Anya Bernstein is Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Harvard University. Her first book Religious Bodies Politic: Rituals of Sovereignty in Buryat Buddhism was published in 2013 by the University of Chicago Press. Her current project explores the interstices of religion, technosciences, and future-oriented fantasies through an ethnography of the contemporary transhumanist movement in Russia.

On December 2, 2014, a shake-up occurred at the online journal Russian Planet. Investors fired Pavel Prianikov, the editor-in-chief, prompting several members of his team to leave in solidarity. In a colorful if surreal dialogue, one which commentators deemed worthy of a satirical comedy of the eighteenth-century Russian playwright D. I. Fonvizin, Eduard Eidin, the new editor-in-chief, explained that the reason for this shake up was that the site failed to “reflect” Russia as a “sovereign nation, a Russian civilization.” Claims to insufficient reverence toward Russian culture are nothing new given the many recent editorial changes and closings of other liberal publications, yet Eidin’s comments stood out. Specifically, Eidin charged that Prianikov’s team did not properly engage the work of famous Russian Cosmists on the pages of Russian Planet, as originally contracted.

The late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century thinkers who later became known as “Russian Cosmists” proposed an original rethinking of the relationship between humanity, nature, and the cosmos. Through a unique combination of scientific and occult ideas, this group of rather diverse philosophers and scientists advocated a meaningful, human-directed evolution, technological transcendence of space, time, and the body, mastery of nature, settlement of the outer space, and even the resurrection of the dead.

Prianikov and his team were, in Eidin’s words, “very weak Cosmists” (Kosmisty vy, rebiata, slabye).

The expression “weak Cosmists” (slabye kosmisty) immediately grew into an internet meme, with bloggers producing another, even more popular meme of “not-Cosmist-enough” (nedostatochno kosmist). It was noted that if Prianikov was “not-Cosmist-enough,” Putin was apparently more than sufficiently qualified for this title (dostatochno kosmist), since in his recent presidential address to the Federal Assembly he extensively quoted Ivan Ilyin (1883-1954), a conservative Slavophile émigré philosopher, who, for some reason, was called by the independent liberal TV station Dozhd’ “the main Russian Cosmist.”[1]

An even more obscure reference buried in the middle of Putin’s speech provoked further hermeneutic exegesis. Interpretations of Putin’s address by the liberal media revealed the following phrase: “We all want the same thing: well-being for Russia. So the relations between business and the state should be built on the philosophy of the common task, partnership, and equal dialogue” (emphasis added). Decoders of Putin’s mystical messages at Gazeta.ru immediately picked up on the fact that The Philosophy of the Common Task (Filosofiia obshchego dela) is the famous title under which followers of the actual “founding father” of Russian Cosmists, Nikolai Fedorov (1828-1903), posthumously published his collected works. Slon.ru followed up, quipping that given Putin’s love for the works of Russian philosophers, he “might as well have declared the resurrection from the dead the next national project and thrown all the country’s resources towards this virtuous cause.”

But, so far, Slon.ru concluded with a sigh of relief, “it seems that we been spared.”

The Common Task

Indeed, if Putin were to apply the project of resurrection, as originally envisioned by the eccentric nineteenth-century polymath known as the “Socrates of Moscow,” no one would have been spared. According to Nikolai Fedorov, a founding figure for the Cosmist intellectual tradition, humanity’s ultimate goal, the “common task,” is to use technology to overcome death and resurrect everyone who has already died. Such a resurrection, he argued, is not only an act of love and compassion for the ancestors by their descendants but an ultimate act of “filial duty.” A defining feature of Fedorov’s project is precisely its collective but also totalizing character: no one would be excluded, and no one would have the option to remain dead.

Fedorov’s work has been described as alternately Christian, scientific, occult, and socialist, as he combined his (rather unorthodox) Orthodox Christian beliefs with seemingly secular aspirations. His project of resurrection was technological and materialist, consisting of a physical reassemblage and putting together of pieces of dead ancestors on the subatomic level of anticipatory science. Naturally, this reassemblage would require colonizing other planets to accommodate this growing population—an idea that particularly appealed to the revolutionary sensibility of the first decades of the twentieth century with diverse scholars and artists proclaiming the need for humanity to take its destiny in its own hands. Death, of course, needed to be abolished without delay.

Cyborgizing the Nation

Given this history, liberal journalists were perhaps justified in sighing with relief. Indeed, there are no signs of Putin showing much interest in the “common task” of immortality (personal rejuvenation, perhaps, and not just Botox). Yet somehow, as online cartoonists have joked, the President might just have a stake in the development of regenerative medicine in order to extend his life in four-year increments just in time for the next term of office.

And yet Slon.ru journalists were perhaps too quick to heave a sigh of relief, as, cartoons and Putin aside, immortality as the new national idea has quite a few contemporary champions. In 2011, a former media tycoon and now the founder of a corporate joint venture Immortality (Bessmertie), Dmitry Itskov launched Russia 2045, a sociopolitical movement designed to promote ideas of radical life extension, as well as to lobby the Russian government to adopt the project of uploading consciousness into robotic bodies as a unifying “national idea.” Itskov wrote letters to the then-President Medvedev and then, oddly, enlisted Hollywood actor Steven Segal to write a letter to Putin, offering to declare the pursuit of immortality as the new national idea. In his Avatar Project, Itskov has set the goal of creating a series of progressively changing and improving cyborgs, first melding man and machine, but eventually—in the most radical proposition—eliminating the very need for a physical body, anticipating recent sci-fi flicks on AI and “mind uploading,” such as Her (2013) and Transcendence (2014). The New York Times recently covered this project at length, interestingly, in the Business section.

Other Russian transhumanists—a broad name for an international cultural movement that aspires to “upgrade” the human and improve the human condition by eventually eliminating death itself—consider Itskov’s project too speculative and perhaps too imbued with quasi-religious aspirations that they think run counter to the presumably secularist spirit of the movement. Instead, they offer concrete steps to immortality: by signing a contract with Kriorus, the only cryonics company outside the United States (and the first in Eurasia), one can freeze one’s body in liquid nitrogen while awaiting future reanimation. When I last visited them in the summer of 2013 as part of my fieldwork on Russian transhumanism (see Bernstein forthcoming), they had 27 frozen people; the list of cryonized people has since expanded to 40. A related but separate group, a political party called Partiia prodleniia zhizni (Life Extension or Longevity Party), declares that life extension can only be achieved through cutting-edge science and biotechnologies, lobbying the government to invest in the “right” kind of science (most recently, Party activists, who happened to be in transit from Moscow to California to attend a conference on rejuvenation biotechnology, stopped by the White House to demand more funding for anti-aging research).

A New Eurasianism?

While it is unlikely that Putin is proposing universal resurrection as the new national idea, and there are both pro- and anti-Putin factions among Russian transhumanists, an interest in Russian Cosmism might be one thing they indeed share. Yet Cosmism continues to confuse broader Russian publics. Is it something related to the renewed interest in the space program, which itself has recently been proclaimed to be the new national idea? Is it one of these wacky, semi-mythical Soviet science projects? Or is it a nationalist movement, indeed, a new Russian idea? A few days after the Russian Planet debacle, Afisha, a Moscow entertainment magazine, ran a “Five-Minute Primer on Russian Cosmism,” claiming that while the “original” Cosmists, however extravagant their ideas, were “far from the questions of nationalism and state-building,” now Cosmism is an “alternative version of Russian Orthodoxy, autocracy, and the nation (narodnost’).” “Real” Cosmists, they proclaimed, wanted to “get to the promised land. . . without nationalities, borders, and border patrols. . . They thought about planet Earth and about humanity, without worrying about sovereignties and territorial ambitions.”

In some sense, they are, of course, correct. “Cosmic philosophy,” by definition, can only have cosmic significance. Yet, if one actually delves into Fedorov’s dense prose, peppered with occult references, it is easy to see that Russian messianism, the central role of Russia, Russian Orthodoxy, and autocracy are all important elements of Fedorov’s utopia of universal resurrection. As scholars have demonstrated, Fedorov’s roots lie not only in his fascination with reconciling science and religion, but also in contemporary Western occultism. Fedorov’s philosophy differs from that of Western occultists of his time (such as du Prel, Blavatsky, Besant) precisely by the fact that while having strong Orientalist inclinations, the latter were not commonly interested in particular nationalisms (Hagemeister 1997, Laruelle 2012). Fedorov, on the other hand, developed complex theories about the “manifest destiny” of Russia in Eurasia, as well as Russia’s potential role in India and China (which included China’s conversion to Russian Orthodoxy).

Is Cosmism then becoming a new Eurasianism? On the one hand, it wouldn’t be surprising if Cosmism was shored up by the Kremlin to strengthen national identity, similar to what happened to Eurasianism in the 2000s. On the other hand, there are strong objections from the conservative circles, linked specifically to the questionable “Russianness” of Russian Cosmism. Dugin, for example, back in 1992, pointed out the “suspicious” convergence between Western occultist doctrines and Russian Cosmism. More recently, Orthodox theologians critiquing contemporary transhumanists linked them to Fedorov, whom they consider a heretic, and denounced the idea of human-directed evolution. In a similar vein, an Orthodox cleric recently called Cosmism “Russia’s own brand of secular immortalism,” a dangerous and Western-oriented (globalistkii) trend.

In the meantime, the “weak Cosmist” Prianikov called Cosmism “an original quasi-philosophical idea,” which might be the only thing that Russia ever “gifted to the world.” According to him, it is “the last Russian utopia” (he even identified “The Last Russian Cosmist,” that designation going to the contemporary writer Vladimir Sharov).

Strikingly absent from these discussions are fedorovtsy—Fedorov’s contemporary followers who might be the only ones to accept his teaching whole-heartedly. As I went online to the website of the Fedorov’s Museum-Library in Moscow run by this group, I was startled to learn that while the Cosmist wars raged in the Russian blogosphere, philosopher and scholar S. G. Semenova (1941-2014), the leader of the Fedorov Movement, who was instrumental in rescuing Fedorov’s legacy from obscurity in the 1980s, passed away on December 9, 2014.

As for the bitter rhetorical extremes of “Cosmism as Slavophile Totalitarianism” and “Cosmism as Western Secularism/Playing God,” both liberals and conservatives might gladly accept the “Vanishing Cosmist” trope, joining it with the likes of vanishing noble savages, shamans, and other unruly things.

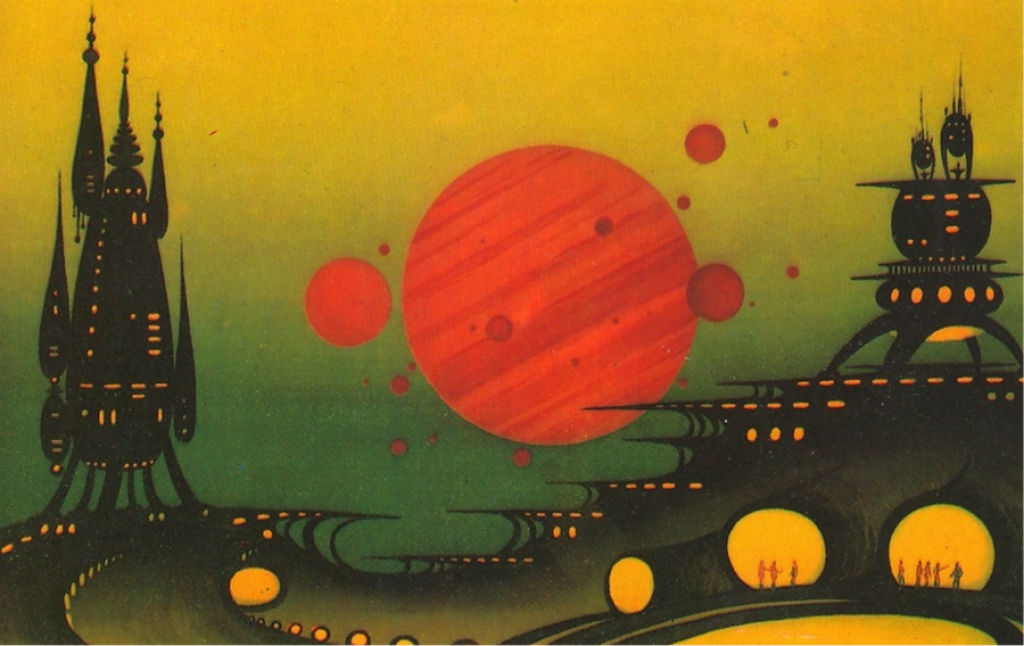

But then again, Cosmism seems to have dropped the “Russian” part and has gone global. Far from disappearing, it is the latest “thing” in the Euroamerican futurist discourse, a “practical philosophy for the posthuman era.” As the cover of “A Cosmist Manifesto,” written by the Brazilian-born American artificial intelligence researcher and author Ben Goertzel and covering topics, such as “AI, nanotechnology, immortality, and psychedelics,” says, “The Cosmist perspective is shown to make plain old common sense of even the wildest future possibilities.” A gift that keeps on giving, indeed.

[1] To my knowledge, Ilyin does not belong to the Cosmist philosophical tradition. It seems that Pavel Lobkov of the Dozhd’ TV station might have confused him with Fedorov, as in the same interview he erroneously ascribes Fedorov’s Philosophy of the Common Task to Ilyin.

References

Bernstein, n.d. “Freeze, Die, Come to Life: The Many Paths to Immortality in Contemporary Russia.”

Hagemeister, Michael. 1997. “Russian Cosmism in the 1920s and Today.” In The Occult in Russian and Soviet Culture, pp. 185-203. Bernice Glatzer Rosenthal, ed. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Laruelle, Marlene. 2012. “Totalitarian Utopia, the Occult, and Technological Modernity in Russia: The Intellectual Experience of Cosmism.” In The New Age of Russia. Occult and Esoteric Dimensions, pp. 238-259. Birgit Menzel, Michael Hagemeister, Bernice Glatzer Rosenthal, eds. Munich: Otto Sagner.