Oksana Nesterenko is a visiting scholar at the Jordan Center for the Advanced Study of Russia at NYU. She received her PhD in Music History and Theory from Stony Brook University in 2021.

“This story is about the crisis of the world’s last remaining idealists,” Andrei Tarkovsky once said of his film Stalker (1979). “Even if it contains moments of despair, it still raises above them. It’s a story of destruction, which leaves the viewer with a sense of hope, because of the catharsis that Aristotle describes. Tragedy purifies man.”

For the majority of listeners, Stalker is not the first cinematic association that comes to mind when they experience Alfred Schnittke’s Concerto Grosso no.1 (1977). (The music in Stalker was composed by Eduard Artemyev.) Yet in his book, Alfred Schnittke’s Concerto Grosso no.1, Peter Schmelz suggests that Stalker’s themes of time’s fluidity, nostalgia and hope are enacted in the piece.

A German-Jewish composer living in the Soviet Union, Schnittke (1934-1998) was a leading figure in an unofficial music scene comprised of composers who did not conform to the Socialist Realist aesthetic and whose works were not performed in official venues until the 1980s. In the West, he is now most famous for his theory and practice of polystylism — a musical idiom that allows for a wide range of historical and contemporary musical styles, including jazz, rock, and serial music, to be incorporated into a single composition. Is this postmodernism? As Schmelz demonstrates, some Soviet critics would not agree.

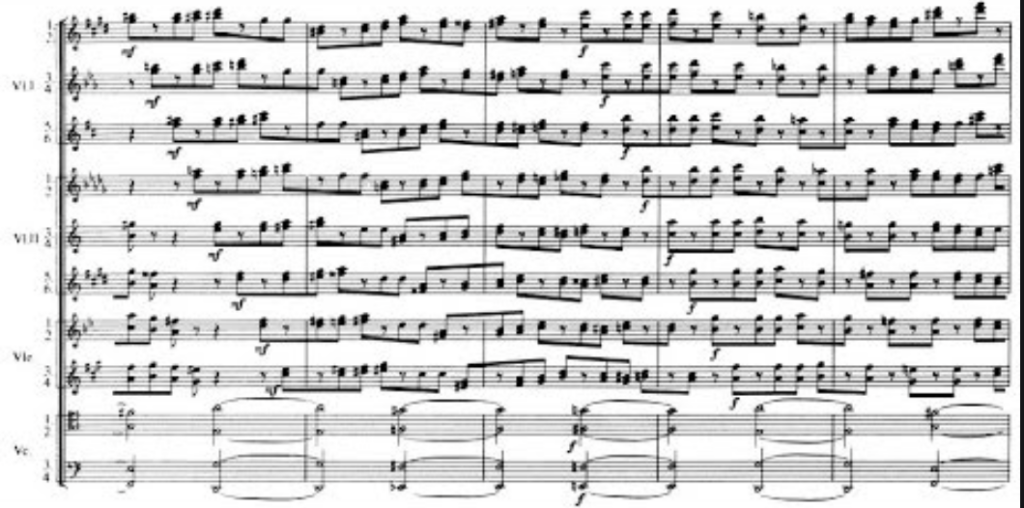

Concerto Grosso no.1 draws on five of Schnittke’s own film scores — for Andrei Khrzhanovsky’s cartoons Glass Harmonica (1968) and Butterfly (1972), Elem Klimov’s Agony (1974), Alexander Mitta’s The Tale of the Moor of Peter the Great (1976), and Accent (1976) by Larisa Shepit’ko — alongside references to the music of Corelli, Bach, Mozart, Tchaikovsky and Schoenberg. The piece also includes a waltz and a tango, which Schnittke’s grandmother’s “great-grandmother used to play on a harpsichord.” The themes metamorphose, collide and “traverse their own paths of destruction,” somehow still producing an organic unity.

It is the destruction of the quotations “in a dissonant, all-encompassing maelstrom” that some critics underscored in Concerto Grosso no.1. To others, the work sounded ominous and macabre, as though foreshadowing a catastrophe. Yet having learned about its composition process, as well as its reception at home and abroad (then and now), and read about Schnittke’s other concerti grossi (he wrote six), his symphonies (he wrote almost nine) and the influence of the piece on “serious” and “entertaining” culture, the reader is compelled to believe that the composition’s recollected memories “signal not destruction, but redemption, paralleling the anticipated redemption of the Room in Stalker.”

Schmelz also explores various views about the work’s postmodern qualities, which allows readers to reflect on the idea of postmodernism in late soviet culture. In the late 1970s, German critics disapproved of Concerto Grosso no.1 as an example of postmodern arbitrariness and eclecticism. Schnittke himself was imagining “a utopia consisting of a single style where fragments of serious music and fragments of music for entertainment would not just be scattered in frivolous way, but would be elements of diverse musical reality.” This emphasis on unity spurred some Soviet critics to reject the idea that polystylism in music, as exemplified by Schnittke’s work, was a postmodern phenomenon. (Some of them, perhaps, did not believe that postmodernism in the USSR existed at all.)

In the sixth and final chapter of his book, Schmelz argues that for some contemporary Russian listeners, Concerto Grosso no.1 represents the past. It is not "abstract" per se, and at the same time is somehow reminiscent of “communal apartments, Soviet circumstances, and the yearning for alternative narratives.” In Black Square, a 1988 documentary about visual art in twentieth-century Russia, the fourth movement from Concerto Grosso no.1 transitions to the fifth as the stagnation of the 1970s leads to perestroika. In between, the poet Yunna Morits describes stagnation as an era of individual resistance against evil — a quality Schnittke represented for many and arguably wanted to be heard in his music.

As Schmelz demonstrates, the composition elicited a wide range of associations in contemporary culture. Many choreographers around the world staged ballets to Schnittke's music, using literary and historical material as varied as Othello, Dracula, The Diary of Anne Frank, Medea, and Don Quijote. Back in Russia, the fifth movement, Rondo, was even performed at the 2014 Winter Olympics opening ceremony in Sochi to accompany the collapse of the Russian Empire leading up to the 1917 Revolution.

Is Concerto Grosso no.1 really about the past? As Schmelz suggests, “Schnittke was consistently drawn to phantoms, shadows, and glimmers of the past in the present.” For some historians and cultural critics, the previous year was a phantom of various challenging epochs from the past. It is probably a good time to revisit this iconic piece of Soviet postmodernism, especially given that an exhaustive guide to its multiple meanings (hopeful and otherwise) is available to today’s reader.