Nessie Kurganova holds an MA in Russian, Eurasian, and East European Studies and Language Teaching Studies from the University of Oregon. A Russian-language teacher and avid birder, she hails from Saratov, Russia.

This post won a Judges’ Choice Prize in the Jordan Center Blog's fifth annual Graduate Student Essay Competition.

In a square Instagram window, a simple interior: a coffee table with evidence of a just-finished meal, a table with kitchenware, paper butterflies gracing the white wall above a flower-printed drape. A middle-aged man in a black tracksuit sits on a made bed, palm pressed to his eyes, mouth strained in a grimace, feet pressed together in self-warming or self-soothing.

An attentive observer may see a bottle of vodka beneath the coffee table, or find that a nearly-finished bottle of coke sports a copycat brand in Cyrillic, or that the table in the background is a makeshift kitchenette and the odd flower-patterned “tapestry” behind it is actually a practical accessory: a splatter screen. These details weave together a sense of comfortable intimacy and hospitality with an almost invasive display of vulnerability: one man cries in his bedroom as another takes his picture with a phone.

This last published work of Russian photographer Dmitry Markov became his most controversial one. What could be a story of masculinity, loneliness, or alcoholism, is pinned by its caption to the Russian war against Ukraine. The text accompanying the image identifies the subject as a Russian man named Andrei who had just returned from Ukraine and was planning to go back.

| dcim.ru's profile picture dcim.ru Edited • 87w С Андреем познакомились, когда гуляли по спальному району Александрова: он вышел забрать у таксиста бутылку водки и столкнулся с нами на узкой заснеженной тропинке у подъезда своей двухэтажки: — Вы заебали тут закладки копать, нет тут ничего… Объяснили, что туристы и напросились в гости. Выяснилось, Андрей вернулся с СВО и собирается обратно. Пьет. Предложил нам гречку с сосисками и чая. Сказал, что возражения не принимаются. Сперва позаботился о нас: разогрел еду и вскипятил воду, подал нехитрый обед, а уже только потом сел, открыл бутылку и налил себе водки. — Не страшно умирать? – спросил я. Долго помолчал и ответил: — Страшно смотреть как умирают… И заплакал. | We met Andrei on a walk around a residential area in Aleksandrov: he stepped outside to get a bottle of vodka from a taxi driver and stumbled upon us on a narrow, snow-covered trail near his two-story apartment building: “Enough with your f***ing digging, there are no drug caches here…” We explained that we were tourists and he ended up inviting us over to his place. It turned out that he had just returned from the SVO [“Special Military Operation,” the Russian state euphemism for the full-scale war against Ukraine—NK] and was about to go back. He drinks. He offered us buckwheat kasha with hot dogs and tea. Said he wouldn’t take no for an answer. First, he took care of us: heated up the food, boiled the water, served up a simple dinner and only then sat down himself, opened a bottle and poured some vodka for himself. “Aren’t you afraid to die?” I asked. He stayed silent for a while, then replied: “I’m afraid to see others dying…” And he started crying. |

The caption takes the visual narrative of the photo in a different emotional and thematic direction, placing it within a specific political and human tragedy. For many viewers, this short bit of text turns the crying man from a victim into a villain; for some, it is a conversation starter, yet for others it is the end of the conversation. Markov’s own artistic discourse ended with this image. Struggling with the backlash and with the dilemma of remaining a faithful artist, activist, and friend in a hostile country that made him who he was, he turned to his life-long vice: drugs. On 15 February 2024, a mere ten days after publishing the post above, Dmitry Markov overdosed in his Pskov flat.

Over the course of his short life and career, Markov rose from writing articles for a student paper articles (in exchange for academic leniency from the college, which he never finished) to publishing photobooks and exhibiting his work in galleries in Moscow, Paris, and New York. Despite these successes, his iPhone camera remained his favorite tool and Instagram his preferred exhibition space—accessible, casual, and self-directed. His raw understanding of life in the streets combined with a deliberate, scrupulous photographic technicality achieved with only a smartphone camera spoke to the global viewer, bypassing the language barrier.

However, his words still mattered. He had begun his career as a journalist, and continued to develop his voice in his Instagram captions, creating complex visual-textual narratives—posts—in an interactive digital medium. Though lauded as a photographer, Markov rarely got credit for his writing, or more importantly, the skillful way he combined the two. This oversight may be because Instagram, a platform most suitable for marrying text and image, is not considered “serious” compared to more “prestigious” formats like books or exhibitions, which tend to separate the “main” medium (photography) for the “auxiliary” one (text).

As for academia, although there is some discourse about multimodality (see Bateman’s 2014 “Text and Image”) and multiliteracy (New London Group 1996), it remains on the sidelines of inquiry. For Markov’s work, one key takeaway from the existing theory is the multiplication of meaning (Bateman): the idea that text and image can merge to create a semiotic unit exceeding the sum of its separate parts. Markov’s last post is a great illustration of this principle, because the photo and the story behind it interact to produce an intricate narrative that couldn’t emerge as clearly from a single modality. While the image invites us to observe the stranger in his vulnerability and keep him company in his solitude, the caption snaps us into the reality of his complicity—while still giving him a voice. Taken together, the post’s photos and caption dare us to confront the disparate layers that make up this moment and face it in its fullness. Without the caption, this photograph would lose its factual truth; without the photograph, it would lose its emotive truth.

Instagram’s built-in flexibility allowed the artist to incorporate multiple elements without compromising readability. With a single swipe, viewers can move between Andei’s photograph to the post’s next shot, which depicts what must be the drafty façade of his house adorned with a ragged, dirty Russian flag. Another component of the post—the location tag—pins the story to a small town in the Vladimir region, a familiar type of environment for Markov. Like many of his peers, he grew up in the province fearing his alcoholic father and scrambling to turn late-Soviet dilapidation and scarcity into a game to play with his street-roaming peers. Markov’s photography conveys a narrative endemic during Soviet collapse, an aesthetic that captured the Western imagination through projects like Molchat Doma, a music band that brought macabre Soviet-esque aesthetics to young Western audiences, primarily through social media. Still, Markov’s work resonates most authentically with those who share the experience of living among the five-story panelki (Soviet apartment blocks) surrounded by decorative animals made of old tires.

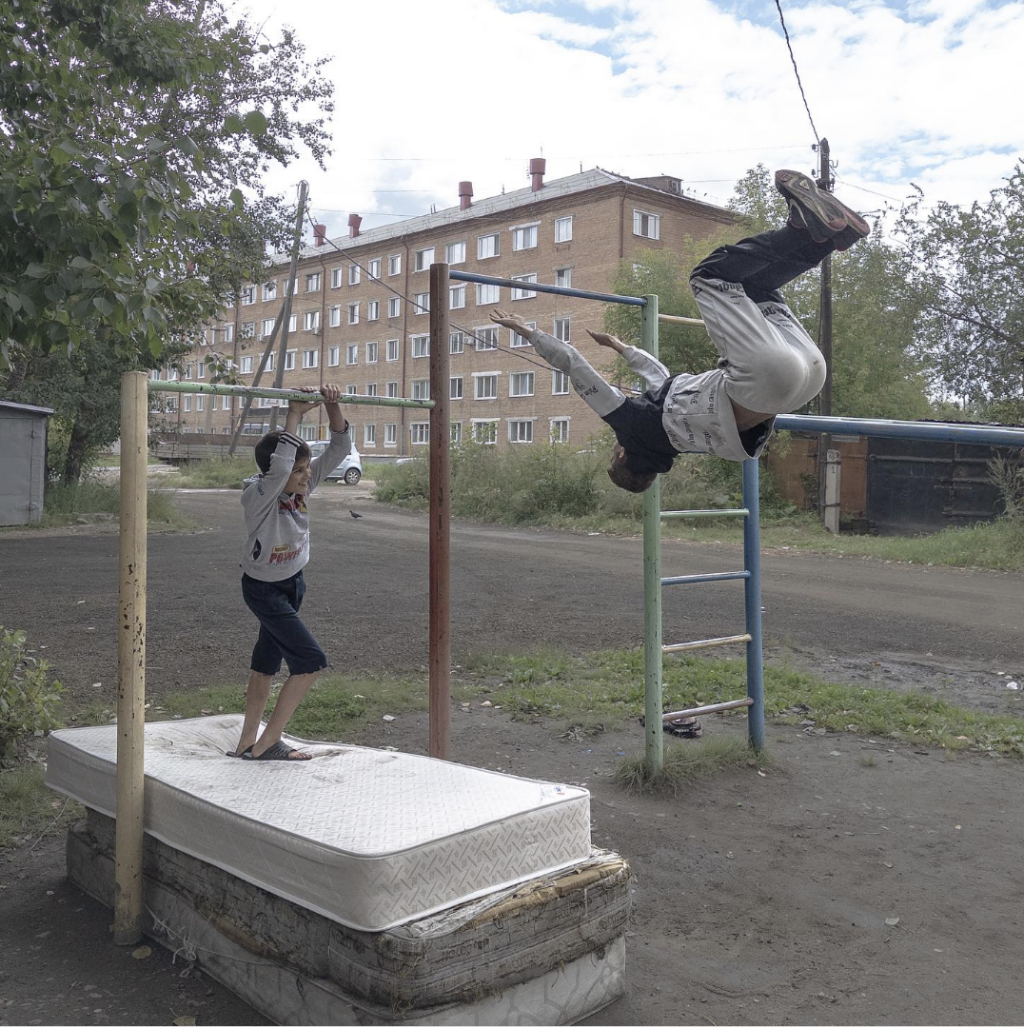

Another, less common kind of experience also colored Markov’s work: his history of addiction, which ended his artistic career and life at the age of 41. Though most of his work can be classified as “street photography,” Markov also reported from insider spaces like pritony (crackhouses) or reby (slang for rehabilitation facilities). When documenting his fellow Russians—carefree children playing in makeshift urban playgrounds, street vendors framed by their listlessly arranged wares, drinkers raising their glasses and lying down on the pavement, churchgoers, drug users, ubiquitous idle babushki, dreamy commuters—Markov was not merely a detached observer, but one with his subjects, sharing a common historical and social reality.

Markov’s lens gravitated to okrainy (outskirts, literally “near edges”) and glubinki (remote places, literally “little depths”): distant residential streets and small towns in provincial Russia like his native Pskov, away from the glamour of manicured boulevards and tourist attractions of Saint-Moscowburg.

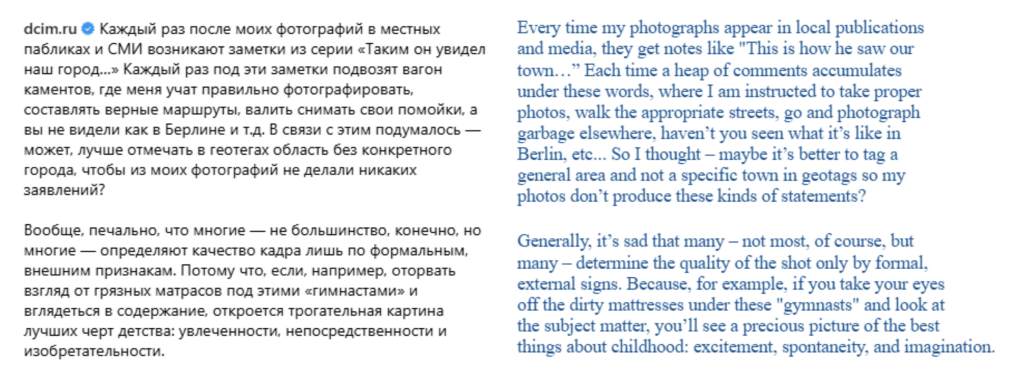

His cumulative portrait of Russia through a thousand faces, playgrounds, and street corners captured Russia “unwashed” (to borrow Mikhail Lermontov’s term), raw and unphotoshopped, inviting scathing criticism for airing the national dirty laundry. Markov’s earnest, unretouched pictures of poverty, ruin, addiction, homelessness, and other unpleasant domains of twenty-first-century Russia led to accusations of an overly negative portrayal of the country in the vein of chernukha. The term, which derives from the Russian chorny (black or dark), appeared during glasnost in the late 1980s and has remained a part of the post-Soviet sensibility as an “unrelenting negativity and pessimism both in the arts and in the mass media” (Eliot Borenstein).

Markov’s subject matter was indeed often dark and heavy, but it is impossible to ignore his optimism and love—sentiments that are self-aware and complex as opposed to blind or contrived. The title of his 2024 memorial exhibition in Moscow, “The Optics of Hope,” testifies to the palpable positivity of Markov’s art. Hope was a critical need in his line of work: besides photography and writing, Markov was a long-time volunteer who worked to help his subjects, especially the homeless, chronic drug users, and children in difficult life circumstances. For an artist-activist, chernukha as an optical frame would entail despair, futility, and repulsion—the opposite of what we see in his life’s work.

This caption captures the signature mood of his work, suspended in a somersault between dirty old mattresses and wide-eyed joy. Markov’s ambivalent love for the unlovable is lucid and sober—not a substance-induced or rosy-goggled myopia, but a carefully sustained and attentive optic that speaks to the public through photos and caption-essays.

And so, as an alternative to chernukha, I propose a more fitting name for the tone of his photography—svetlukha, from the Russian “svetly,” meaning light or bright. This term preserves the same suffix as chernukha to keep the reference to crude, chthonic, dark themes that are, however, brightened by sympathy, love, and hope. A neologism tied to a late-Soviet phenomenon captures Markov’s artistic legacy, which is radically novel yet familiar, rooted in the phenomenology of his subjects and his subjectivity. It also serendipitously ties Markov’s work to the very essence of photography—the process of writing (from Greek graphos) with light (photos).

Markov illuminates a curious world often left unseen, writing zakoulki (nooks and crannies) and their absent-minded pedestrians into a portrait of twenty-first-century Russia that neither absolves nor condemns its subject matter. Instead, his works preserve its unlikely geometries, cruel idiosyncrasies, and fleeting quotidian instants. Just as beauty is in the eye of the beholder, so too is hope. Markov’s work is as much a portrait of Russia as it is a self-portrait: realistic but charged with aspiration for the better, at times unflattering yet never self-dismissing. Quoting from another one of his multimodal posts: “I am a citizen of this present Russia, to the bone. My place is here. I am the two-hundred-ruble bribe. I am this black mold on the benches. I am that ficus plant whose roots grew through the windowsill.”