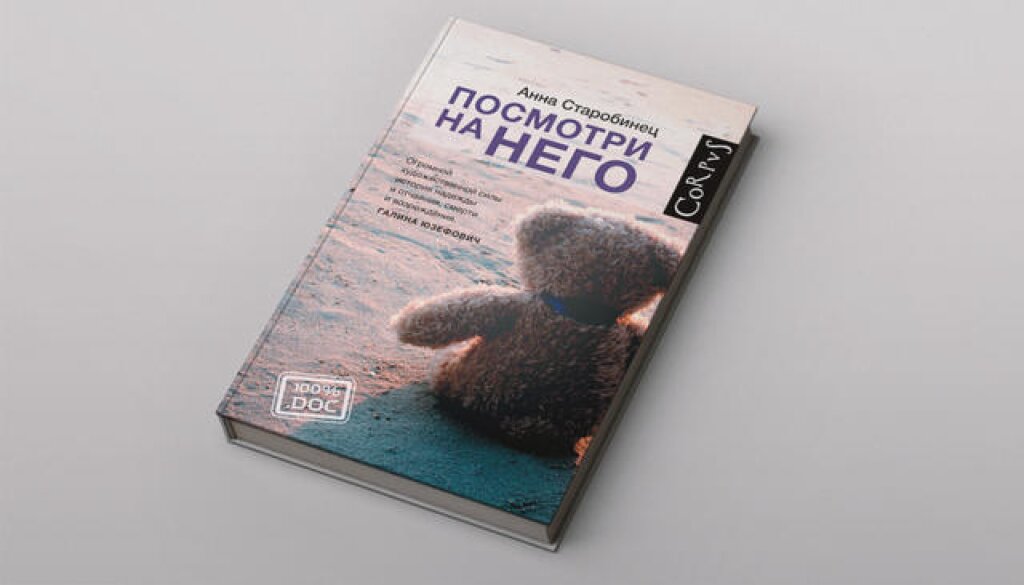

In Russian culture, the writer often acts as a missionary, charting new paths in public discourse by broaching previously unmentionable topics. In 2017, Russian fiction writer Anna Starobinets opened a new chapter in this tradition by describing some deeply personal encounters with the official Russian medical system. Look at Him, a book based on Starobinets' own experience of terminating a much-wanted pregnancy for medical reasons, has already contributed to positive changes in Russian medical practice.

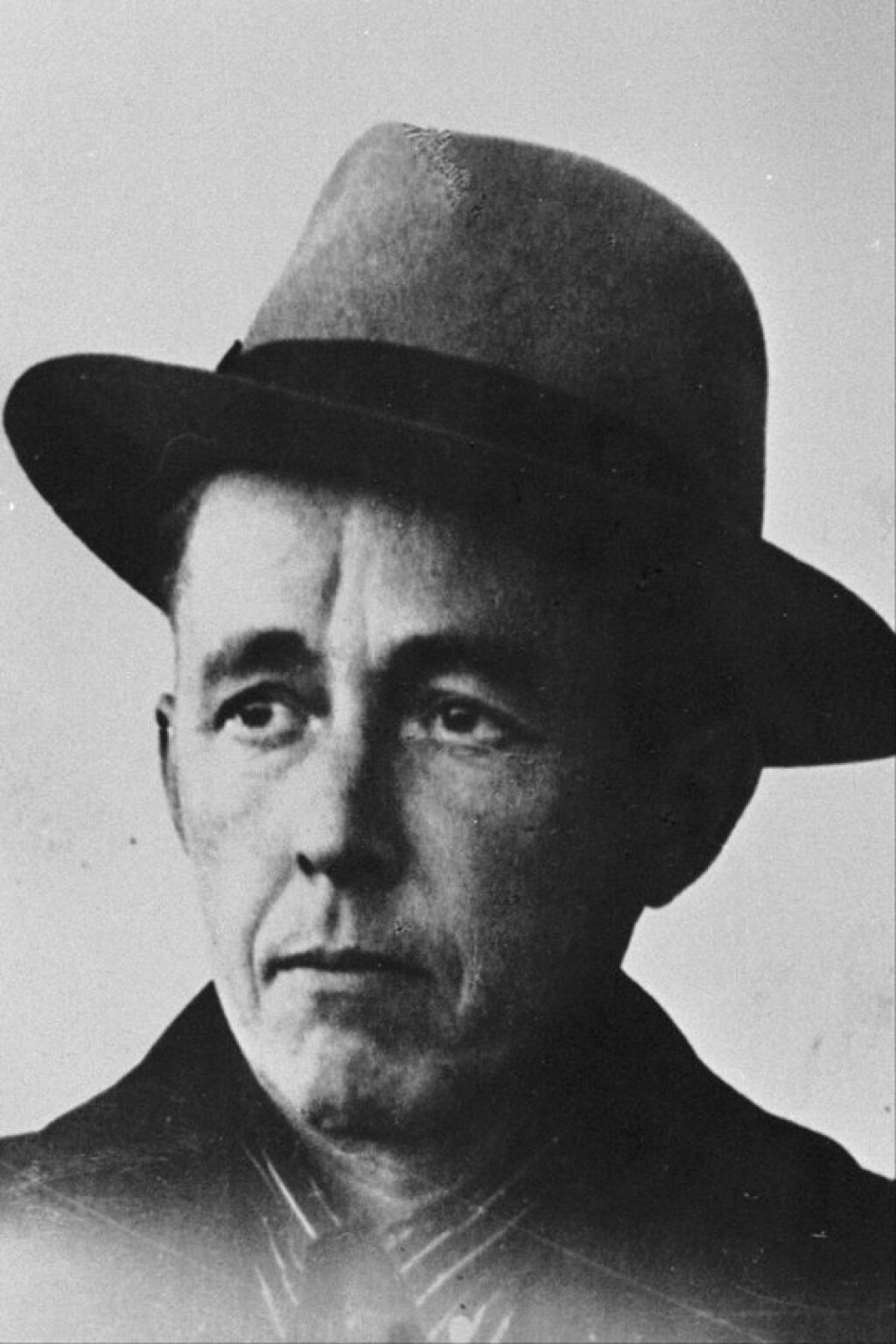

The author's case is not unique, however. In fact, she continues a long-standing tradition of changing the system through literature by unsparingly discussing personal trauma. In 1963, Alexander Solzhenitsyn similarly challenged a taboo — this time, of speaking about cancer — by using his own experience of cancer survival as the basis for the novel Cancer Ward.

Always direct, in Cancer Ward Solzhenitsyn questioned the legitimacy of the paternalistic model of medicine. In this model, which dominated in the Soviet Union, a doctor always knows better than the patient, on the unexamined assumption that the patient is incapable of making informed choices. The doctor decides what is the best with no regard for the patient’s thoughts or concerns: the cure justifies any means imaginable. For Solzhenitsyn, the model of paternalism in medicine reflected the totalitarian Soviet state. In Solzhenitsyn’s view, just as the totalitarian premise conceals the potential to oppress even its enforcers, the paternalistic model of medicine deceives doctors into believing they control their domain. But they are as likely as their patients to become victims of the system, especially when their roles are reversed.

Solzhenitsyn almost never leaves his reader in doubt. His verdict is unequivocal: the state that practices bodily control (even under the mask of healthcare) aims to deprive the citizens of consciousness of self. Yet, paradoxically, Solzhenitsyn shows that a body whose host is deprived of self-consciousness is subject to illness and decay. The novel's protagonist, Oleg, recovers from cancer due not to the treatment he receives, but more because of the high degree of inner freedom he was able to preserve despite all the trials he has been through.

By injecting the personal into the institutional, Solzhenitsyn deepened the discussion of illness and initiated a considerable literary tradition. It is to this area that Starobinets contributes with her unflinching portrayals of intimate life events, including her traumatizing encounter with Russian institutions of neonatal care. An autobiographical perspective in this case imbues the text with a higher degree of reader trust. Following the publication of Cancer Ward, Solzhenitsyn received numerous letters from people battling cancer. Similarly, even before Look at Him was finished, Starobinets was already being inundated with letters from Russian women, which had started pouring in as soon as the first excerpts were published online.

The women who wrote to Starobinets shared their own experiences of going through maternity care, confessing that they were often humiliated by doctors and nurses while giving birth — even when their pregnancies were relatively medically unproblematic.

Taken together, these testimonials suggested that in many Russian medical institutions (including quite well-regarded ones), childbirth is still treated like a kind of female job, almost a contract. Problems with pregnancy or, even worse, the misfortune of miscarriage, are therefore often seen by both doctors and society at large as failure to perform a duty, or a sign of some invisible inner corruption. Anna Starobinets herself provides an explanation: in the Soviet Union, starting in Stalin’s time, giving birth was perceived as a female duty. Just as males had to defend their motherland, women were commanded to give birth to future loyal Soviet citizens. Women unable to perform their "duty" were suspected of being lazy and irresponsible. In old Russian language, a pregnant woman was referred to as neprazdnaya, what literally means “not lazy, performing a duty.” This old word was still in use in Soviet-era villages.

Besides the Soviet background, treating problems with pregnancy as a sign of a female “sin” is rooted in folklore where pain and suffering associated with the birth process were often understood as punishment for sexual pleasure and desire. A woman unable to give birth might become the object of mistreatment from many sides, including her husband and his family. A fascinating novel by the Soviet writer Valentin Rasputin, Live and Remember (1974), depicts attitudes toward a young women in the Russian village of the 1940s. The novel's heroine cannot conceive and consequently suffers many derogatory remarks from her mother-in-law. In one of the episodes, the mother-in-law wishes that her daughter-in-law would “die from worms in the body.”

In traditional village culture, men were not allowed to observe women in labor, while a woman who had given birth was considered to be “dirty” and would remain unclean for forty days. During that “purification period,” she was prohibited from entering the church. Starobinets shows that these folk beliefs are far from extinct in contemporary society. She bears witness to the fact that women experiencing problematic pregnancies are still stigmatized and relegated to complete isolation, even if they have husbands who previously expressed care and offered support. Even in the present day, should a pregnancy present medical problems, it remains "not the husband’s business" to interfere, with society continuing to protect males from painful exposure to the vulnerability of the female body. Starobinets herself sees the impact of folk tradition in this culture of protecting men from female "weakness." She comments, for instance, that advertisements contribute to expectations that female bodies remain perfectly shaped and decorated with expensive underwear and neat clothing. Men are considered incapable of living through the trauma of encounter with female vulnerability. Thus, though the husband of Starobinets’ protagonist comes with her to the public maternity ward, he is not allowed to accompany her inside:

"You can’t enter with men," a gloomy, sturdy man in a gray sweater blocks our way. He is a guard. He protects the region’s maternity ward. He protects it from men.

The title of Starobinets’ book — the imperative "Look at Him" — counteracts the taboo of discussing the problem of women’s humiliation in the course of maternity care. It forces the reader to look seriously at public stigma and contemplate its roots. That Starobinets’ story is autobiographically based gives the book a missionary aspect, a longstanding feature of the Russian literary tradition.

Following the success of Look at Him, Starobinets continued to break other taboos by injecting the personal. After the death of her husband, for instance, Starobinets took to Facebook. She described her most intimate feelings, trying to model public vulnerability in a way that re-imagined it as a moral category. Breaking the convention of social networks as spaces where people represent themselves and their lives as a series of success, Starobinets began posting photos of herself taken in moments of despair or loss of meaning. In addition to documenting Starobinets’ own difficult feelings, those photos are meant to break the conventions about success and power and discover dignity in vulnerability and suffering.