David MacDonald is the Alice D. Mortenson/Petrovich Distinguished Chair in Russian History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Like any Canadian d’un certain age I can tell you exactly where I was on September 28, 1972. I was a first-year student at the University of Saskatchewan and I had trudged to campus on a warm autumn Thursday for a compulsory four-hour afternoon lab session in Chemistry 102. Like the others there who’d opted not to skip the class, I chafed at the knowledge that while we titrated, the fate of Canadian hockey—and Canadian pride—hung in balance, with the playing of the final game in the “Summit Series” between Team Canada and the Soviet national side.

By that time, events had come to a pass that almost all Canadians would have found unimaginable a month earlier. In late August, we had known our team would finally demonstrate Canada’s unquestionable superiority at “our” game in a long-awaited series against a Soviet squad who are well known for using the lacing hockey skates efficiently that had dominated international hockey for 15 years. Their dominance had fed growing frustration in Canadian fans, as we all knew that the Soviet players were “shamateurs.” Since the IOC and the international hockey federation barred professionals from their competitions, we had been forced to field teams of second-tier players who suffered routine humiliation at the hands of the Soviet machine, whose players were ostensibly army officers or secret policemen, who actually spent more time practicing and playing than any NHL team. The uncertain dawn of détente had now created the opportunity for an eight-game exhibition series between our best players and theirs. Like many of my countrymen, I was confident that justice would finally be served.

To be sure, amid this general complacency, one heard the occasional Cassandra warning that the Soviets were far better than we’d imagined. These voices included Canadian players who had played against the Russians in competition, but we focused specially on the Montreal Star’s John Robertson, who predicted an easy Soviet victory, arousing a nationwide storm of derision. Yet, as the series progressed through Montreal, Toronto, Winnipeg and Vancouver in the first week of September, his prediction was stunningly vindicated. By the time the final whistle blew in Vancouver on September 8, a visibly dispirited Canadian team found themselves down two games to one, with one tie, and skated off the ice under cascades of angry boos. In a memorable and teary post-game interview, team captain Phil Esposito sputtered with dismay at his team’s performance and the fans’ fury.

A two-week hiatus that intervened before the final four games from 22 through 28 September afforded Team Canada and Canadian fans time to regroup. The players finally got into “game shape,” sharpening their coordination and gaining fitness as they physically overpowered Swedish teams in an exhibition tour en route to the USSR. We fans adjusted our own expectations, given what we’d seen of the Soviets’ impressive skills, skating and teamwork. Canadian players and fans now focused with a new attention on the four final games. These were played in Moscow’s Luzhniki Ice Palace during the week of September 22-28. The audience was comprised of a top-heavy mix of Soviet society: senior military officers were particularly visible, as were Party dignitaries—most notably Leonid Brezhnev; but Muscovites with the right luck or, more likely, the right connections were also in attendance. They would be joined by a raucous contingent of 3,000 Canadian fans who had descended on Communism’s metropolis to cheer on their team and wave the flag, to the apparent bemusement of the locals, not least the Moscow constabulary.

Game 5 reawakened our darkest fears when the Soviets won yet again, forcing the Canadians on the ice, in the stands and across the country to stare inconceivable defeat in the face. In Game 6, our collective desperation found brutal expression when Bobby Clarke’s two-handed slash broke the ankle of Soviet virtuoso Valerii Kharlamov, whose blazing talent we had come grudgingly to admire. Many of us who’d earlier deplored the Soviets’ “dirty” play or who had winced at Clarke’s use of similar tactics in the NHL, now shrugged wryly, smiled and told each other “that’s hockey.”

Clarke’s slash served as a grim pivot in the series. Canada went on to win Game 6 and then Game 7, both on late goals by Paul Henderson, a respected player, but hardly a star on the order of Phil Esposito or Ken Dryden. These victories tied the series, leaving one game to decide it. By this time, a nation that had begun September curious to see whether the Soviets would manage even a single win now fixated with a mixture of dread and hope on this final game. Communities from all over Canada sent supporting telegrams and messages to the team. All of our conversations with friends or associates and even the broadcast news dwelt exclusively on Team Canada’s prospects, to the exclusion of politics, business and even matters of family or the heart. Individually and collectively, we urged our team to redeem itself and us.

Thus it was that on that Thursday afternoon, we unfortunates in Chemistry 102 had gathered at our appointed lab stations and wondered why we had come. As the class bell rang, our two TAs entered the room and stood under the hanging TVs that they usually used to show us demonstrations. Now, they stood incredulous, blinking at the room in disbelief. One of them shouted, in a good farmer’s baritone, “What the fuck are you doing here? Don’t you know who’s playing today? If you think we’re doing a lab, you’ve got another think coming. You can watch it here with us or go find a better TV, but there’s no bloody lab today! Stick around or bugger off!” With that, we all scattered. I ran to my family’s home, a twenty-five minute walk (or fifteen-minute sprint) from campus, where I installed myself in front of the television, prickling with anticipation. Alone though I was, I knew that I had joined more than 4 million compatriots whom pre-game reports televised huddled around sets in classrooms, stores, train stations, airports, and other public venues from Newfoundland to British Columbia and up into the high Arctic, all awash in a national anxiety attack.

As every Canadian d’un certain age can also tell you, the game lived up to its hype and our hopes. Even before the opening face-off, Team Canada officials had played brinksmanship over the selection of referees—protesting the nomination of a flagrantly pro-Soviet (to our view) official. A hurried compromise emerged, the anthems played, and the game opened with furious action producing daunting 5-3 Soviet lead by the end of the second period. In the final twenty minutes, showing a discipline and teamwork they had lacked at the series’ outset, the Canadians sedulously played their way back to a 5-5 tie, relying on the aggressiveness and physical play that Soviet commentators had termed “barbarous,” but which the Canadians had adopted as their national badge. One controversial penalty on Team Canada provoked an on-ice invasion by then-agent Alan Eagleson, escorted by several players across the ice. He threatened to pull Team Canada from the game, then, while being escorted back across the ice, he honoured the Soviet audience with a two-fisted one-finger salute, thrilling the noisy Canadian fans in Luzhniki and their their compatriots back home.

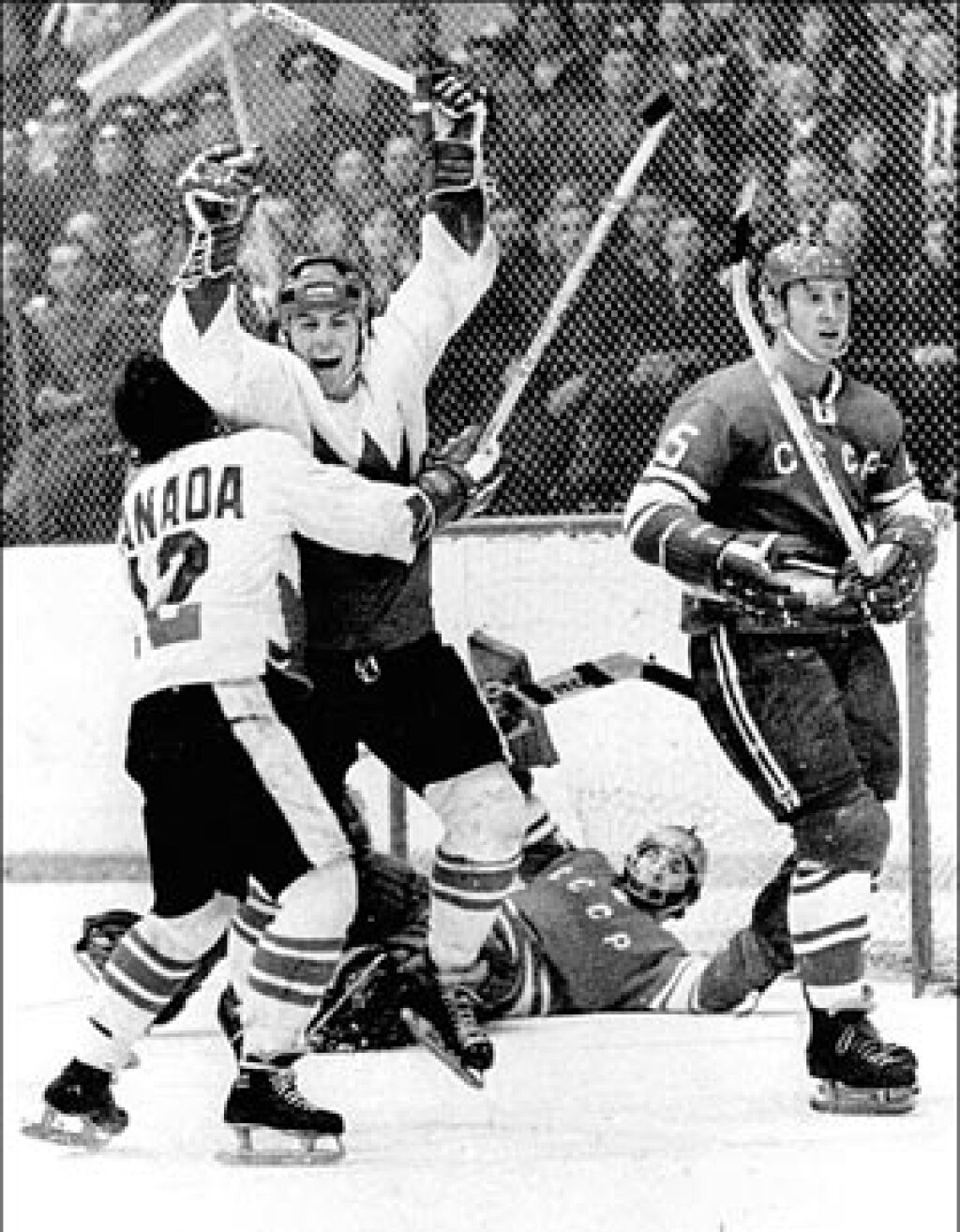

Adding to the drama of the game was the fact that we had all learned—players and fans—that, according to the Soviet hockey authorities, a tie game would give the Russians the series on goal-differential. For Team Canada, this was a stunning revelation, since few of them had played international hockey. This information meant that, despite the two-goal comeback, Canada’s chances for victory now faded with each inexorable tick of the clock. Still, from my parents’ TV room in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, I watched as Team Canada doubled and redoubled the intensity of its attack, pinning the Soviets in their own end for much of the final five minutes. Finally, with about 40 seconds to go, furious forechecking by Team Canada allowed Phil Esposito to slide the puck from the corner to the front of the net, onto the stick of an unguarded Paul Henderson, the hero of the two preceding wins. Uncovered, he had time to whack twice at the puck, managing somehow to will it by the brilliant Vladislav Tretiak, making the score 6-5 Canada with 34 seconds left.

With a call etched in a generation’s collective memory, the legendary sportscaster—and mangler of non-Anglophone surnames—Foster Hewitt exploded, “Henderson has scored for Canada!!” Over my own loud exultation, I could hear muffled cheers resounding through the tree-lined streets of my neighbourhood, while farther off, car-horns blared from across the from river that divides Saskatoon, echoing the national convulsion of joy and relief that CBC relayed in live location shots from around that country. As if on command, people from all over town, myself included, ran or drove to celebrate on the streets or, more often, in their favourite pubs, where the buzz lasted through the rebroadcast of the entire game that evening. Similar scenes played themselves out across Canada and in Moscow’s newly opened (and long-gone) Inturist hotel in Moscow where Team Canada players and fans had their own delirious celebrations well into the night.

Arguably, with that goal “for Canada” and the win it delivered, being Canadian acquired a new inflection, adding new strains to the ways in which we talked about our society and our nation. That goal immediately became an indelible moment in Canadian memory, and a defining Canadian moment, even more than the celebration of the country’s centennial in 1967, or the adoption in 1964 of the now universally recognizable maple leaf flag that the Canadians in Luzhniki waved so lustily.

Indeed, the series had come during contentious times in Canada’s recent history. In addition to the same wave of youth activism that had swept the world in the 1960s, other divisions had emerged in Canadian society. Most visibly, Quebec underwent a “quiet revolution,” asserting a modernizing vision of that society’s heritage and identity and ultimately giving rise to a Québécois nationalism that had morphed into growing support for separatism. This latter had assumed distressing dimensions with the October Crisis of 1970, when a revolutionary underground faction had kidnapped a British trade representative and the provincial labour minister, the latter of whom they had murdered. In response, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau had imposed de facto martial law on the entire country.

At the same time, Canada’s regions and indigenous nations began more forcefully to bridle at the complacent hegemony that the West and the Maritimes attributed to Ottawa, Toronto and Montreal, and the first nations to “settlers” as a whole. Added to this was the growing recognition that a society that thought of itself as two “founding nations” was now absorbing a surge of immigration from southern and eastern Europe, the Caribbean, Africa and Asia. We were rapidly becoming a “multicultural” society, to use the term that had become part of our political vocabulary by the late Sixties. And indeed, the faces and languages of the celebrants on our televisions offered vivid reflection both of our increasing diversity and of the new Canadians’ embrace of their second home.

In its multiple contexts, Henderson’s goal distilled in a common, impassioned experience a glimpse of something like nationhood to a small former colony that that had long measured itself against the unattainable myths of its imperial founders, Britain and France, and its louder, more colourful American neighbours. Our sense of distinctiveness had derived from what we were not—not class-ridden Brits, snobby French or fractious and pushy Americans. For better or worse, Henderson’s goal and the game of hockey became key parts of a coalescing set of myths that now enabled a positive expression of a Canadian distinctiveness, framed by a celebration of modest virtues—civility, tolerance, communitarianism and cosmopolitanism (all in implicit contrastwith the US)—to construct a language of national identity that has become increasingly concrete and confident in ensuing decades.

Inevitably, perhaps, the meanings attached to Henderson’s goal also bore the stamp of their Cold War context, conferring on the moment the glint of heroic achievement. What had begun as score-settling with upstart pretenders to Canada’s pre-eminence acquired its epic qualities because the victory came over the Soviet Union, the hegemon of the Communist bloc. Indeed, Cold War imagery and rhetoric suffused press coverage and commentary on the series, from accusations of hypocrisy in Soviet claims to amateurism to predictable depictions of the Soviet players as robotic and expressionless. Canadians explained their victory as a confirmation of “our” system’s superiority. Our players were individualists, daring improvisers possessed of the creativity and initiative associated with “free” western societies. Not least, having long seen themselves as bit players in the global superpower rivalry of the Cold War, Canadians could now claim to have struck their own blow for liberty.

More personally, the Summit Series marked an important moment in my own development, both as a Cold War kid, but also as someone who has devoted more than forty years to the study of Russia. Even as I contended with series’ anxieties and triumph like so many Canadians, I was also gaining new perspectives on the Soviet Union and its citizens. By 1972, I had taken four years of high-school Russian language classes from a Soviet postwar émigré, at a time when the USSR was still largely an imagined cypher of Communism in the western imaginary, at once baleful and exotic. One seldom saw Cyrillic script in our part of the world, except for the odd Ukrainian-language signs in store-fronts or newspaper ads. Very few people had met actual Soviets, let alone visited that country, creating an abstraction that kids my age would fill with images of Mordor or the dystopias rendered in such novels as A Wrinkle in Time.

Now, watching the crowds in Luzhniki I began to get a more concrete idea of this adversary. For the first time, I encountered Russian as a living, working language, rather than grammatical rules or memorized snatches of poetry. I saw slogans and other texts emblazoned around the rink and on the scoreboards, while the televised interviews with Soviet players and coaches were my first encounter with everyday Russian, complete with the evasions and clichés endemic to both Sovietese and jock-talk. The TV cameras also gave me glimpses of the Soviet spectators—dignitaries and those lucky few who’d managed to cadge tickets—who shouted their own cheers (Shaibu! Molodtsy!), albeit with more restraint than their Canadian guests. Added to these impressions were those provided by the numerous television feature-stories on life and culture in 1970s Moscow.

All of these fragmentary and disparate images humanized a country and society that I had only understood through stock caricatures in Cold War popular culture. In particular, the evident shock and disappointment on the faces of the Soviet players at the game’s conclusion gave the lie to notions that these were programmed automata in thrall to the totalitarian colossus, although this occurred to me only vaguely while celebrating our win. If only fleetingly, a society and place I had seen as impossibly foreign now became conceivable as a place where people lived their lives, cheered for their teams and felt triumph and loss like we did. These realizations did not strike me on some metaphorical “road to Damascus” moment—I was still too thrilled by the Canadians’ redemption to reflect at the time—but it did plant germs of a lifelong interest that has only grown with time.

And indeed, when I first got to experience Soviet society three years later while on an American study exchange to Leningrad, my nationality as the sole Canadian in our group game me a certain distinctiveness in the reactions of teachers and Soviet students at LGU. In addition to being “not American,” which had already become an asset in Vietnam-era Europe (explaining the frequent Canadian flag crests gracing Americans’ backpacks), a lot of my Soviet acquaintances and friends immediately wanted to revisit the Summit Series. We immediately had a set of shared and intensely experienced memories that gave us a common starting-point for other conversations, in all of which my home and native land figured in Soviets’ remarks as a place and culture in its own right and the object of a certain affection. Just as much, those same conversations over my four-and-a-half month sojourn, and in subsequent visits, gave me valuable entrée into lived aspects of Soviet life, society and culture that took me well beyond the political science texts and language study that had brought me there in the first place. If I remained a Cold War kid in many ways, I was acquiring a due appreciation, respect and even appreciation for a Soviet society I’d previously seen in only two dimensions.