Above: H&M imitates a Gosha Rubchinsky sock design, 2017.

Martina Urbinati is a contributor to EastJournal. She holds an MA in social sciences from the University of Bologna.

On December 25, 1991, Mikhail Gorbachev uttered his final words as the last leader of the Soviet Union. What came next was a decade of "catching up" with the West in which the “sick patients” both in Eastern Europe and Western Asia were "treated" with neoliberal shock therapy and globalization injections in high doses. However, the artificial replication of Western models left unanswered the question of how to define the culture that emerged following the collapse of the USSR.

The term "post-Soviet" has become a broad and cumbersome label for a diverse cultural production which, though specific in temporality, has remained vague in essence. Does it still make sense, then, to speak of a "post-Soviet" cultural space? Despite countless attempts to find new terminology to replace the politicized term "post-Soviet," there is as yet no consensus. The (de)construction of cultural imaginaries after 1991 continues apace.

Whereas the West experienced what is often called the “cultural turn” in social theory starting in the 1970s, the social sciences in Soviet Russia were subordinated to official state ideology. With the advent of perestroika, it became clear that Russian social science was largely unprepared to formulate a new interpretation of local changes in practice and representation. In the aesthetic realm, the process of emancipation from decades of Socialist Realism has left an indelible mark on contemporary Russian culture. The West, for its part, tends to perceive "post-Soviet" culture as inexorably linked to Russia's totalitarian past, rather than as a series of truly new or self-sufficient aesthetic choices.

In his 2011 essay "Post-Soviet: Otherness and the Aesthetic of Disappearance," Haris Giannouras invited the reader to consider if the archaic and oversaturated Western canon could possibly be moved from its colonialist desire to "discover" an exoticized communist East. The popularity of dystopian narratives like Anthony Burgess' Clockwork Orange (1962) or Stanislaw Lem's Futurological Congress (1971), combined with Cold War-era propaganda, have produced a disregard for cultural productions rooted in failed utopia — at least until recently, when Western media began paying closer attention to Eastern European culture.

A shift from "post" to "post-post" not only coincides with the entry into adulthood of the first generation of citizens born after the fall of the USSR, but also with growing interactions between international subcultures thanks to the Internet and the opening of national borders. In an effort to move beyond preoccupations with modernist architecture and Soviet nostalgia, projects like the Calvert Journal, New East Cinema and New East Photo Prize were conceived with the aim of mapping out an aesthetic consciousness capable of uniting former socialist countries.

Leaving behind East-West dichotomies, these and other depoliticized platforms permitted emerging photographers, musicians, directors, and stylists — many of whom grew up during the transition period — to try their hand at reconfiguring an outdated signifier through artistic means. At the same time, the Anglophone cultural landscape is experiencing an upsurge of artistic production dealing with conceptualizations of identity and belonging, helping to build a new perception of Eastern aesthetics.

The Calvert Journal has been an incredible success, winning several prizes since its 2013 launch — yet it was not immune to criticism. Despite efforts to dismantle prejudices about the former Eastern bloc and allow years of neglected cultural production to reach vast audiences across the world, the Calvert Journal was taken to task for taking on the myth of the "failed Soviet experiment," exploiting younger generations’ fascination with the unknown for clicks. In 2016, the Calvert Journal even published a warning to Internet users against the thoughtless sharing of decontextualized images — in this case, the "concrete clickbait" of "mysterious" spomenik monuments, which are scattered across the former Yugoslavia.

If avoidance of politically sensitive topics could be explained as a way to avoid detracting from the more art-focused mission of projects like Calvert, the same cannot be done with the problematic replacement of the term “post-Soviet” with “New East.” In a 2018 article for Russia Beyond the Headlines, Daniel Chalyan argued against this usage, pointing to the risk of moving from one stereotype to another. As a brand, the term "New East" becomes yet another readymade marketing tool of the neoliberal West, a repackaged "post-Soviet" concept for a new generation of consumers.

Citing the indifference of Western public opinion toward many of the Soviet Union’s successor states, British branding expert Wally Olins, writing in 1999, had already cautioned against renaming the entire region as if it were a single entity. Subsuming a diverse set of young nations working to forge individual identities under the umbrella of the “New East” just because they share a common past could lead to negative branding and marginalization. Olins wrote:

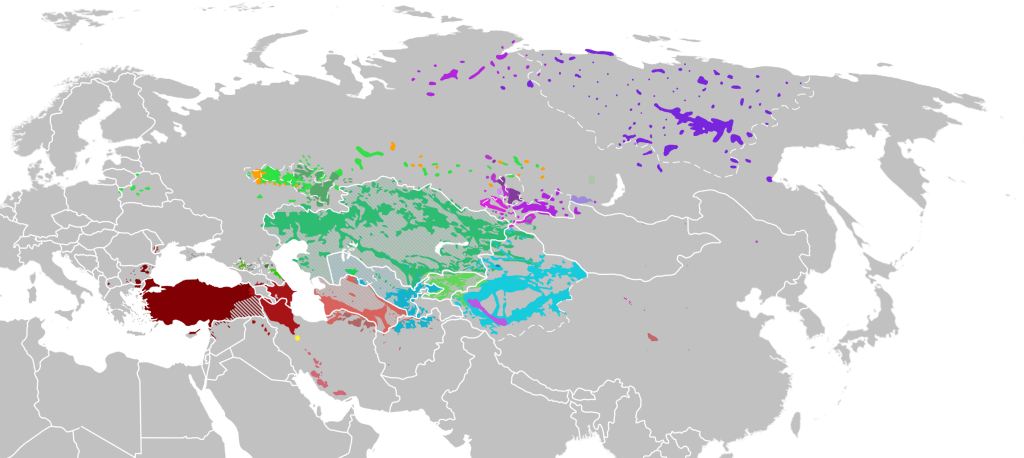

How many people—apart from real specialists—can tell the five former Soviet Central Asian ’stans’ apart? (...) Some large, some small, some have huge resources, others don’t, some are old-style communist dictatorships, others are evolving in a more or less democratic direction and, of course, they all dislike each other. But they’ve got a real problem in establishing who and what they are in a world increasingly cluttered with ‘new’ nations.

Even if many of the projects dealing with the “New East” are transnational and interdisciplinary in form, colonially charged motifs may permeate the collective unconscious. Despite occasionally running critiques like “Beauty and the East: Is it Time to Kick our Addiction to Ruin Porn?”, the Calvert Journal continues to hype a dynamic "New Eastern" culture, turning anonymous Eastern European cityscapes into exotic destinations seemingly begging to be visited, photographed, and shared on social media.

Once representations of pure functionalism, disused khrushchevki have found new life as subjects of Instagram posts by hipsters hungry for Brutalist design. The concept of a unitary "New East" photography, music, and cinema assumes the existence of a common aesthetic, discouraging listeners and viewers from considering each photo, song, or film on its individual merits. Similarly, once post-Soviet avant-gardes were introduced into the Western fashion scene, fast fashion brands like H&M and Urban Outfitters immediately picked up the trend, making a mint on t-shirts and sweaters covered in Cyrillic letters. Even activist groups like Pussy Riot are victimized by the commodification of the "Eastern" aesthetic, which absorbs their performances into a depoliticized global pop culture.

"Place branding" is a powerful tool that works perfectly for businesses seeking to attract investors and create jobs. However, as in the case of Calvert, we often find evidence of a soft political strategy operating behind a "purely aesthetic" "New-East" facade. Knowing that Western audiences are eager to accept the transformation of political symbols into consumer objects, we may feel a justified skepticism toward contemporary artists working within "New East" frameworks — and toward the venues that amplify their voices.

Clearly, "made in the East” artistic production has found its market. Yet we should continue to interrogate the relationship between the "New East" and the reality it claims to represent — a reality whose roughness, complexity, and diversity resists smooth salesmanship.