Joy Neumeyer is a PhD candidate in History at the University of California, Berkeley and current Visiting Scholar at the Jordan Center who writes about Russian society and culture.

In “Five Spoons of Elixir,” a story written by science fiction duo Arkady and Boris Strugatsky in the early 1980s, a writer stumbles upon the secret to immortality. Methusalehn, a mysterious potion, is guarded by the 500-year-old chairman of the local Communist party committee. He offers to let the writer join the society of immortals, if only he will keep their secret.

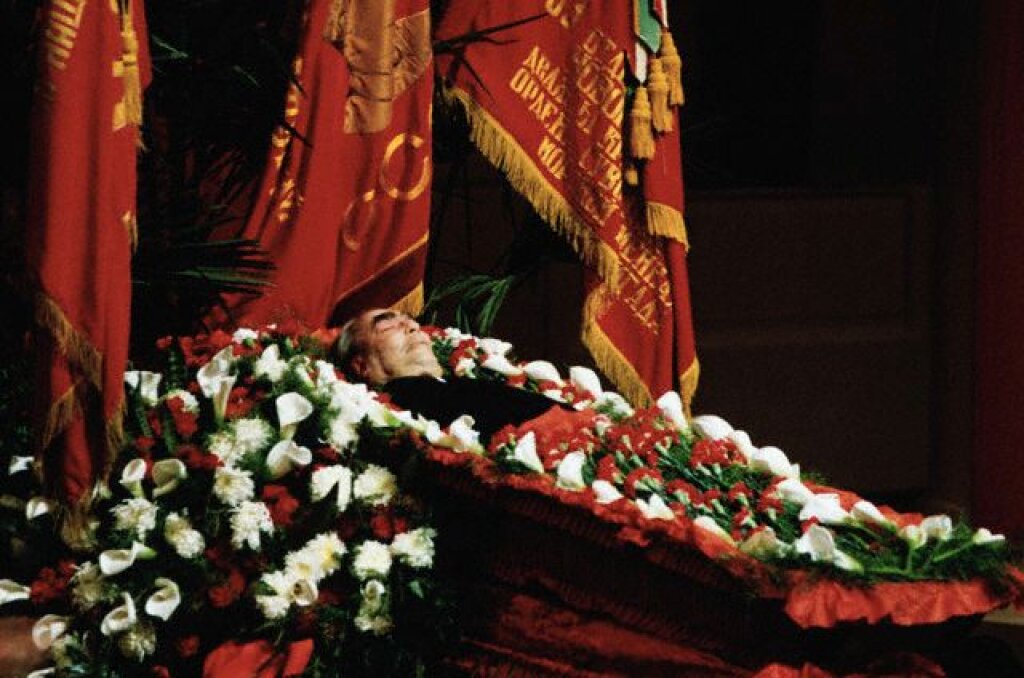

From the mid-1960s, as life expectancy in Russia caught up to that in other highly developed countries for the first time, Soviet health and science journals proclaimed that socialism had a unique ability to extend human life. Spurred on by biomedical research in the field of gerontology, science fiction offered hopeful visions of transcending biology and time. Meanwhile, popular health literature encouraged individuals to take collective life extension into their own hands through diet and exercise. The perpetually regenerated General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev, who was revived several times from a state of clinical death, embodied late socialism’s claim of life extension through science.

However, the era’s spirit of preservation was overshadowed by annihilation. In Moscow, the wildly popular actor and singer Vladimir Vysotsky imagined himself as a wolf cornered by hunters, a horseback rider galloping off a cliff, and a corpse witnessing its own funeral. Village prodigal son Vasily Shukshin created existentialist films and short stories about marginalized men in search of meaning, while painter Viktor Popkov depicted loneliness and loss among dying old women. In the Eastern Bloc, ailing pop star Anna German performed mournful love songs before leaving the stage in search of religion and alternative healing. By the early '80s, all these figures were dead, leading to the conflation of their own deaths with those of their doomed heroes.

My dissertation, “Dying Empire: Visions of the End in Late Socialism,” explores the proliferation of death in the Soviet cultural imagination during the long 1970s and its relationship to the demise of the state. While the profusion of death in Russian culture during glasnost and after the collapse is well-known (and studied in marvelously gory detail in Eliot Borenstein’s Overkill), my research reveals the roots of this phenomenon in late socialism. I show how expressions of madness, malady, and despair flourished in mass culture and were seized on by fans, who reached out to cultural figures and mourned their passing as a way to articulate anxieties about personal and social ailments.

In today’s United States, the '70s seem close at hand. After Donald Trump’s election to the presidency, Foreign Policy asked if the country was once again facing “the geopolitical malaise of the 1970s.” Such comparisons reached a fever pitch during Trump’s impeachment trial, when Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi griped that at least Nixon had the dignity to leave office. Back then, cultural commentators warned of The Death of Progress and The Promise of the Coming Dark Age (the titles of books published in 1973 and 1976, respectively). As American capitalism and Soviet socialism competed for global hegemony, both societies were plagued by fears of decline amidst geopolitical and economic shifts, and both cultures were full of alienated characters in search of regeneration. In Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, Travis Bickle dreams of clearing the scum off the streets while driving around New York City after dark; in Venedikt Erofeev’s novel Moscow to the End of the Line, Venichka fantasizes about his Soviet Eden as he rides through Moscow’s outskirts in a vomit-stained train car.

Major problems of that decade continue to shape the world we inhabit today: among them, exhaustion from failed imperial wars, alarm over the human impact on the environment, and the apparent instability of truth in an age of mass media. The era’s heroes, too, feel all too familiar. Joaquin Phoenix just won an Oscar for his starring role in the Joker, a bitter spectacle of violence that adapts Scorsese’s antiheroes from Taxi Driver and The King of Comedy for the age of the Internet troll.

Cultural despair is generative, feeding longings for wholeness and renewal that ultimately foster a new order. Fritz Stern traced a particularly dark potential outcome of this process in The Politics of Cultural Despair: A Study in the Rise of the Germanic Ideology. The book’s 1974 foreword framed the West as gripped in the throes of a revolt against modernity similar to the one that had elevated the Nazis to power. Others, however, have offered more optimistic readings of despair. Walter Benjamin embraced fixation on loss as the key to political transformation. Valorizations of melancholia are now commonplace in critical theory (and mocked by Slavoj Žižek, in “Melancholy and the Act”).

In the Soviet case, the cultural ferment of the ‘70s was catalyzed during perestroika, when the lamentations that had been circulating in the culture were unleashed on the political stage. The younger generation took up the mantle of embracing death and radicalized it, with music, films, and visual art that staged the disintegration of the social body. In the lyrics of rocker Yegor Letov, even the immaculate Lenin was now said to be “totally dead, decomposed into mold and honey.” Visions of death and redemption would help shape the breakup of the Soviet system and the solutions that seemed available in response.

As socialist dreams of triumphing over time dissolved, others reemerged to take its place. In April 1991, Zdorov’e (Health) magazine published an advertisement from Moscow’s Bible Mission encouraging readers to celebrate Easter. “There is no death!” it announced. “Christ, who through his suffering on the cross defeated death, gave those exiled from paradise eternal life!” As Benjamin understood, the feeling of loss is endemic to modernity; the question is what we make of it.