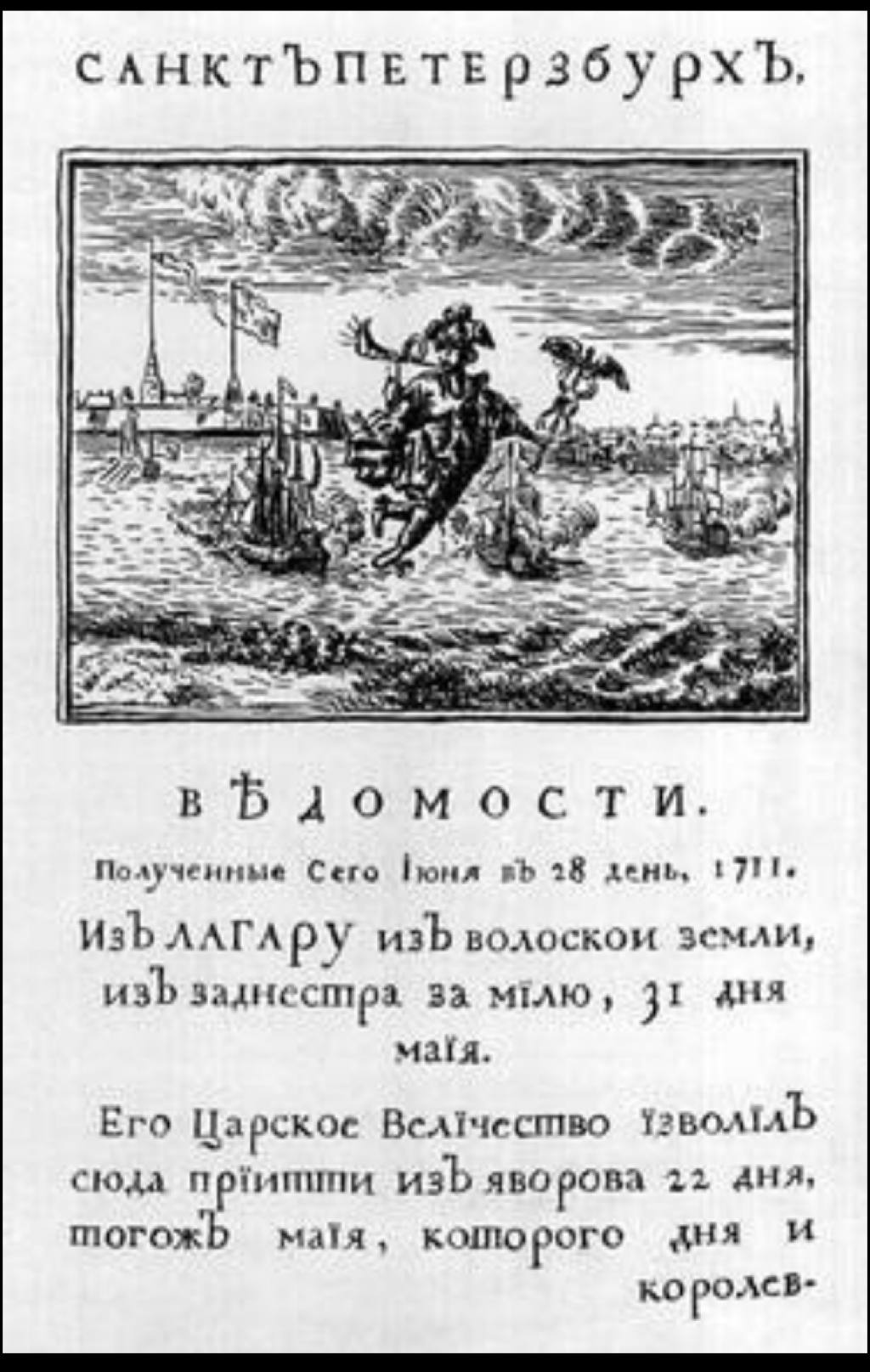

Above: The 28 June 1711 issue of Russia's first newspaper, the Sankt-Peterburgskie Vedomosti

Ala Graff is a Ph.D. candidate in Russian History at the University of Maryland, College Park. She studies the entanglements between press and politics during the late nineteenth century.

Yelizaveta Raykhlina is Adjunct Assistant Professor at NYU Liberal Studies. She is currently working on her first book project, titled The Birth of Imperial Russia’s Commercial Press: Periodicals, Publics, and Social Identity in the Age of Pushkin and Dostoevsky.

Since the collapse of the Soviet regime three decades ago, the Russian press has experienced a revival that transformed it into an important forum for political discussion and debate in Russian society. The rise of investigative journalism, in particular, has made the Russian press a key agent of government accountability.

Yet the threat of political persecution, under which the Russian press has historically operated, has intensified in recent years. Since around 2014, a number of prominent Russian newspapers and media have come under direct or indirect government control (RBC, Lenta, Vedomosti) or have been declared "foreign agents" (Meduza, Dozhd). The 2021 Nobel Peace Prize, shared by Filipino-American journalist Maria Ressa and Dmitry Muratov — the editor of Russia’s prominent daily Novaya Gazeta — brought into sharp relief the importance of press freedoms in Russia and beyond.

The current media landscape, however, reflects certain continuities that have been a feature of Russian press history from its very inception. The study of the contemporary as well as the historical Russian press, therefore, opens up unique vistas for observing Russian governance and the relationship between Russian state and society.

The earliest and most consistent use of the press by the Russian state was to promote the government’s agenda and build popular legitimacy. Russia’s first newspaper, the Sankt-Peterburgskie Vedomosti, was founded by a decree of Peter the Great in 1702 to publicize his modernization projects and to announce military victories.

Despite these efforts to instrumentalize the press to shape public opinion, it invariably served as a platform for dissent and government critique. The short-lived satirical exchanges between Catherine II’s Vsiakaia Vsiachina and the journals of her courtiers skirted the limits of what was acceptable to publish. During the early nineteenth century, prominent literary journals wove together cultural and political critique, creating communities of thought under the strictures of Nikolaevan censorship.

Meanwhile, official newspapers gradually became fora for public opinion. During the 1830s, Tsar Nicholas I unveiled an empire-wide network of official provincial newspapers — Gubernskie Vedomosti — intended to communicate the agenda of the state and to gather information about the empire. The unofficial section of the Gubernskie Vedomosti became a platform stimulating provincial identity and political opinion, as Susan Smith-Peter has shown. When Nicholas I’s successor, Alexander II, undertook the famous Great Reforms of the 1860s, newspapers proved critical in communicating and securing public support for this ambitious program across a geographically, linguistically, and religiously diverse empire.

But the government’s efforts to foster client newspapers were mired in difficulties. Press lords proved to be unreliable partners who did not shy from exploiting the growing dependency of the state on good press. Censorship, on the other hand, came with an unexpected political cost for the government. The technological developments of the 1840s and 1850s — the telegraph and the railways —revolutionized the speed of information-gathering for the press, transforming it into a news powerhouse to rival the state bureaucracy.

During the Bolshevik Revolution, the critical role of the press was underscored by the seizure of printing presses as one of the first acts ordered by the revolutionary leadership. The Bolsheviks knew that to control the press was to control access to information as well as the shaping of opinion and popular support. Throughout the Soviet period and thereafter, newspapers, along with news media like radio, television, and most recently the Internet, have served successive governments as means of projecting their desired image and political narrative.

The press has continuously engaged an ever-greater part of society in political life. But even as it worked to politically inform Russian subjects (later citizens), the press increasingly created a participatory appetite in Russia’s civil society — an appetite the government struggled to control or satisfy. For successive Russian regimes — Imperial, Soviet, and post-Soviet — the tension between the advantages and the perils of an informed society has been a historical continuity.

Over the past half-century, the scholarship on the Russian press has taken several important turns. Trailblazing works in press history, such as those by Charles Ruud and Valentina Chernukha, have focused on the press as an object of government control, regulation, and censorship. Louise McReynolds’s study of the Russian press history in the Gorbachev era focused on the role of journalism in fostering a civil society despite the state's efforts to control it.

More recently, Russian press history has explored new interdisciplinary approaches that both complement and challenge the notion of the press as an object of the state. An edited volume by Barbara Norton and Jehanne Gheith stems at the intersection of press and gender history, revealing that journalism in Imperial Russia was an avenue for women’s career and economic advancement. Approaches from cultural studies by Mark Steinberg and Diane Koenker have produced insightful scholarship on the communal morality and class identity of print workers in Imperial Russia and early Soviet. Pioneering work by Jeffrey Brooks has used methods in social and cultural history to examine literacy, the press, and popular culture across the 1917 divide. Recent revisionist approaches have challenged long standing assumptions about the Russian press as a subordinate of the state. Scholarship by Natalia Patrusheva and Alexandr Kotov has re-framed the historical narratives to reveal patterns of collaboration between the press and the government.

At the moment, the renewed relevance of the Russian press has coincided with a new wave of scholarship in press history. Further advancing interdisciplinary approaches in press history, these works combine the history of Russian journalism with methods from literary and art history, economic history and the history of science and technology. Moreover, new efforts to explore press history in the provinces as well as across the Eurasian space are set to diversify a field long focused on newspapers and journals in Moscow and St. Petersburg.

As press history scholarship reaches out to other disciplines, it also offers a rich source for historical scholarship in virtually any historical field. Scholars from an array of historical disciplines from literary history to the history of medicine, science, and technology will find the press — newspapers, professional journals, and trade magazines — an invaluable primary source on the subject of their research.

Research opportunities in press history have soared over the last decade with the growing digitization of historical newspapers and magazines. The Russian National Library in St. Petersburg and the Russian Historical Public Library in Moscow have recently made digitally available dozens of newspapers and journals. Among notable efforts outside Russia, EastView holds the largest collection of digitized Russian, East European, and Eurasian newspapers.

To capture the momentum of this new wave in Russian, Eastern European, and Eurasian press history scholarship, Gazeta Workshop offers a digital community for scholars interested in the history of the press. Founded in 2021 by the authors of this post, Gazeta Workshop is an academic forum for scholars in the humanities and social sciences to share research related to the history of the press from the eighteenth century to the present. It offers an interdisciplinary and international community of scholars analyzing the historical press and is currently gathering a repository of links to digitized Russian, East European and Eurasian periodicals.

In 2022, Gazeta Workshop will launch Gazeta Series, a series of lectures on press history. The Inaugural Lecture in the series will be given by Dr. Jeffrey Brooks on April 1, 2022. We invite all readers interested in the history of the press, media, and journalism to join Gazeta Workshop by signing up for its mailing list on its website https://gazetaworkshop.hcommons.org/. Membership is free.