Geoff Cebula is a translator and author of the contingent labor thriller Adjunct.

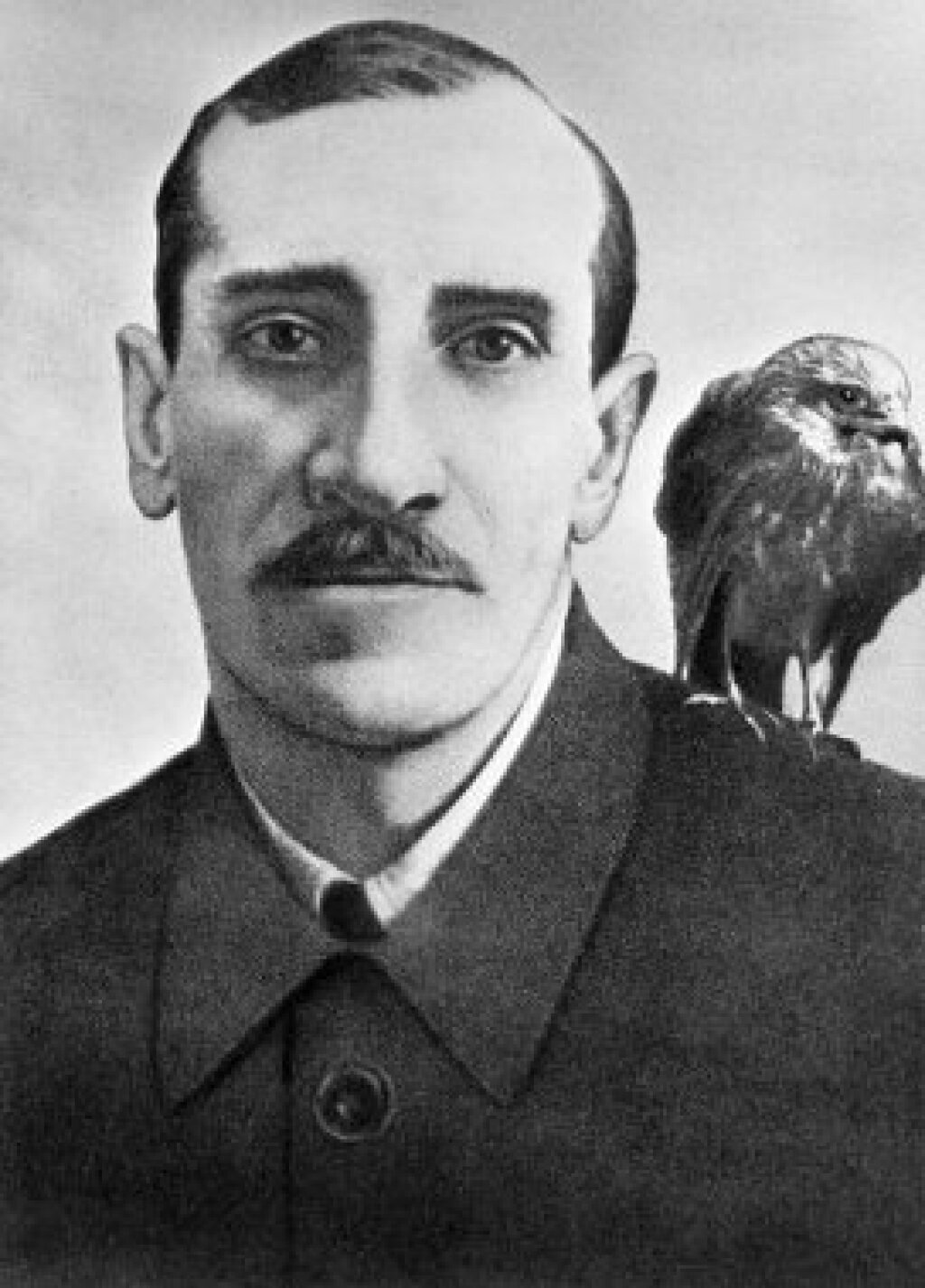

Alexander Grin, renowned author of Scarlet Sails and other fantasies, had a beloved pet hawk named Gul’-Gul’. Presumably, he never told Gul’-Gul’ this story.

This city used to be packed with people, each good for at least one extraordinarily strange story, if not several. Some of these people died long ago, yet when I pass through the cemetery my nose can tell the precise graves in which their former bodies rest after living through a trying stretch of bizarre experiences. I recall their names, how they looked, the way they used to cough or extract their cigarettes.

To this day, an old courier stands at the corner of Miscue-Miscreance and Herbivory, having destroyed his youth and the beautiful home life he shared with his beloved wife by taking it upon himself one day to procure a caged bird without pay. This task was given to him by a beautiful young woman dressed elegantly and aromatically. Though the courier was himself a heartbreaker, married only recently to a sweet but restless blonde, this young woman was of exceptional beauty. He felt stricken in the heart. This fiery-eyed beauty didn’t happen to have any money on hand. “Listen here,” said the courier. “I’m just an ordinary guy, miss, but allow me do you this service for free.”

“Thank you,” she answered simply, with a smile—and her smile imbued the courier’s flustered soul with an incendiary gleam of joyful excitement.

The young woman disappeared into the crowd. Meanwhile, the courier set off for her address carrying a cage in which a scared little canary rattled around. He arrived at a tall gray building on a distant, foggy street shrouded in factory smoke. The street was dirty, but the house was magnificent. A stairway decked with rugs and flowers led the courier to apartment 202. He rang, and the door was opened by the young beauty herself.

The courier handed her the cage, mumbled a few words, and—turning red from his sudden, agonizing infatuation—wanted to leave, but the young woman laughed and said: “Don’t worry, my dear. Let this be a little adventure.” She took his large hand in her own small, petal-like hand and led him through a suite of gloomy, high-ceilinged chambers.

On account of the lowered curtains, a sullen, desolate twilight reigned throughout. The paintings and furniture were covered. Somewhere, mice were secretly scratching. The woman led the courier to a remote room and locked the door. His heart pounded with vague agitation. It was bright and comfortable in here: there was a fire in the fireplace, sculpted porcelain smiled, lilies and camellias shone in red-and-white patterns on bluish pots, and amidst the satin furniture, finery of all kinds, and the subtle aroma of a charming feminine nest, the courier’s will grew weak. Back home it was dinner time and his wife worried about him. But he hardly remembered. His attention was soon drawn to a row of empty cages hanging on the wall opposite the fireplace.

“I buy them and set them free,” the beauty said. Losing no time, she behaved in a captivatingly provocative way, and the courier was under her control. He awoke late in the morning from a deep, heavy sleep. A breakfast with coffee had somehow been served and now let off steam on a little white table. The lovers replenished their strength, and the young woman said capriciously:

“Here’s the address of a pet store. You will go there three times a day and buy me one thrush, one chaffinch, and one siskin. Leave for the first set right away.”

Mechanically obeying, he left and soon found the store. Here, inside this confined, poorly lit shop, a fidgety, trembling old man sat next to an iron stove. He had a dull gaze and a high, derisive voice. The idiotic eyes of parrots gleamed from the cages on the wall. Their unnatural bantering mixed with the ringing whistle of the titmice, the canaries’ overflowing trill, the cooing of the doves, and the other sounds emitted by the countless feathered beings hiding in the depths of their cages. Behind the counter, one could see bins for drying out hempseed, various mixtures of grains, pistachios, soybeans, and the other dishes of an avian restaurant. The smell of feathers and ammonia was in the air.

After buying the assigned birds, the courier wrapped the cages in newspaper and returned to his sweetheart.

Along the way, he remembered that he didn’t know anything about her past or who she was, not even her name, but once he rang her doorbell, he forgot all about it.

The young woman met his purchase with an expression of unbridled enthusiasm, and her pink face, with its fiery eyes, blushed with an exceptionally lively, oppressive beauty. While the courier hung the cage alongside the others at her behest, the woman chatted tenderly with the birdies, as if she were the personification of love for nature’s delicate little children.

Glancing, by chance, at the canary cage from yesterday, the courier noticed that the bird wasn’t there anymore. When he asked about this, he was told that the canary was released at dawn.

“And of course, it was oh so happy,” the woman exclaimed.

The courier kissed her. And so, one day, then another, then another passed in caresses, food, passion, and sweet little nothings, and every day the courier went out to buy some songbirds and awake to find the new cages empty. Every night he slept deeply and soundly, without seeing his alluring lover make a sacrifice to freedom at dawn, releasing the tiny flying creatures with her tender hand.

On the fifth night, a porcelain plate happened to fall from above the bed and hit the courier hard on the knee. He leapt up and looked around. He was alone: his sweetheart had disappeared. He called for her, to no effect. Rising, the young man went into the neighboring room, but no one was there either. He passed through several empty rooms before finally pushing open a door half-hidden behind drapes to see his sweetheart sitting by the fireplace with a titmouse and its cage in her hands. With a mad laugh, she threw the bird into the pale heat of the piled coals. A convulsively squealing tangle of smoke thrashed about, kicking up a cloud of cinders in the red grate. Three times or so, something pitiful and formless flew up, and—falling, twitching—it started quietly to sizzle. The woman grinned widely, and a horrific happiness shone on her deathly pallid face.

“Vile witch!” shouted the courier, growing cold. His hair stood up straight, and forgetting himself, he lunged at the woman, fists swinging.

Half-dressed, she leapt up, dropped the empty cage, and disappeared through the opposite door. Shaking, the courier went back, hurriedly got dressed, and ran outside. It was early in the morning. Stunned by what he had seen, the young man decided to go warn the owner of the pet store, figuring that the latter would stop selling to the woman. He intended to tell him her address and how to recognize her. To his surprise, however, the courier couldn’t find the store he knew so well. It was the right spot on the right street: the church was across the way and a row of houses in a distinctive configuration filled this small block at the city’s edge—they were the same houses that were there yesterday—but it was as if the pet store, with that peacock and deer on its sign, didn’t exist. Taken aback, the courier passed back and forth several times, from one corner to another, looking at every stone of every house. But the store had vanished. In the spot where it had been, or might have been, there was a fruit stand. The courier finally started questioning the local residents, but they all answered in surprise that there had never been any bird store on the block. Then a strange suspicion took hold of the courier. Beside himself, he hurried to the house where the young woman lived, summoned the doorman, and asked him who was renting apartment 202. “It’s empty,” said the doorman. “You see, it’s been a while since we’ve had any repairs done in the building. The owner went broke, and now the house is in shambles. Our boiler’s broken, and it’s cold. The owner doesn’t even come here. It’s been empty six years now. Besides, we only have eight apartments to rent.”

Reeling, the courier stepped outside and, regaining some control, went home. He was in a great hurry. He was tormented by excruciating remorse. With pity and longing, he thought of his wife, who was probably sick from worry and suspense, and remembered his bright, warm dwelling with all its cherished details: the poker alongside the calico-curtained stove, the bright old samovar, the geranium in the window, the cat with its sliced ear—he saw all this in flawless definition, as if he were already sitting down to breakfast at home. But when he arrived, he learned that his absence had lasted three years: other people were renting his apartment, and his wife had died not long ago in the municipal hospital.

This courier always bows to me, since I’m happy to toss him some change for odds and ends. There is something unspoken in his eyes. He’s aged badly and loves to spend his evenings sitting in the tearoom. He sits there for hours, looking down, motionless, ruminating over a glass that has grown cold, while a cigarette goes out in his drooping hand.