The Jordan Center stands with all the people of Ukraine, Russia, and the rest of the world who oppose the Russian invasion of Ukraine. See our statement here.

This post features a Judges' Choice entry in the Jordan Center Blog's third annual Graduate Student Essay Competition.

Sergei Motov is a PhD student in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. His research focuses on bureaucrats in Russian and Soviet literature and film.

Dostoevsky's works are replete with careful mentions of ranks and titles that are important for understanding the characters populating his narrative worlds. But there is one rank that the reader encounters with special frequency: that of titular councilor. Titular councilors are the main characters of early Dostoevsky works like Poor Folk and The Double (both published in 1846), as well as key players in his famous Crime and Punishment (1866) and The Brothers Karamazov (1880). The recurrence of this rank throughout Dostoevsky’s most significant works begs the question, why are they all titular councilors?

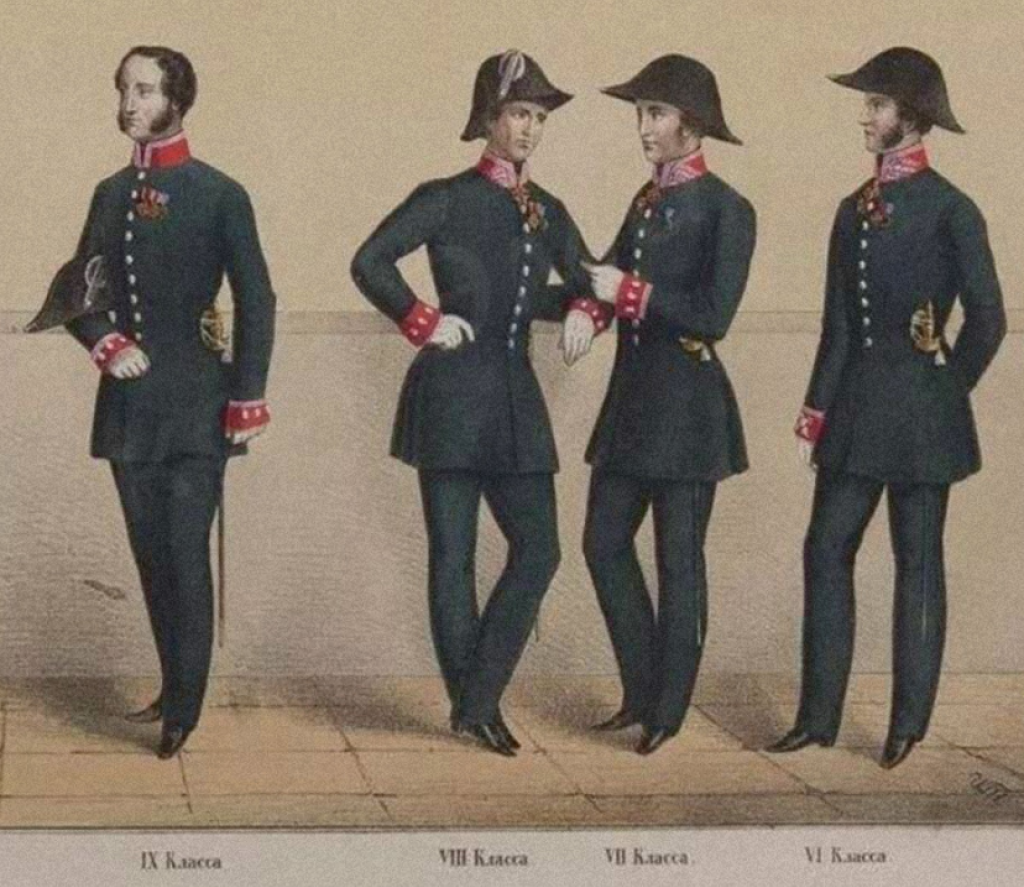

To find an answer, we must look at the social role of the titular councilor in the nineteenth century. The civil service hierarchy known as the Table of Ranks, imperial Russian law, and statistical and archival data all indicate the uniqueness of the titular councilor in the first half of the nineteenth century. Of the 14 ranks included in the Table of Ranks, the titular councilor at rank 9 is the boundary between the higher ranks that conferred hereditary nobility (1-8), and the lower ranks (10-14), which held limited prestige.

A titular councilor only needed to take one more step to get to rank 8, which guaranteed hereditary nobility. The status of a hereditary noble meant belonging to the elite of the society and granted many privileges, most prominently owning serfs or land, that others (including those who belonged to much less valued personal nobility) could not enjoy. However, this step to hereditary nobility was especially difficult to make. In fact, the rank of titular councilor turned out to be a real trap for most of its bearers. Precisely for that reason, writer Nikolai Gogol, who had a strong influence on the work of the young Dostoevsky, called such officials “eternal titular councilors.”

The beginning of Dostoevsky’s career as a writer coincided with a period of social, financial, and bureaucratic reforms during the 1840s. The 1845 edition of the Table of Ranks significantly raised the threshold for hereditary nobility. Now only ranks of 1-5 guaranteed hereditary nobility, while the ranks of 6-9 conferred only personal nobility and the ranks of 10-14 were deprived of it altogether. These changes fundamentally altered the significance of the rank of titular councilor. Before 1845, it was seen as only one step away from hereditary nobility, but after the reforms, it became a “consolation prize” that guaranteed personal nobility for the lower ranks. Although this change made it a desirable rank in itself, holders’ long-term prospects in the civil service had now dimmed.

This change soon found reflection in literary depictions of the rank. While writing his second novel, The Double, which coincided with the bureaucratic reforms of 1845, Dostoevsky wrote in his notebooks that the novel’s protagonist, titular councilor Golyadkin, was “ready to resign.” In the novel's first edition, from 1846, Golyadkin is considering the possibility of resigning from service. However, in the second, 1866 edition, this passage is absent: Golyadkin never even considers leaving his post. Despite the fact that this plot twist did not make it into the version of the novel that is most studied and translated, the image of the former titular councilor became a hallmark of Dostoevsky’s work.

A key feature of Dostoevsky's writing, according to literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin, is the concept of the threshold. Dostoevsky’s key characters are in a state of constant uncertainty, which coincides with their presence and action in liminal spaces: on the physical threshold, a landing, a crossroads, a bridge, or a tavern linked to a character’s social imbalance or psychological ambivalence. In the case of the former titular councilor, we are dealing with double ambivalence. First, the very name of the rank of titular councilor indicates a gap between the signified and the signifier—it belongs to the respected class of councilors only formally, without according the corresponding privileges. This fact proceeds from the very meaning of the word “titular,” that is, nominal or purely formal, as well as its position closer to the bottom of the Table of Ranks.

Second, the status of a former titular councilor only exacerbates this gap and makes us wonder if this person is even an official at all. A characteristic image of the former titular councilor is Semyon Marmeladov from Crime and Punishment. It is difficult to recognize this bitter drunkard as a relatively high-ranking civil servant, although according to the Table of Ranks, he is a personal nobleman! A liminal figure, he vacillates between reason and oblivion, service and idleness, and, ultimately, life and death. The image of “eternally unstable” Marmeladov was Dostoevsky's reworking of his own first representation of the “eternal titular councilor”— Makar Devushkin from Poor Folk. Together, these characters reflected important bureaucratic and social changes in the Russian Empire in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Apparently on the opposite end of the spectrum from Devushkin is former titular councilor Fyodor Karamazov. If Devushkin is a classic meek eternal titular councilor, conscientiously serving the state despite extreme poverty, then Fyodor Karamazov is an old debauchee who abandoned his service long ago, relying on the power of money to achieve his own pleasures. In a way, Karamazov is a bitter parody of the titular councilors of old and their antithesis—the logical endpoint of a characterological evolution that started with Devushkin and continued through Marmeladov.

So why did the titular councilor become so attractive to Dostoevsky? On the one hand, this is a liminal position in the Table of Ranks. At first, it separated the high hereditary nobility from the much less valuable personal nobility and later, personal nobility from non-nobility. On the other hand, its very name is paradoxical, implying belonging to a high class of councilors in form, but not in substance. Either way, we have an unstable, borderline rank ideally suited for Dostoevsky’s unstable and liminal characters.

Ultimately, Dostoevsky’s depictions of former titular councilors respond to the literary type of the “eternal titular councilor” proposed by his predecessor Nikolai Gogol. Both images reflect the historical context and the ambivalent position of middle-tier bureaucrats who have become a literary type. The “eternal titular councilor” of the first half of the nineteenth century turned out to be the embodiment of bureaucratic failure, forever stuck in a trap rank. In turn, the former titular councilor found in Dostoevsky’s late works reflects the depreciation of the bureaucratic career in Russian society in the century’s second half, epitomizing a nobility gone to rot.