Kevin M. F. Platt is Professor of Russian and East European Studies and Chair of the Doctoral Program in Comparative Literature and Literary Theory at the University of Pennsylvania. He is author or editor of a number of books, including Terror and Greatness: Ivan and Peter as Russian Myths (Cornell, 2011), Global Russian Cultures (Wisconsin, 2019), and, most recently, Border Conditions: Russian-Speaking Latvians Between World Orders (Cornell/NIUP, 2024). His current project is entitled Cultural Arbitrage in the Age of Three Worlds.

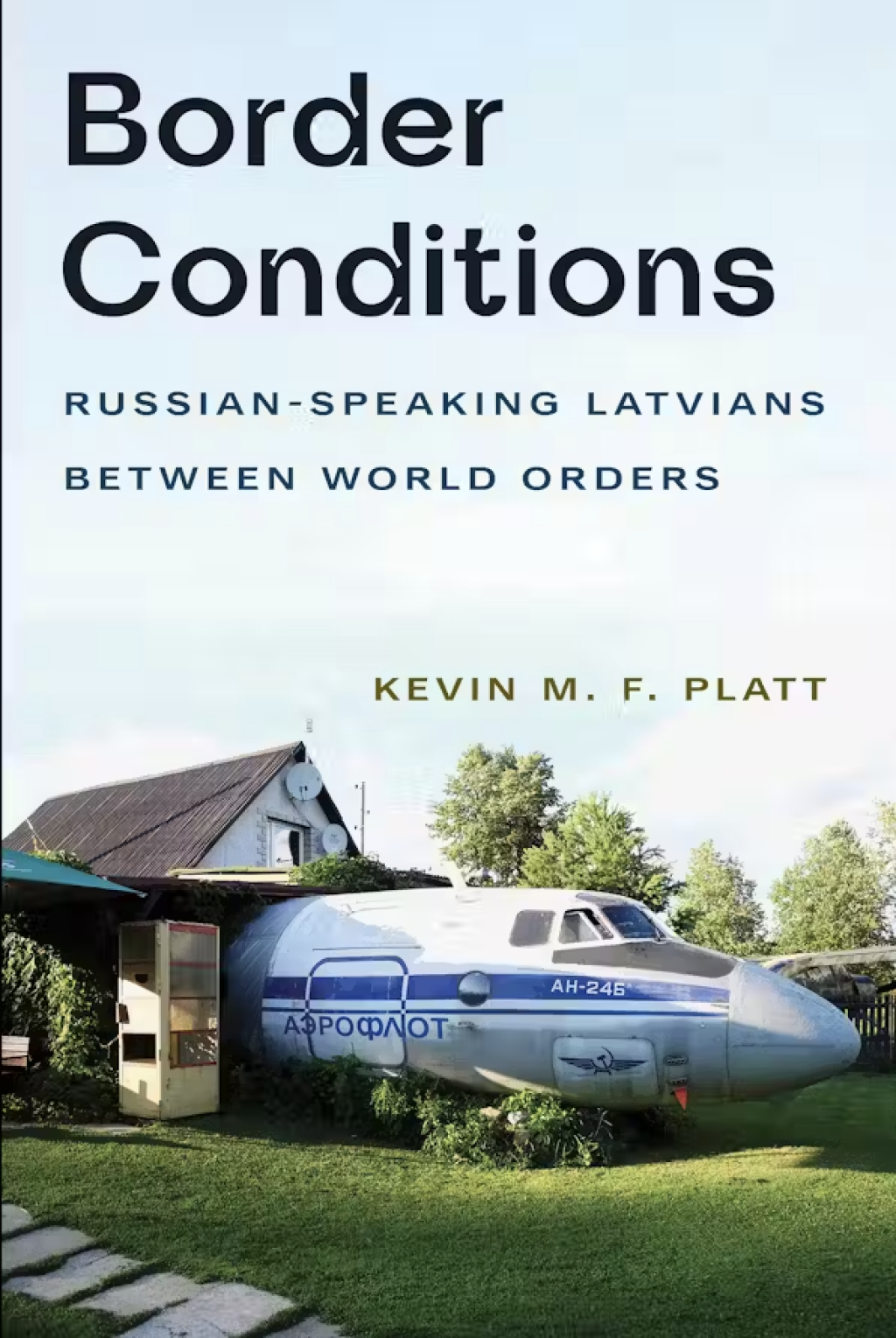

This post is an excerpt from Border Conditions: Russian-Speaking Latvians between World Orders by Kevin M.F. Platt, published by Cornell University Press. Copyright (c) 2024 by Cornell University. Used by permission of the publisher.

This post is Part I in a three-part series; Parts II and III will appear on 4/24 and 4/25, respectively.

Passports are constructed from paper, power, and glue. All three components are liable to give out, in time. In late 1991, some 287 million people became the holders of a defunct state’s passport. Liberated from the political order that had defined, for better or worse, past official identities, each former Soviet citizen faced existential questions of political belonging, identity, and geography suddenly yawning open before them. An intensive period of political invention, economic competition, violence, and demographic resorting followed across Eurasia. For some, and in some regions, these processes quickly or slowly found a resolution. For others, questions are still open more than three decades later. The new era presented a particular set of challenges to Russians and others who identified with Russian language, culture, and identity outside the Russian Federation. For the national majorities of the former Soviet states—especially in Baltic republics such as Latvia, the focus of this book—the Soviet collapse was a rebirth of national sovereignty and independence from an illegitimate, authoritarian domination. Notwithstanding the hardships of those years for all, that experience of national redemption was buttressed by hegemonic accounts of the historical significance and justice of the Soviet collapse, emanating from the ascendant liberal Western order. In contrast, Russians in the non-Russian republics, regardless of their stance toward Soviet power or its sudden vanishing, lost their privileged status of being “at home” everywhere in the USSR—a status often hardly acknowledged by the Russians themselves, yet patently illegitimate in the eyes of many of their non-Russian neighbors, and especially from the perspective of Baltic peoples such as the Latvians. Overnight, Russians here found themselves cast into an unsettled historical and geographical border condition.

Latvia’s Russian and Russian-speaking population is a legacy of empires—quite literally so, in the case of the large number who arrived in this region during the Soviet era. Many of them, as is illustrated by their continuing orientation toward the media and public life of the Russian Federation and alienation from the social and linguistic realities of independent Latvia, have been unable to turn away from the political imaginaries and geographies of that past. As tensions have risen over the past decades concerning the Russian Federation’s projections of power and violence into neighboring states, this population—suspended between European, Latvian, and Russian cultures and worlds—has more and more come to be regarded as alien, potentially threatening to the social body, a fifth column. As I will discuss in greater detail in chapter 2, Latvian speakers have often referred to Russians here as okupanti (occupiers), a term that has gained new resonance in the shadow of Russia’s 2022 invasion and occupation of Ukrainian lands, as the clamor of threats, burdens, and stigmas of the imperial legacy have reached a crescendo in Eastern Europe. In the words of Latvian president Egils Levits concerning those Russian Latvians who support, or do not oppose, Russia’s war, they are a social segment “disloyal to the state” that must be “isolated from society.” Or as one ethnic Latvian acquaintance casually and cuttingly informed me in July 2022, “Russians aren’t even really Slavs—they aren’t Europeans at all. They’re Asians.” A friend, an ethnic Russian from Ukraine who is married to an ethnic Latvian and resides in Riga, added (in Russian) that the Russian invaders of Ukraine are quite simply a “horde” (orda)—a term that evokes accounts of the Mongol conquest of Slavic lands in the medieval era.

But hold on a moment. In full recognition of the overt imperialism and criminality of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, we must ask: Don’t these last formulations reproduce a different imperial gaze—that of the Orientalizing view to the east from Europe? Adding a further twist, while my acquaintance’s remark may be seen as straightforwardly Eurocentric and racist, my friend’s condemnation of the Russian “horde” is redolent of the Russian imperial historical mythology concerning the Mongols—a Russian redaction of a Eurocentric, Orientalist geographical vision. The imperial violence that looms over Eastern Europe seems to originate, for these voices from Latvia, from all directions at once. Is this Russian imperialism, plain and simple? Is it an alien imperialism of the East? Is it an archaic resurgence of European imperialism, which Russia learned from the West? Could Russian belligerence be a response to European imperialism, part of an ongoing confrontation between the West and the Rest, as Russian voices claim, and as others across the world appear to concur? The intersecting imperial legacies and perspectives that collide in the Russian border condition in Latvia are multiple, distinct, certainly incommensurate, yet also contradictory and intertwined.

Yet beyond echoes of empire, fears of Russia’s new imperialism, and Orientalizing responses to it, we should also recognize in the presence of Russians and Russian speakers in Latvia the afterimages of dashed hopes for other geopolitical orders, based on peace and amity. From Washington to Brussels to Moscow, the decade following the collapse of the USSR seemed to hold out the promise of a world of increasing mobility and cohesion between “free-market democratic societies,” as they were called then, all across Eastern Europe and inclusive of the Russian Federation—a new reality in which the geographical impropriety of Latvia’s Russian population would fade in significance as the border zone itself progressively lost meaning. The failure of that world to take shape is among the topics of this book. Yet that is not the only failed scheme for peace that haunts this region and population. Somewhat earlier, in the late 1980s, as the Berlin Wall was being demolished and Cold War borders were opening, Mikhail Gorbachev invoked his own, distinct conception of a vast “common European home,” inclusive of territory from Paris to Vladivostok—a vision that “rules out . . . the very possibility of the use or threat of force.” That vision, predicated on the presumed persistence of the USSR, foundered on its disintegration, which was already being demanded in mass protests in Latvia at the same moment the Soviet leader pronounced these words in 1989 before the Council of Europe in Strasbourg. In the wake of Gorbachev’s death in 2022, Latvian voices were among the least celebratory—less inclined to remember him as the architect of military withdrawals and plans for peace than as the man who unleashed Interior Ministry forces in Latvia and Lithuania in an abortive and bloody attempt to reassert Soviet control in early 1991. Yet finally, buried beneath that violence, the looming memory of Stalinist mass crimes, and the banal inhumanity of the Soviet experience, which are at least as evident from the perspective of Latvia as from any other, lie aspirations for a global peace underwritten by socialist internationalism. Despite the cynicism with which they were often deployed, those aspirations were a source of inspiration and a resource for resistance against injustice for people and movements across the globe during the twentieth century, who saw the socialist world as an ally standing with them against capitalist imperialism and neocolonialism—once again in the mode of the opposition of the West and the Rest. The border condition of Russian and Russian-speaking Latvians, in sum, attests to serial, intertwined, and contradictory histories of both failed empires and failed peace plans. There, we face the urgent question: Can hope be salvaged from those histories at present?

In a central segment of Negative Dialectics, Adorno offers a critique of the Hegelian dialectics of history, in which the violent clashes and ideological contradictions of historical events are ultimately legitimated and regulated by the greater logic of the progress of the world spirit. In this regard, it may be apt to recall that both the adepts of Marxism-Leninism, in its day, and many key frontmen of Western hegemony following the Cold War have been heirs, in distinct ways, to Hegel’s faith that history’s transcendent ends explained and legitimated its contingent collateral damages. In contrast, Adorno asked what we can make of history’s contradictions and bloody clashes in the absence of an idealist philosopher’s certainty in supervening unity and purpose. Rather than breathlessly anticipating a just resolution and a coherent synthesis, we are left to contemplate the etiology of contradiction: “Dialectics is the self-consciousness of the objective context of delusion; it does not mean to have escaped from that context.” The Russian border condition is one location where the objective context of delusion, the contradictions at the core of global contestation over power, money, and territory in the twenty-first century, become palpable. The global history of the late twentieth century, as conceived in contemporary political discourses, founding national and civilizational myths, and history books alike, is defined by two supervening axiological distinctions: the ideological and geopolitical conflict between state socialism and liberal capitalism, on one hand, and the great drama of the decomposition of European world empires, the complex processes of decolonization, and continuing contestation over legacies and aftereffects of empire, on the other. These processes intersect and overlap yet fail to mesh and cohere in Eastern Europe, in Latvia, and especially in the Russian border condition. As I explain in what follows, critical examination of the incommensurate historical legacies of Eastern Europe reveals that these alternate dimensions of history, memory, and actuality are radically out of sync and, further, that this lack of synchronicity has resulted in a blockage of paths toward historical consensus and political comity, not just here, but in many places across the globe.

Comprehension of this broadly shared condition demands a consideration both of local histories and of deep critical and ideological prehistories, tracing, on one hand, the intersection of imperial and ideological categories of analysis from the end of the Cold War, through the decade of history’s “latency” in the 1990s, to the accelerating inquiry into the intersection of postsocialist and postcolonial categories in the academy, and, on the other hand, the steadily increasing drumbeat of “memory wars” in the geopolitics of the postsocialist lands. These processes, developing in parallel, have both come to a culminating point in the past several years: scholarly discussion of postsocialist postcoloniality has reached a new level of global coherence in recent publications on the transnational history of socialist anti-imperialism, and memory war has led to real war, signaling a new era of systemic antagonism between Russia and its former colonial subjects, as well as between Russia and the West. War generates an insistent demand, addressed to all, to choose sides. We must condemn Russia’s war of aggression without equivocation. Yet, as the above suggests, the terms in which we formulate our condemnation possess a prehistory and present meaning that extend far beyond our familiar terrain and authoritative definitions. Recognizing the risks involved, in what follows in this chapter and throughout this book, we will dwell in the Russian border zone. There, under the overhang of failed empires and failed peace plans, one encounters a local space of contradiction that grants critical traction on the preconditions of geopolitical conflict today.