This is Part I in a two-part series. Part II will follow on Friday, 9/11.

Yaraslava Ananka is a research assistant at the Department of Slavonic Studies of the Humboldt University (Berlin, Germany).

While different practices of reconstructive appropriation are at work in Russia today, the dominant feature of contemporary Ukrainian identity discourses is alienation. On the political level, so-called decommunization is pursued: cities and streets are renamed, while Soviet heraldry and symbolism are removed and banned. All these sanctioned measures often turn into spontaneous iconoclastic actions, among them the demolition of Lenin monuments five years ago.

In the dismemberment and decapitation of monuments, the anthropomorphism of the destroyed object itself can be just as important as the act of destruction. In the process, the emphasis shifts from destroying existing symbolic-iconic signs to the previous creation of artificial, human-like figures of substitution and projection. Anthropomorphism brings performative magic — mimetic mediality — into play. Vandalism, in other words, becomes voodoo.

Be it vandalism or voodoo, such performances operate with material objects. But what about Russian idioms and icons that cannot be destroyed in the here and now? How can one erase all the phraseology-based mnemotopoi and memes present in post-Soviet identity due to literature, not to mention Soviet popular songs and movies, that are continuously and deliberately revitalized by the Russian mass media?

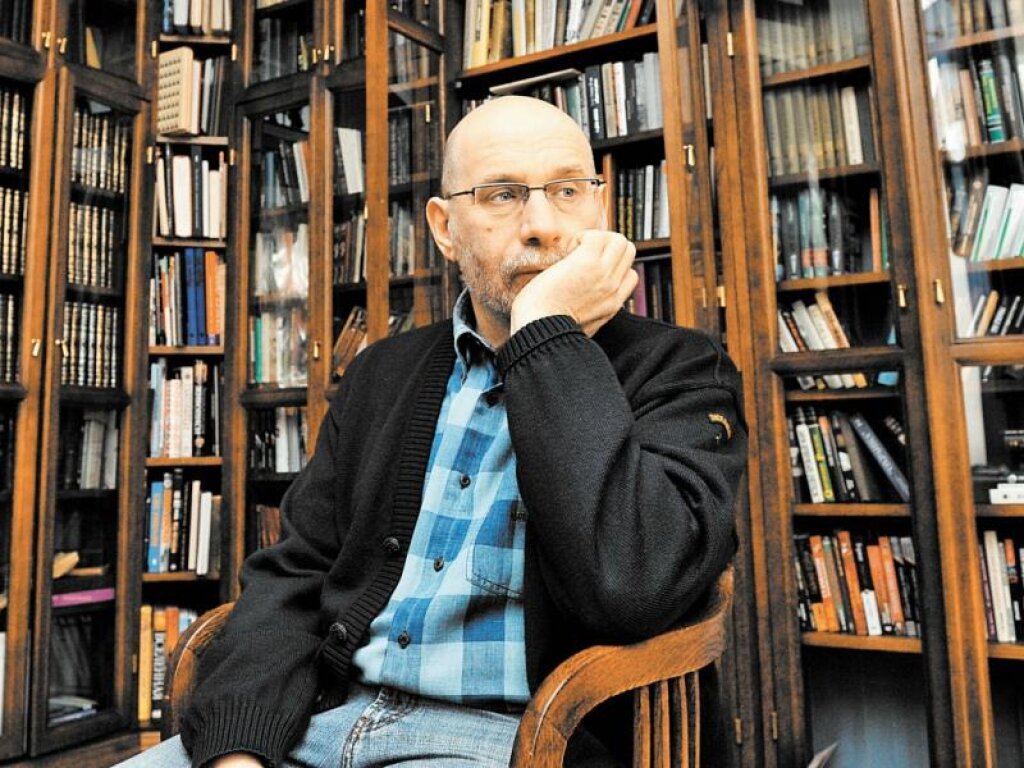

The protagonist of this essay, writer, actor, documentary filmmaker and singer Antin Mukhars’kyi, stands precisely for such meta-medial art. One of the most controversial partisans in the forest of Soviet symbols and icons, Mukhars’kyi performs several projects simultaneously. The best-known of these, “Soft Ukrainization” and “Hard Ukrainization,” are presented by Mukhars’kyi under the heteronym Orest Liutyi (Orest the Grim). He describes himself as a singing professor of anthropology who deals with the Homo sovieticus.

In what follows, I will discuss his clip Katia-Vatnitsa. It is a song based on three poems by Ukrainian poet and permanent Orest co-author Artem Polezhaka. Part I will briefly analyze the visual and audio context of the clip, which parodies Russian discourses on Ukraine. Part II, to follow this Friday, will address in greater detail the Russian intertexts of this bilingual song.

Besides the first name "Katia," the song's title contains the designation vatnitsa. This is the feminine form of vatnik, a pejorative slang name for radical Russian patriots who long for the USSR and welcomed the Russian “repatriation” of the Crimea.

With its frame chronotope of puppet theater, the clip declares its multi- and meta-mediality. The stage opens with applause. Among the dolls and toys we see Orest Liutyi in a folkloristic embroidered shirt (vyšivanka). These introductory images (0:10–0:53´) are a reference to the opening credits of the late-Soviet children's TV program Visiting a Fairy Tale (V gostiakh u skazki) and, in general, to the expositions of Soviet fairytale films.

The clip visualizes the set phrase “rasskazyvat’ skazki” (“to tell fairy tales”) in the meaning “to lie.” In brief, it is pitched as a fairy tale about the ways in which propaganda fairy tales are pitched. But first, Orest Liutyi asks questions in the form of didactic riddles, to which, as an experienced pedagogue and anthropology professor, he has (or should have) answers. The central question is “Where do vatniki come from?”, which intentionally recalls the prototypical "children's" question of “Where do babies come from?”

The clip rejects the traditional euphemisms that normally answer this question: “they are brought by a stork or found in the cabbages.” Indirectly, however, another question comes to the fore: who are the parents, literally, the generators of the vatniki, why are there so many of them, and what is wrong with them, with these dehumanized puppets, toy soldiers, demonized zombies and vampires?

The rhetorical question of where vatniki come from is eventually answered, albeit not in words. Instead, the answer lies in the musical track accompanying the opening credits, which is the melody of the song Podmoskovnye vechera (Moscow Nights) stylized to the soundtrack of the show Visiting a Fairy Tale. Thus, the clip geographically and politically locates the reproduction of vatniki in Moscow and historically and culturally in the Soviet past. It also reveals the mechanism of the cloning, since the melody of “Moscow Nights" was a crucial auditory element for the Soviet radio station Maiak. The melody sounded at the beginning of every hour before the news.

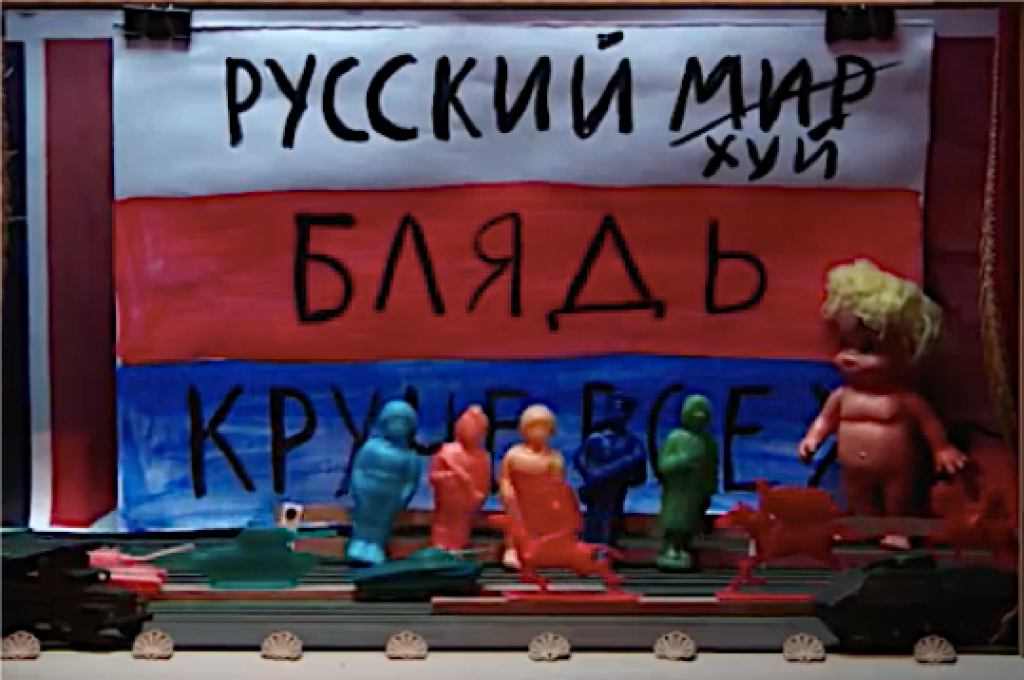

In addition to TV and radio, the video also addresses other idiomatic media, like posters. The majority of these Russian-language posters contain official billboard slogans that decorated the streets in Russia and Crimea five years ago. The video defamiliarizes these slogans through the techniques of meme-hack and adbusting, modes of graphic vandalism that decode political or advertising posters by adding new inscriptions or drawings. In our case, this vandalism takes the form of four-letter words and obscene caricatures of genitals.

The special “sacrilege” of this guerrilla communication can be seen in the fact that the posters were allegedly drawn by children. But here, the video also doesn’t "tell fairy tales," so to speak: in 2014, there were numerous local and federal competitions, and exhibitions, of patriotic children's drawings on the occasion of the Annexation of Crimea.

Here, obscene language becomes the most important speaker-revealing feature of the Russian language. The defamiliarized slogans on the children’s drawings correspond to the speech patterns of the clip's main character, Katia. Similarly, as the children’s drawings celebrate the return of Crimea and at the same time abuse “the evil Ukrainian fascists,” Katia's hate speech combines various mottos of Soviet nostalgia with extensive cascades of swearing.

The scene of Katia’s hysterical squabbling with her Ukrainian opponent (4:02–5:00´) is also a fairly accurate allusion to Russian political talk shows, which since 2014 have been devoted largely to the Ukrainian theme. Scenic and rhetorical, these programs are also based on communicative sabotage and trolling: a pro-Ukrainian expert is usually invited to the studio, so that, during the show, each of his or her replies can be interrupted and shouted over by presenters, other guests, and the audience.

The clips not only parodies particular content from these broadcasts, but actually quotes them directly. Highlights include the fake reports of a boy crucified by Ukrainian soldiers (4:50–4:56) and the threats of Russian TV presenter Dmitry Kiselev, who noted that Russia could, if it chose, turn the US into a pile of radioactive ash (4:19–4:21´).

But the most important quotation in the whole discourse is the magic formula “Krym nash” (“Crimea is ours”) (0:50–0:54´; 1:32´), which, in the clip's script, rhymes with “puskat’ v tirazh” (“to duplicate”). The multiply reproduced slogan “Krym nash” is a very economical and therefore poetically-ideologically very effective phrase. It is a minimal sentence of two syllables or lexemes. The first, “Krym,” is a calling card for private nostalgia and collective revisionist revenge, while the other, “nash,” is a collectivist possessive pronoun possessing the semantics of imperative appropriation. “Krym nash,” then, is a performative password to be chanted, a motto, a mantra. And so we end up at the Word.