The Jordan Center stands with all the people of Ukraine, Russia, and the rest of the world who oppose the Russian invasion of Ukraine. See our statement here.

Tara Wheelwright is a PhD Candidate in Slavic Studies at Brown University.

In Russian culture, everyday material life, byt, stands in contrast to the spiritually meaningful existence of life, bytie. Byt represents everyday routine, the smallest details of daily life, whereas bytie inhabits a lofty spiritual position within the Russian intellectual tradition, existing between everyday life and “real” life. Written in 1995, Ludmila Ulitskaya’s Medea and Her Children merges byt and bytie by portraying the spiritual satisfaction found in the everyday.

I read Ulitskaya’s novel a few years ago, before becoming a mother. As a student, the weight of both byt and bytie appeared trivial, outmatched by the anxiety of deadlines and impending exams. Yet passages from the novel remain consistently lodged in my brain, images I conjure when laundry seems endless, crumbs of toddler-decimated meals accumulate under my feet, and the never-ending list of essential errands screams for my attention over the more simmering, slow-burn bellow of academic errands.

Juggling work and life as a woman or a parent is not new terrain. However, a recommendation, if I may: Medea and Her Children will not increase the chances your child gets moved off a waitlist for the ever-elusive spot in daycare, but it may lower your blood pressure as you find a sort of “here and now” bliss within the everyday routine of life. And spoiler alert, I am a devoutly renounced Catholic atheist, so a call for religion to solve your woes this is not.

A bit about byt. At the turn of the twentieth century, the Symbolists transformed the meaning of byt from merely describing daily life to a shorthand for the routine and material, a daily existence devoid of spiritual, artistic, or revolutionary transcendence. The transformed significance of byt continued to develop from a neutral term to one with more negative connotations, eventually suggesting a corrosive banality that threatened higher, often intellectual, aspirations.

The everyday is often overlooked but remains fundamental to survival, which is necessary to achieve the intellectual aspirations of bytie. Official Soviet ideology considered a preoccupation with the everyday unpatriotic, subversive, and even anti-Soviet, leaving women in a difficult position where they were considered simultaneously crucial to the success of the Soviet project and secondary in terms of their needs and wants.

Paradoxically, as Benjamin Sutcliffe notes, women were said to reign over the domestic arena in order to allow men to dominate the public arena and pursue the highly prized bytie, while simultaneously denouncing byt from a distance. The post-Stalinist years saw a complete reversal of the view of women and byt that had been proclaimed after the Revolution, with women urged to participate in the everyday because it complemented men’s pursuits in the public domain.

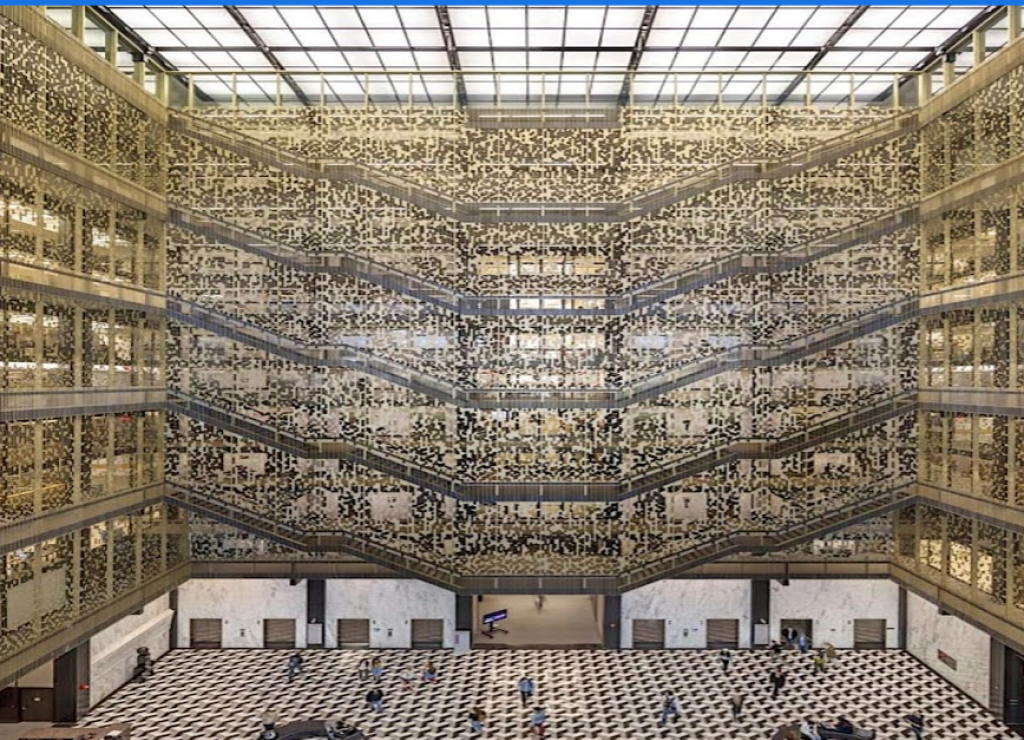

Above: A communal Soviet kitchen

In Ulitskaya's Medea and Her Children, Medea infuses her everyday life with a sense of spirituality, privileging orthopraxis over orthodoxy. The routines of everyday life are not burdens that add to the chaos of the day. Instead, everyday life in Medea and Her Children follows routines that share a greater similarity with religious rituals.

A slightly odd routine had long ago been established in the house: they usually had supper with the children between seven and eight, put them to bed early, and then came together again in the night for a late meal which was as bad for the digestion as it was good for the soul. Now, at a late hour, having finished numerous chores around the house, Medea and Georgii were sitting in the light of the oil lamp and enjoying each other’s company.

Within these accepted routines, there is a greater emphasis not on the rituals and dogmas of religion, but on a type of spiritual serenity from focusing on connections to other individuals in daily life.

Medea’s family is not connected merely by blood, but instead spans several generations and many different cultures, bringing in people “from all these tribes from Lithuania, Georgia, Siberia, and Central Asia.” Her kin are not all biologically related to her, which creates a family united out of desire rather than just necessity. Due to this, byt becomes a welcome part of “family life” rather than a draining chore done under obligation.

On her way to visit an old friend in Tashkent, Medea catches a ride to the train station in Rostov. After the men drop her off, she realizes

why the cloth with the daisy pattern had seemed so familiar: it was her own curtain, which she had given to Nina […] thirty years ago […] the young men were the children of the girl whose burn Medea had treated that night. Medea smiled to herself and felt reassured. Despite being so much more crowded and having so much more hustle and bustle, the world still functioned in its old way, the way she understood, with small miracles happening, people coming together and parting, and all of it forming a wonderful pattern.

Family in the world of Medea and Her Children expands beyond biological connection, creating an interconnected network of people from different geographical and cultural spheres. Family, along with the structure of religion, act as two points of stability within the narrative. What seems to emerge, then, is a revival of pre-Revolutionary spirituality that emphasizes the private over the public, and a desire to erase the cultural divisions that emerged during the Soviet era, in which the government classified people as either ethnic Russians or “others.”

However, one aspect of Medea’s combination of byt and bytie extends to a loftier place than routine or humanity: the serenity of nature: “The heavy mood of her journey, which she had seemed to be carrying on her shoulders," the narrator writes, "was washed away by the gentle waves of the morning breeze.” It’s in these moments that I, personally, find the spiritual power of the everyday at its strongest. Ulitskaya’s descriptions of cooking, laundering, and cleaning are offset by the power of nature’s ability to freeze a moment and direct attention to a world above and beyond material drudgery.

This is a spiritual power meant in the most secular way possible. It is spiritual only in that it literally raises the focus from toil and the sticky underfoot minutiae of life to the greater world: Fold the laundry and bask in the warmth of the sun on your face, Ulitskaya seems to recommend. Of course, if that does not soothe, you can always switch tactics and take a page from Frank Costanza with a yell of “serenity now!”