This week, All the Russias will be running a four-part series of excerpts from Emil Draitser’s new book, In the Jaws of the Crocodile: A Soviet Memoir, out this month from the University Press of Wisconsin. The action in the chapter takes place in September 1974, at the height of the Soviet Jewry Movement in America and worldwide. This book is the the sequel to his memoir titled Shush! Growing up Jewish under Stalin and the prequel to his autobiographical novel, titled Farewell, Mama Odessa, excerpts of which appeared in our Winter Reading Series in January 2020.

An exclusive virtual book launch will take place on Wednesday, February 3, 6:30 PM EST at the Shakespeare and Co. Bookstore in NYC. Sign up here.

Emil Draitser is an author and Professor Emeritus of Russian at Hunter College in New York City.

This is Part III in a four-part series. Parts I and II may be found here and here, and Part IV will follow on Friday, 1/29.

Chapter 24. A Small Iron Door in the Wall (Continued)

What else do I have in my briefcase? Ah, a short piece titled “The First Dialogue.” I wrote it recently, recalling one of the Voice of America broadcasts I was able to catch. Some time ago, a certain American professor advanced the hypothesis that Russians endure tyranny and are used to oppression because they swaddle their infants too tightly. The babies grow up accustomed to an inhibited life and the lack of freedom from a very early age.

I imagine a swaddled baby boy who can talk right after being born. Since he doesn’t expect much fun in his life, the infant asks his parents to give him a good reason to go on in the world they’ve brought him into. They respond with the propaganda line that it’s an upstanding citizen’s duty to “fight for the happiness of the future generation of Soviet people.”

“Oh, that calls for a standing ovation,” the swaddled baby chuckles. “Sorry I can’t oblige you, folks. My legs don’t hold me up yet, and my hands are all tied up. Not much room for applauding.”

Well, the spook shouldn’t give me a hard time about this piece. I’m about to leave the country on my own will. This alone says loud and clear where I stand politically.

What else? Oh yes, there’s another piece I wrote “for the desk drawer.” It’s titled “The Art Critic.” This one could get me into hot water. The story pokes fun at the same organization that has snagged me out of the embassy line and keeps me waiting in this stone cage. In urban folklore, an “art critic” is a nickname for a KGB plainclothesman. When they send a Soviet artist abroad to show the superiority of socialist art over rotten bourgeois art, a KGB agent accompanies him as an “art critic” in case the artist tries to do something funny, like asking for political asylum.

The piece could spell big trouble for me. For a fact, I know the major will get offended. It’s not too difficult to see that the things in the art critic’s briefcase in my story are ominous emblems of life in the gulag. All of them! A loaf of bread . . . an aluminum cup . . . and whose portrait could that be in the KGB guy’s briefcase other than that of the fierce founder of the Soviet secret police, Felix Dzerzhinsky?

The thought makes my blood curdle. Over my whole Soviet life, I’ve been lucky not to get into the paws of the secret police, and here, on my way out of the country, they’ve gotten me. May I be damned! Why, I ask myself, didn’t I think twice about what to put in my briefcase? What a dupe!

Then I remember Squirrely’s battered briefcase . . . I realize, before I had composed the piece, I knew the spooks carried worn-out briefcases to resemble intellectuals. It looks like I had forgotten about it.

I look at Squirrely. He stares at the ceiling. He’s bored to death hanging around in the caretaker’s lodge with a detainee for hours on end.

Finally, the door opens and a man about my age, in his mid-thirties, appears on the lodge’s threshold. His straight blond hair moves from side to side across his forehead every so often. Light-blue, bulging eyes, plumpish lips . . . a familiar face. Where have I seen this man? Well, but of course! The same well-tailored suit, a stylish nylon shirt complete with malachite cufflinks, the same light-blue, bulging eyes . . . Ha! The café at the House of Journalists! I’ve seen him over there. He hung out there often! So, he’s an operative attached to the journalist brethren.

But wait, where else have I seen him before? Suddenly I remember. About ten years before seeing him at the café, at the start of my literary career, I’d attended a few sessions of a young writers’ group affiliated with the newspaper Moscow Komsomol Member. And there, among others, was this blond man with the bulging blue eyes. I guess that if he himself wasn’t an “engineer of human souls,” as Stalin nicknamed Soviet writers, then he was at least their supervisor.

At the meeting, he introduced himself to the group as Leonid. Now, this man sits in front of me on a stool that Squirrely has offered him, wearing a suppressed Mona Lisa smile on his lips (that is, the smile earmarked for use at the café of the House of Journalists).

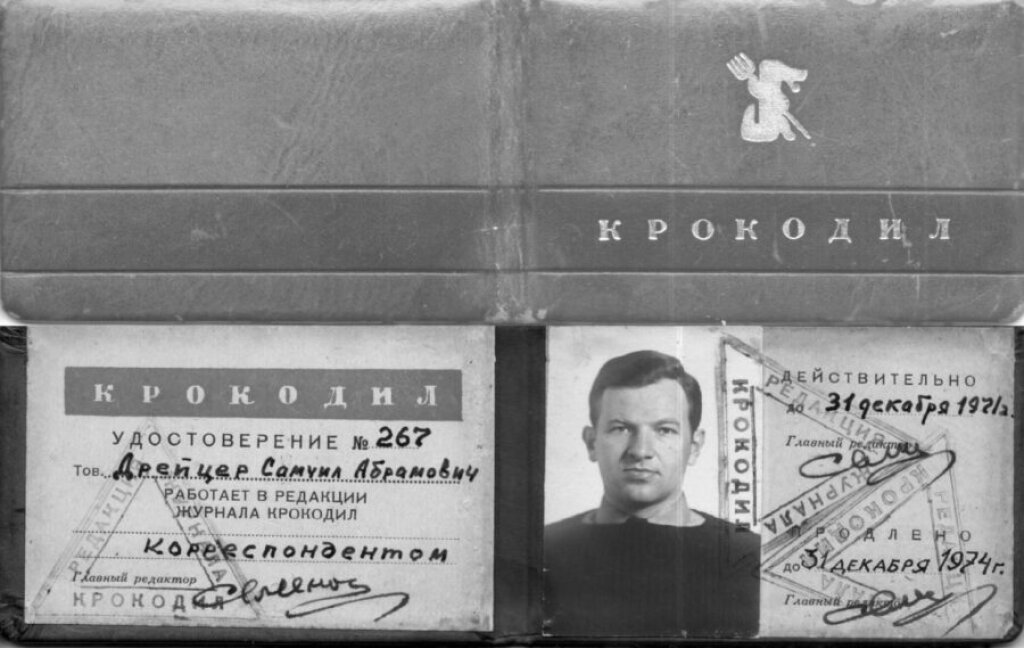

Squirrely takes a position at the entrance, his arms crossed as if to remind me again: “Abandon all hope, ye who enter here!” Leonid flashes his burgundy leather-bound ID, confirming he’s a KGB major. In stark contrast to the face he has used in the café, the one in his ID is unsmiling. (In all my Soviet IDs, I have the same somber, depressed facial expression, the kind you expect to see in American mug shots. In the Soviet Union, it was assumed that smiling faces have no place in official documents!)

What do you know! A KGB major, to boot.... Maybe if he were some lieutenant, I would have some hope. Perhaps, I’d wriggle out of the situation somehow.

In what I can only imagine was an attempt to prove that his ID picture was of him and not of someone else, Leonid wipes the Mona Lisa smile from his lips. It is almost as if he said, “I’m not some customer at the House of Journalists café. I’m a KGB major carrying out my duties of national importance.” The phrase he utters makes it clear: “Well, young man. Let’s see what you have tried to smuggle into the embassy of a foreign power.” As if I were having an out-of-body experience, I wonder to myself, since when has Holland become a foreign power? Well, the USSR is a state power, all right. According to Soviet propaganda books, there are also imperialist powers—America, Great Britain, and France. But Holland, a country the size of a Moscow region? It’s clear that the spook uses the term “power” to underscore the gravity of my alleged crimes. “An attempt at smuggling sensitive documents into the embassy of another country” seems dangerous enough, but “smuggling documents into the embassy of a foreign power” should make me shake in my boots. Well, what about a state like Liechtenstein? Or Luxembourg? There is also Monaco, where they have casinos in Monte Carlo.

I reply with a shrug: “Well, some sketches and notes.”

Leonid also shrugs.

“What for? Over there,” he utters, “nobody cares about all this stuff. It’s a different world out there. . . .”

He says it in a hopeless tone, one unbefitting an interrogator, and looks not at me but somewhere off into the distance. It seems like, at some point, he may have toyed around with the same idea for himself. To leave behind his previous life, to cross over into the world on the other side of the Soviet border . . .

It may sound strange, but, for a moment, the fact that the spook confirms my doubts calms me down. Really, why did I schlep all these papers nobody, but myself cares about to the embassy?

From In the Jaws of the Crocodile by Emil Draitser. Reprinted by permission of the University of Wisconsin Press. © 2021 by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System. All rights reserved.