Andrei Zavadski works at intersections of memory studies, public history, media studies, and museum studies. He is currently a research associate at the Institute of Art and Material Culture, TU Dortmund University, Germany, and a co-editor-in-chief of The February Journal.

Ksenia Robbe is a senior lecturer in European culture and literature (Russian) at the University of Groningen, Netherlands. She works at the intersections of the postcolonial and the postsocialist, and memory and time studies.

Material in this post was previously published in Studies in Russian, Eurasian and Central European New Media. It is reprinted here with permission of the publisher.

The world has changed so dramatically in the past four years that the 2020 Belarusian protests against Aliaksandr Lukashenka and his regime seem several lifetimes away. But the memory of this social movement lives on and might feed the protest memoryscape within Belarus—and perhaps beyond.

Understanding this memory requires a complex analysis of the protests and the participants’ protest imaginaries, as well as of the events that followed. This work has already begun, and we contribute to it by examining references to the past events and periods that were invoked during the protests. Put differently, we are interested in the mnemonic practices exercised at the demonstrations, which, we argue, add to the emerging “collected” memory of the 2020 events.

Among a multitude of symbols, slogans, and memes that constituted the demonstrators’ protest imaginaries, there were numerous historical and cultural references: to the Belarusian People’s Republic of 1918, the political violence of the Soviet era and the Stalinist purges, the Holocaust, and the 1990s. In our recently published article, we explore protesters’ mnemonic practices related to the perestroika and the 1990s (“the long 1990s”), seeking to understand how demonstrators used references to this historical period to produce meanings and evoke affects.

What aspects of “the long 1990s” are recalled? How do protesters reiterate slogans from the 1989-1991 protests across the Soviet space, or use forms of protest that were developed or popularized thirty years ago? Do the Belarusian protests include cultural references to the 1990s beyond specifically protest repertoires? How do they reframe or shift the meaning of well-known symbols, slogans, and practices?

We answer these questions by examining posters and banners, video recordings, and media reports linked to the protests. Our analysis leads us to identify at least three functions of the mnemonic referencing of the 1990s.

The 1990s as the closest antecedent

The first function is recalling the 1989-1991 mobilizations as the closest antecedent to “(un)failed” attempts at resisting authoritarian regimes. The year 2020 saw by far the largest episode of civic unrest in Belarus in recent memory, comparable to the upheavals of thirty years ago. The civic activism of 1989-1991 across the Soviet Union served as a repository of repertoires for contemporary Belarusian protests. References to the events of this period were thus a symbolic return to the most recent significant political upheavals, in the sense of “picking up where we left off.”

Notably, the 1990s have a generally ambiguous image in post-socialist societies. Many people see them as a time of political breakthroughs and attempted or partially realized democratic agendas, but also, particularly in subsequent decades, as a period of compromised hopes and betrayed opportunities for democratic transformation. It is this combination of inspiration, partial success, and eventual failure, typical of memories constituting the imaginaries of protest movements, that has inspired the 2020 mnemonic return to an earlier moment of resistance. The 2020 protests saw invocations of symbols of the 1989-1991 protests, re-use of their slogans, as well as practices of re-enactment that re-performed memories of revolt and civic disobedience.

One example here is a poster addressing Lukashenka that reads “C’mon, turn Swan Lake on’ (Vkliuchai uzhe Lebedinoe ozero)” (Image 1). Held by a young woman, this poster refers to a key symbol of the 1991 anti-democratic coup—and the successful resistance to it—during which all TV channels in the Soviet Union broadcast a performance of Piotr Tchaikovsky’s ballet as thousands took to the Moscow streets. In the cultural memory of August 1991, Swan Lake has come to stand for the “swan song” of a disintegrating regime and its helpless attempts to hold on to power by resorting to violence.

The 1990s as a relay

The second function is remembering the 1990s as a mnemonic relay for re-experiencing and re-engaging past struggles. This type of invocation refers to a time of national revival in newly independent Belarus (through the employment of pre-Soviet national symbols) and of public use of dissident discourse and anti-fascist rhetoric. More specifically, references to these times act as a stage or an experiential space for practicing hope—personally experienced, or easily imagined, by contemporary protesters.

Protesters appealed to a sense of national unity by using the white-red-white flag and the Pahonia coat of arms—both symbols of the Belarusian People’s Republic (1918) that were reintroduced as the official Belarusian flag and coat of arms during the early post-Soviet/ pre-Lukashenka period (1991–1995), but which Lukashenka later outlawed. The effect of these symbols was amplified through frequent performances of the song “Pahonia,” written in 1916 and considered a possible national anthem in the early 1990s. Both the flag and the coat of arms are thus inherent in the remembrance of the 1990s.

To invoke the flag and coat of arms (Image 2) is to subvert historical myths dating to the period after 1995, the year of the referendum that signified the return to an updated version of symbols belonging to the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic, and a way to re-experience the pre-1995 political process.

The 1990s as a rediscovered past

Finally, the third function of referring to the 1990s is to return to a rediscovered past––a (forgotten) time of freedom and improvisation. Posters and performances bringing popular culture repertoires of the 1990s into the political present––often invoking memories of that decade’s newness, experimentation, and sense of global openness––were major sources of positive references based on shared and mediated experiences. This form of positive memory, with its upbeat tone, responds to the starkly negative framing of the decade in Lukashenka’s discourse.

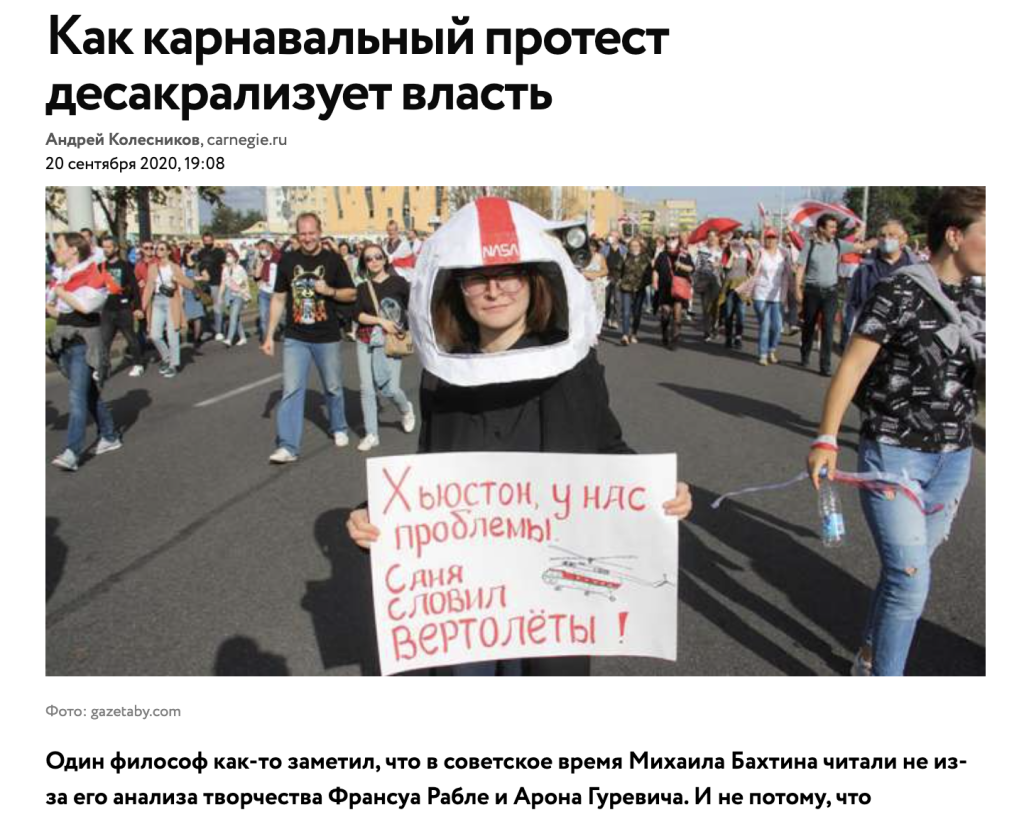

Protest posters in this vein employed characters and memes from 1990s-era popular culture. One example is the presentation of Lukashenka as a ghost hunted by “ghostbusters” (Image 3). Another is a poster with the inscription “Houston, we have a problem. Sania [Lukashenko] has gone cuckoo” [H’iuston, u nas problemy. Sanya slovil vertolëty!] (Image 4). The poster refers to the phrase popularized by Apollo-13, a 1995 American blockbuster that has since then become the source of multiple memes.

A post-Soviet protest memoryscape?

We conclude our article by asking whether it is possible to speak of an emerging post-Soviet protest memoryscape. At the time of our writing in 2021, this seemed possible due to transgenerational (for instance, activism of the (grand)parents’ generation) and transnational (activism of people in other parts of the former Soviet Union, including Russia and the Baltic states) aspects of the mnemonic references analyzed.

However, as we finalized the article in 2022, after the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine—which has also involved the use of Belarusian territory—we felt very pessimistic about the emergence of such a memoryscape across the region.

And yet, despite the violent events since the start of this new phase in Russia’s war against Ukraine, the region’s protest memoryscape has continued to feed on 1990s-era references. One example is the Swan Lake graffiti photographed in Saint Petersburg in March 2022 by participants of Alexandra Arkhipova and Yuri Lapshin’s No Wobble project, as part of their research into Russian citizens’ silent protest against the war.

Another example comes from a demonstration commemorating Alexey Navalny that took place in Berlin in February 2024. In the photo, participants display a banner with the slogan “Our hearts demand change (Peremen trebuyut nashi serdtsa).” These words refer to Viktor Tsoi’s 1989 song, “Khochu peremen (I want change),” an important political symbol of perestroika. The slogan, as well as the song itself, were extensively used during the 2020 protests in Belarus, the 2011-2012 protests in Russia, and more.

Whether these symbolic returns to the 1990s signal, or make possible, the emergence of a protest memoryscape in countries of the former Soviet Union requires further research. But if we could try to imagine a future after the current war, memories of (some of the) post-Soviet transformations might still prove helpful for re-building connections across the region.