Luka Nakhutsrishvili teaches critical theory at Ilia State University Tbilisi. In Fall 2021, he is a Fulbright Visiting Scholar at NYU's Department of Anthropology.

When you walk down Rustaveli Avenue, the main street of Tbilisi, the Georgian capital, and reach the corner lying between the National Gallery, the Tbilisi Marriott Hotel, and the uppermost edge of the 9th of April Park, you might notice, in the shade of the trees, a life-sized bust of the writer Egnate Ingorokva (1859-1894), whose pen name was Ninoshvili (Fig 1.).

(Above) Corner of Chanturia street between Tbilisi Marriot Hotel and the National Gallery, with Ninoshvili’s bust barely visible in the yellow circle. Source: Photo by the author. (Below left) Bust of Ninoshvili by Iakob Nikoladze. Source: http://georgianart.ge. (Below left) Map of Rustaveli avenue: 1. Tbilisi Hotel Marriott, 2. Bust of Ninoshvili, 3. National Gallery, 4. 9th of April Garden, 5. First Public School, 6. Statue of Ilia Chavchavadze and Akaki Tsereteli, 7. Parliament, 8. Freedom Square. Source: Google Maps customized by the author

Ninoshvili was one of the founders of the Georgian Marxist movement. Only his untimely death from tuberculosis at age twenty-five cut short his literary and organizational activities. Claimed by both the Menshevik and the Bolshevik factions into which the Georgian revolutionary movement split after 1903, he ended up being celebrated in Soviet times as the peasant-proletarian writer who ran ahead of the still-emerging Georgian working class. In the wake of the 2003 Rose Revolution, a series of educational reforms ejected him from school curricula as part of a nationwide drive to aggressively neoliberalize all spheres of life, discarding any kind of social criticism as “Soviet” and therefore outdated.

Little wonder, then, that there is something suspiciously inconspicuous about how Ninoshvili’s bust fits into its surroundings, remaining unremarkable in an otherwise hyper-central spot on the main street in the capital. This inconspicuousness is the result of multiple re-layerings of his memory, which have gone hand in hand with fundamental shifts in politics and literature through the hundred years since the bust's initial unveiling. The system of coordinates within which Ninoshvili’s figure held a specific function has become distorted to the point of making the bust's location incongruous with its surroundings.

As a first step toward recovering these coordinates, I propose a brief montage of images pertaining to one particular bust, leaving it to a future, more in-depth inquiry to ask several interrelated questions: What did Ninoshvili actually write? How did he come to be hailed as a beacon for the proletariat while, in reality, writing exclusively about peasants, and why does this distinction make such a huge difference in the Soviet context? Answering these questions would amount to a somewhat indirect retelling of the modern history of Georgia, where, as in any other place shaped first by tsarist, and then by Soviet rule, literature and politics were inextricably intertwined.

Ninoshvili became famous for writing about his home region of Guria in western Georgia and the desolate fate of its peasantry, whom the Great Reforms had liberated from serfdom — only to catapult them into a rapidly transforming economic, administrative, legal, and cultural milieu located in a peripheral district of a peripheral region of late imperial Russia. Marrying social criticism and ethnographic accuracy in the spirit of Russian militant realism, the darkness and graphic incisiveness of this fiction, unparalleled in all of Georgian literature, so captivated the cultural imagination that it inspired the first Georgian feature film in 1916, as well as the first Georgian opera in 1918.

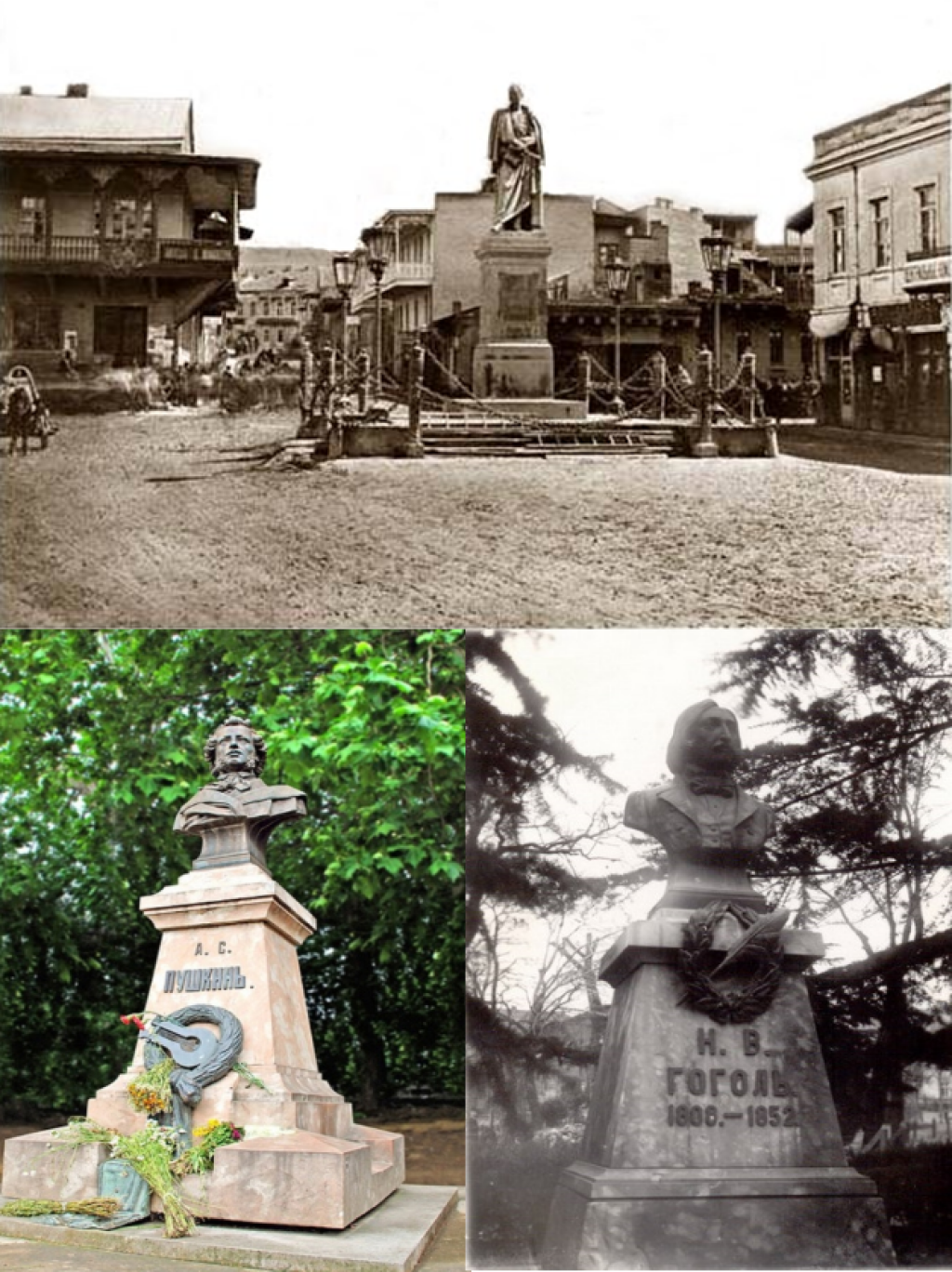

From a post-Soviet perspective, however, it remains puzzling why Ninoshvili was the first Georgian figure to be considered an appropriate subject for public sculpture. Due to its roots in Orthodox Christianity, which did not encourage three-dimensional sculpture, Georgia had had no sculptural tradition before the Russian imperial project set out to “Europeanize” the urban order of a formerly Persian-influenced city. So, when the first Georgian professional sculptor, Iakob Nikoladze (1876-1951), began work on Ninoshvili’s bust in 1908, there existed only a handful of public monuments: one to the acclaimed Viceroy of Russian Transcaucasia Mikhail Vorontsov (erected in 1866) and busts of Pushkin (1892) and Gogol (1903) (Fig. 2).

(Above) Monument to Mikhail Vorontsov photographed by Dmitri Yermakov. (Below left and right) Busts of Pushkin and Gogol by Felix Khodorovich. Source: https://burusi.wordpress.com. Vorontsov’s statue was removed by the Bolsheviks in 1922. Gogol was stolen in 1990. No one seems to have dared touch Pushkin.

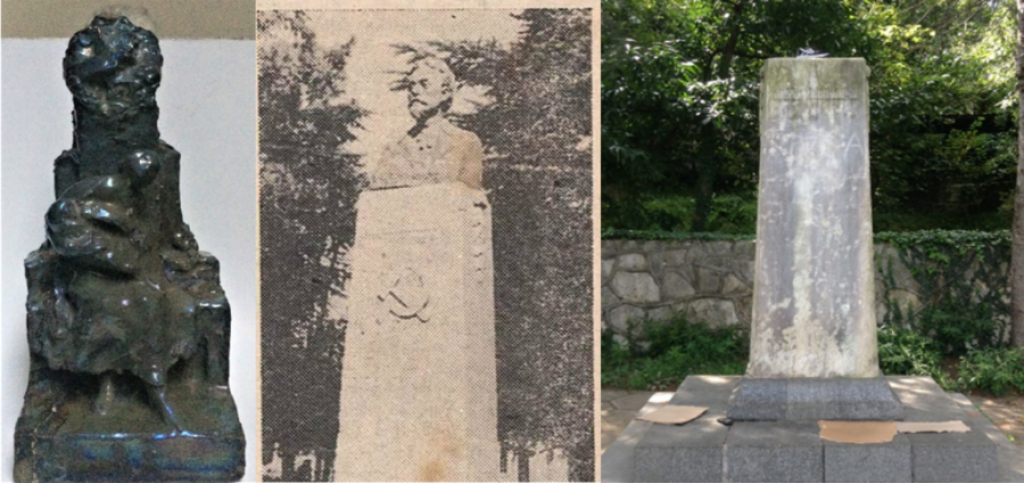

As the sculptor worked on it, Ninoshvili’s bust underwent a radical evolution. In 1909, a Georgian newspaper reported that they had received Nikoladze’s project for the sculpture, with a pensive Ninoshvili lying ill in his bed, leaning on a pillow with pen and paper in hand and drapery covering his feet. While it was impossible to trace the origins of this image, a maquette of another, equally complex version has survived, which deviates from the final — and rather conventional — result. The maquette shows a woman sitting in front of the pedestal with a baby in her arms, as if seeking shelter in Ninoshvili’s shadow and looking anxiously behind her. Curiously, in this maquette, Ninoshvili’s head is cut off — a fate that befell not only some of his literary characters, but also his own memorial, which was first erected in in his home region during late-Soviet times before getting stolen in the 1990s (Fig 3.).

(Left) Maquette of Ninoshvili sculpture by Nikoladze. Source: Photo of the author, courtesy of the Nikoladze House Museum in Tbilisi. (Middle) Ninoshvili’s bust, modeled after Nikoladze’s work, in Soviet Ozurgeti, administrative center of Guria. Source: http://aboutguria.blogspot.com. (Right) The same pedestal today without a bust and the hammer-and-sickle symbol inelegantly scrapped off. Source: https://diariesofjournalist.wordpress.com

It was not until 1923, that is, two years after the Bolsheviks had sovietized the Menshevik-led Georgian Democratic Republic (1918-1921), that Ninoshvili’s bust was unveiled to the sound of the “Internationale," the speeches of Bolshevik leaders, and the poems of worker-poets. The spot to which the bust had been assigned was highly significant. It was part of the Bolshevik re-appropriation of the Alexander Garden as the first European-style green space developed under tsarist rule in 1859, before being re-baptized as the Garden of the Communards and ultimately becoming the 9th of April Park. Just behind the bust's position, the Bolsheviks had several months earlier buried three commanders of the Gurian Red Army as “victims of Menshevik banditry.” Thus, Ninoshvili’s bust came to stand at the entrance of a future Bolshevik pantheon, with many more martyrs of the revolutionary struggle buried beneath, or represented within, the garden's upper area.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, all traces of this pantheon were gradually erased. Gravestones were either relocated or lost, leaving Ninoshvili’s bust bereft of its spatial-symbolic context. However, the dismantling of this context did not start with the demise of the Soviet order. Already in 1958, a huge monument was erected on the square in front of the First Public School (Fig. 4). This monument depicted Ilia Chavchavadze (1837-1907) and Akaki Tsereteli (1840-1915), two writers of noble origin whom Ninoshvili and his fellow radicals considered the embodiment of nostalgic aristocratic nationalism.

Statue of Chavchavadze and Tsereteli by Valentin Topuridze. Source: https://mapio.net

The creator of this double statue was Valentin Topuridze (1908-1980), who, two years prior, had seen his monument to Lenin placed on Tbilisi's main square at the end of Rustaveli Avenue (Fig. 5).

(Left) Statue of Lenin by Topuridze. Source: www.pinterest.com. The statue stood on Lenin Square, which today is called Freedom Square, featuring instead an oversized golden monument of St. George (right) by the ubiquitous Zurab Tsereteli. Source: https://commersant.ge

The large scale of the Chavchavadze-Tsereteli statue and its propitious position in a larger space forcibly shifted the spatial coordinates of Ninoshvili’s small memorial (Fig. 6).

Caption: (Left) Looking towards Ninoshvili’s unremarkable bust from the back of the double statue. (Right) Looking towards the always-remarkable double statue from the back of Ninoshvili’s bust. Source: Photos by the author.

As before, this spatial shift was preceded by a significant ideological change. Until the 1930s, many a radical writer would dismiss figures like Chavchavadze and Tsereteli as former class enemies of a now-victorious proletariat. However, with the onset of Stalinist national-cultural policies, a more “evened-out” model of Georgian literary history emerged. In this scheme, Ninoshvili, though still acknowledged as the father of a certain “tradition of the oppressed,” was reframed as the spiritual descendant of such “fathers of the nation” as Chavchavadze and Tsereteli. It was this Stalinist nationalism that set the stage for the anti-Soviet nationalist literary history of post-Soviet times, which shook off its socialist aspects in favor of the purely national — leading to the “social writer” Ninoshvili being thrown overboard altogether.

Even as the Georgian Civil War raged on Rustaveli Avenue in 1991-1992, Ninoshvili's bust remained unscathed. The opposition's bullets and bombs flew right over Ninoshvili’s head toward the Parliament, where the first president of the newly-independent Georgia, Zviad Gamsakhurdia, had found shelter in a bunker (Fig. 7).

(Left) The corner of the Hotel Tbilisi as seen from the angle of Ninoshvili’s bust during the Civil War. (Right) Side shot of the monument to Chavchavadze and Tsereteli with the bombed First Public School and Parliament in the background. Photos by Shakh Aivazov. Source: National Parliamentary Library of Georgia. None of the pictures that have captured the devastation of the area seem to have bothered to include Ninoshvili’s bust, whereas Chavchavadze and Tsereteli are featured in every shot of the bombed Public School, mutually enhancing a sensation of tragic monumentality.

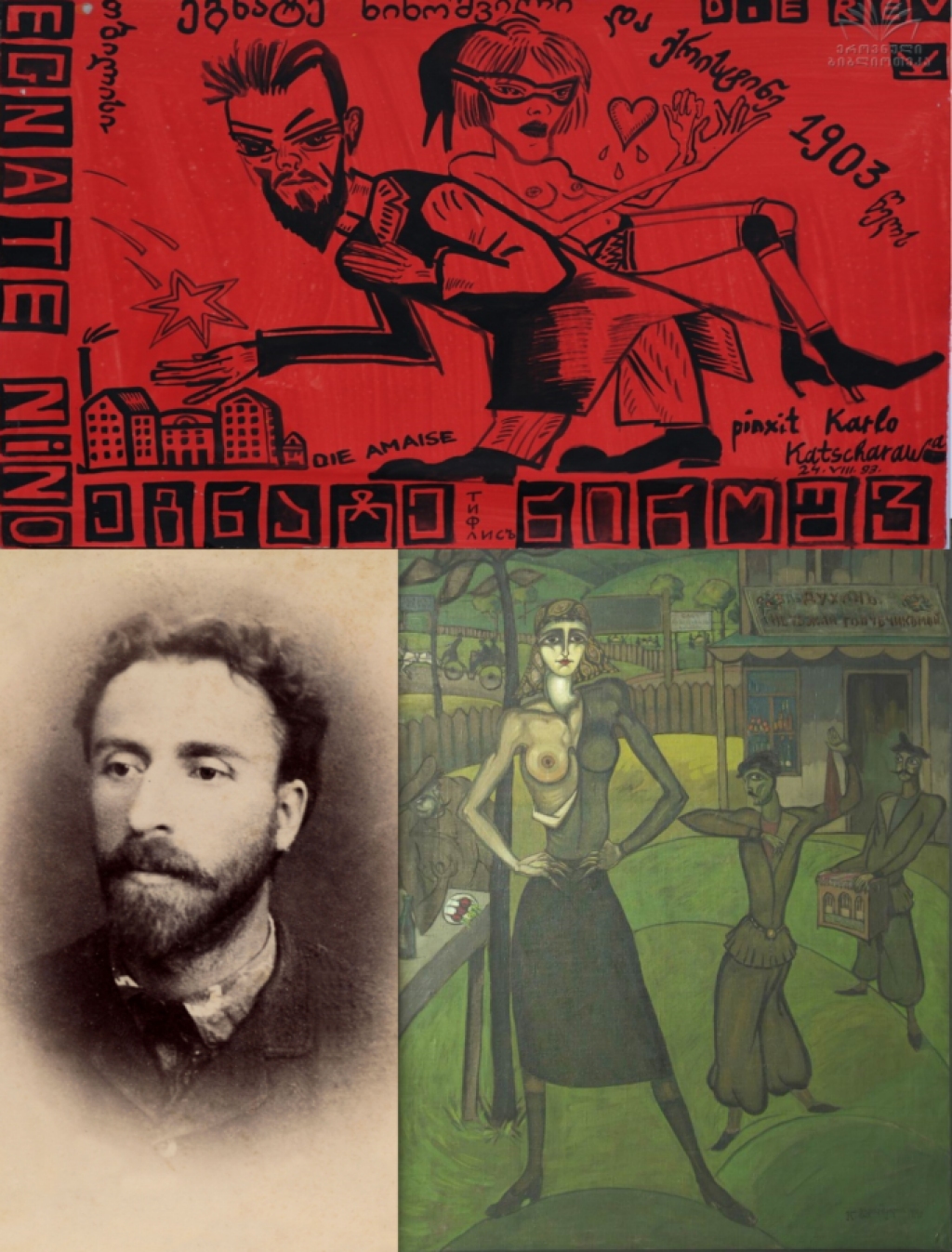

Ninoshvili’s bust got off relatively light, pierced by a single bullet hole. Meanwhile, in a reference to the same unique photograph of Ninoshvili that had served Nikoladze as the model for sculpting the bearded male “classic,” the painter and poet Karlo Kacharava represented him in somewhat distorted form. We see him carrying on his back a no less distorted version of the painter Lado Gudiashvili’s 1919 rendition of his most famous female character, Kristine, the Gurian peasant girl who turns to prostitution (Fig. 8).

(Above) Ninoshvili and Kristine by Karlo Kacharava. (Below left) Photo-portrait of Ninoshvili by Alexandre Roinashvili (c. 1888). (Below right) Kristine by Lado Gudiashvili. Source: National Parliamentary Library of Georgia

Ninoshvili's image was thus called upon to represent a damaged existence in the wake of post-Soviet “shock therapy.” One of Kacharava’s most famous poems from 1992, at the peak of Georgia’s political and humanitarian crisis, shows “Egnate Ninoshvili’s specter combatting the night of those queuing for bread” and trying to “lure the tongue-bereft proletariat out of hiding.” In the end, the specter is too weak to actually help. And yet, there he is — as challenging as the somewhat low-key haunting of a specter can get.