Peter Rutland is a professor of government at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut.

This post originally appeared on Transitions Online.

Navalny’s battle of wills with Putin is not likely to end well – at least in the short term.

Alexei Navalny’s return to Moscow on 17 January is a pivotal moment in Russian history. His decision to go home after five months recuperating in Berlin was an act of extraordinary bravery, one with few parallels in modern times.

He knew that he faced almost certain imprisonment, and possibly death. The only uncertainty is how long he will be held in prison – one month, one year, 10 years?

So why did Navalny return?

Russia politics now seems reduced to a battle of wills between Vladimir Putin and Alexei Navalny. It is a grossly unequal combat, since Putin has all the resources of the state at his disposal, from a compliant legal system to military-grade chemical weapons.

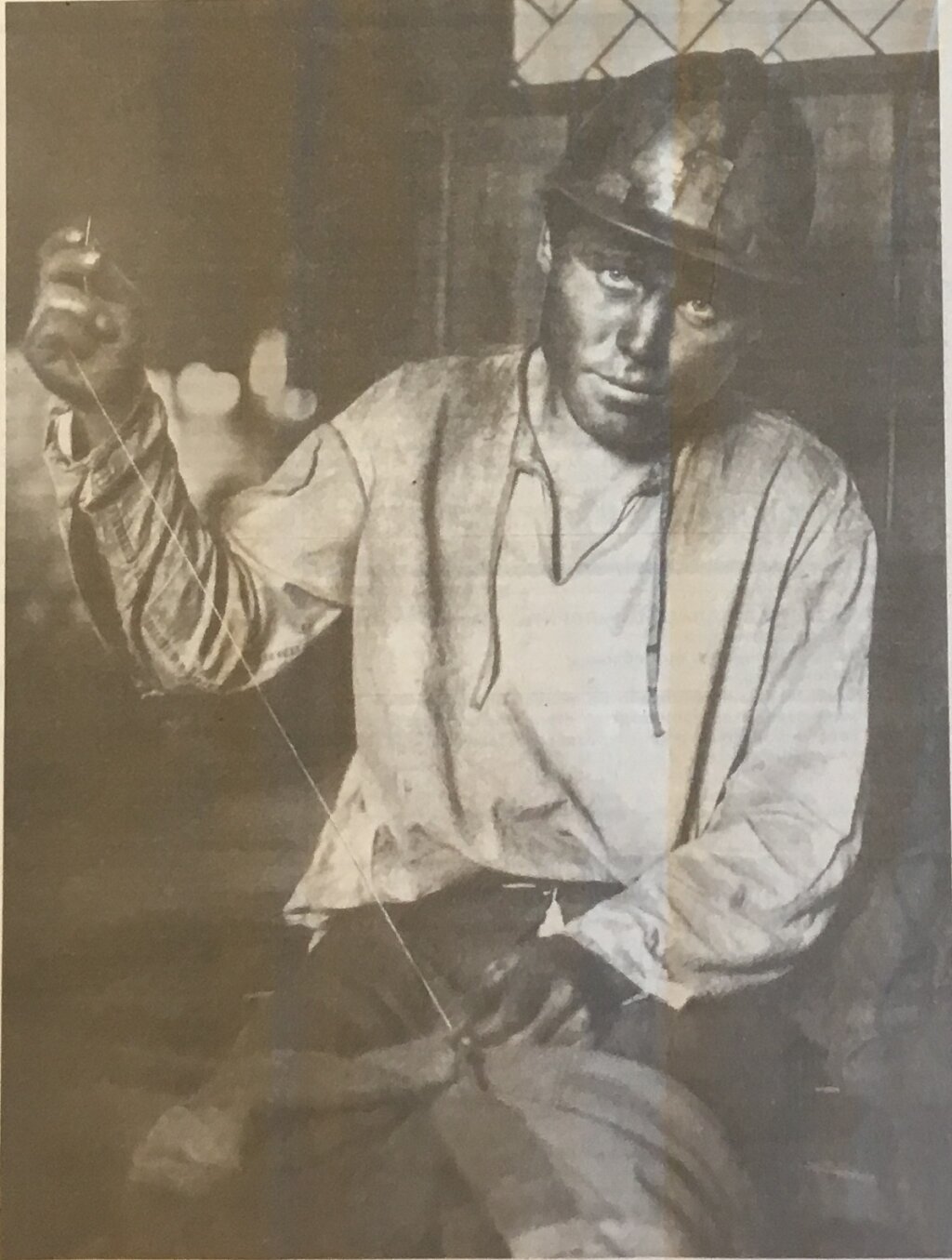

Navalny is David to Putin’s Goliath. His main weapon is not a slingshot, but weekly YouTube videos exposing the corruption of Russia’s ruling elite. His latest, released on 19 January, documents the financing of Putin’s $1.5 billion “palace” on the shores of the Black Sea. (It introduced the term “mud room” to the Russian language.) Within a week it had attracted 86 million views.

Putin has long curated his own image as a muscular, macho leader, the only man who can save Russia. State institutions have been hollowed out, and the regime’s legitimacy rests on Putin’s personality cult.

Putin easily brushed aside the challenge to his masculinity from the women of Pussy Riot in 2012. But now he has met his nemesis: a man who has proved his courage by facing down repeated physical assaults, and who is manifestly willing to die for his cause. Navalny came close to death when he was poisoned with Novichok in August. He spent 18 days in a coma, and almost miraculously returned to life.

So Navalny’s challenge to Putin is not just political – it is personal. Putin has tried to avoid this, refusing to utter Navalny’s name, and referring to him instead as “the Berlin patient” or “this gentleman.”

In a 2017 interview, YouTuber Yurii Dud asked Navalny which political figure he most admired. Without hesitation, he replied “Jesus Christ,” citing his role in bringing about a revolution in social values. Navalny himself is not a religious person – but he does see himself as the savior of Russia, and thus Putin’s rival.

When Dud pressed him to name a more conventional politician, “one who wears a suit,” Navalny chose Nelson Mandela, who surfaced from 27 years in prison with the moral authority to lead his nation into a new era. Navalny himself has been jailed a dozen times for short periods after being arrested at protests. In 2014 he was given a suspended sentence of three years in a patently false fraud case: that is the excuse for his current incarceration. His family’s bank accounts have also been blocked.

Some have compared Navalny to the physicist Andrei Sakharov, exiled to a provincial city for criticizing the Soviet Union’s human rights record. Russia has a long tradition of intellectuals speaking truth to power, though it usually ends badly for the intellectual.

Observers disagree about Navalny’s political values. Is he a liberal? Is he a nationalist? But there is really no ambiguity in his political agenda. His goal is revolutionary change. He does not believe that it is possible to hold Russia’s leaders accountable within the existing political system. The investigative journalism, the protests, and the election campaigning are just a means to the end of regime change.

This sounds like a Quixotic, if not megalomaniac, mission. But it is not the first time in Russian history that a revolutionary returned from abroad to topple the ancien regime. Navalny is often described as a modern-day Lenin – and it is not meant as a compliment. Many Russians see 1917 as a disaster for the country, with Lenin sent by Germany to sow chaos. Hence it is easy for the Kremlin to portray Navalny as a foreign agent. This is the line pushed by the siloviki (security officials) in the Kremlin, who have been given a free hand to crack down on the opposition over the past year.

In the West, Navalny is seen as a symbol of Putin’s disrespect for human rights. Navalny welcomes Western support – he encourages the sanctioning of Russian officials. But his most important audience is the Russian people.

Despite his wide audience on social media, polls show minimal public support for Navalny as a potential replacement for Putin. A September Levada Center poll found 20 percent approved of his political activities – with the strongest backing among the young.

Outrage at Navalny’s arrest led to protests in more than 70 Russian cities on 23 January. Over 3,000 people were arrested, and several of Navalny’s key aides were detained in the days leading up to the unsanctioned protests.

It looks unlikely that Navalny will succeed in his quest to topple Putin in the near future. He will probably remain a prisoner, a modern-day equivalent of Alexandre Dumas’ “Man in the Iron Mask.”

But his very existence serves as a moral rebuke: a symbol of the Russia that might yet be.