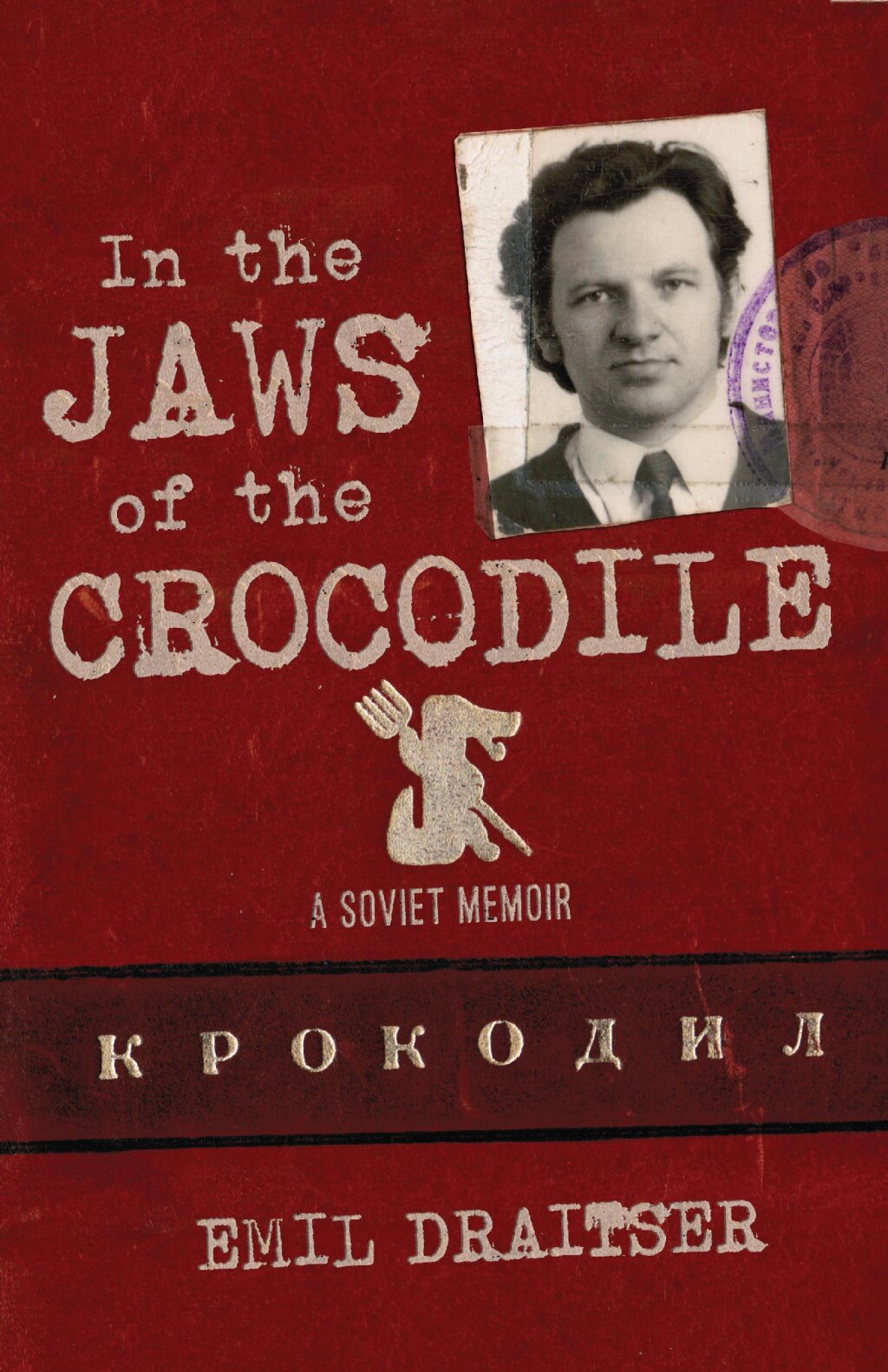

This week, All the Russias will be running a four-part series of excerpts from Emil Draitser’s new book, In the Jaws of the Crocodile: A Soviet Memoir, out this month from the University Press of Wisconsin. The action in the chapter takes place in September 1974, at the height of the Soviet Jewry Movement in America and worldwide. This book is the the sequel to his memoir titled Shush! Growing up Jewish under Stalin and the prequel to his autobiographical novel, titled Farewell, Mama Odessa, excerpts of which appeared in our Winter Reading Series in January 2020.

An exclusive virtual book launch will take place on Wednesday, February 3, 6:30 PM EST at the Shakespeare and Co. Bookstore in NYC. Sign up here.

Emil Draitser is an author and Professor Emeritus of Russian at Hunter College in New York City.

This is Part II of a four-part series. Parts I, II, and III may be found here, here, and here.

Chapter 24. A Small Iron Door in the Wall (Continued)

Squirrely dumps my briefcase on some folding table, and Leonid rummages through my papers. My throat dries up at once. It tickles. I’m seized with anguish. To paraphrase Lensky’s opening line in the Eugene Onegin aria, “What does the coming day have in store for me?” Except now it’s the next minute.

Suddenly, it hits me that most of my papers are handwritten. They’re chicken scratch; they’re barely legible. To tell you the truth, sometimes even I have trouble deciphering my own writing. Who knows what I’ve scribbled there? Back in my school years, my father reproached me for my bad penmanship from time to time. He told me more than once it would do me a lot of good if I took the time to improve my handwriting. I’ve never gotten around to doing it for lack of time. And now, by sheer serendipity, that fault of mine may well save me from trouble. God willing, Leonid will not read “The Art Critic” or anything else that the authorities might find offensive.

My body stiffens as I watch the major. At first, trying not to lose the physical composure a major ought to have, he strains his eyes, squinting. Then, grunting, he raises one sheet after another to the dim light bulb hanging from the ceiling. With an annoyed expression on his face (an expression I can only assume is caused by the need to reveal his physical defect to a detainee), he pulls out a small eyeglass case from the inside pocket of his jacket. He opens it up and takes out a pair of horn-rimmed glasses resting on a blue velvet lining. Both the eyeglasses and the case are designed so elegantly it’s clear they are a non-Soviet make. I can’t help thinking, I bet he’s snatched them up from some foreign tourist while shaking him down under some pretext.

The spook puts on his glasses. I freeze. He hacks, clears his throat, and hacks again. It looks like his glasses are useless. Unable to make any sense of my papers, irritated, he throws them back on the folding table. His face assumes an angry and disgusted expression, the kind a dog wears while it sniffs a brand-new galosh that still reeks of rubber. I sigh in relief. It looks like I’m in the clear. Leonid turns to my other papers, the ones I have typed up on my Olympia typewriter. I’m not worried about them. I’ve typed up only the pieces I thought about showing to some editor. There is no subversive material there. Leafing through them for a while, Leonid pounces on a piece titled “An Open Letter.”

As I understood later, the stool pigeon’s single task was to weed out anyone who carries protest letters or pamphlets. Refuseniks’ struggle for the right to emigrate was already at its height. Publicity was their only weapon in fighting human rights suppression.

The spook reads this “open letter” piece. But I couldn’t care less. What he’s reading is just a draft of one of my lampoons that didn’t make it to print. In that piece, I used the format of an open letter as an ironic device. If my memory serves me right, it was something like an open letter written by the director of one of the Black Sea resorts, in which he reveals that he has taken bribes from vacationers he accepted into his establishment.

The officer sifts through the rest of my papers. He finds nothing incriminating. Frustrated by this waste of his time, he gives me a disapproving look and declares: “Well, if you want to take all this stuff out of the country, you should take your papers to the Glavlit and get their permission.”

With that, they let me go. The major leaves the lodge, and Squirrely tags along behind him, mumbling and wearing a rueful countenance.

My legs made of gelatin, still not having processed that I got off with only a scare, I walk down Suvorov Boulevard. I pass the House of Journalists and, trying not to jump for joy, I head to the Nikitsky Gate train station. I go home.

On the train, I check behind me every so often to see whether I’m being followed. I get my first breath of fresh air when I exit the train. The danger is over. . . .

My encounter with the KGB in the Dutch embassy courtyard wasn’t my last run-in with the frightening agency. Before I boarded my plane at the Sheremetyevo International Airport, a customs official—a tall, unsmiling man of about forty—rummaged through my suitcases and came upon my scrapbooks. Since I’d had trouble finding any decent ones in Soviet stationery stores, an acquaintance of mine, a bookbinder, made them to my specifications. The scrapbooks were large, a foot and a half long and a foot wide, their covers upholstered with a dark-green cloth. I filled their pages with clippings of my work that had appeared in papers and magazines throughout my writing career. I had no specific reason for doing this. I just wanted to have some keepsake, some memento of that volatile part of my life when my excitement was often followed by disappointment and joy by frustration.

On the eve of my emigration, I was convinced I should say farewell to my writing life once and for all. I was sure that leaving the country where my native tongue was spoken meant I would never take to my pen again.

The customs official showed no emotion when he discovered my scrapbooks. In a business-like manner, he pulled them out of the suitcase, placed them on one of the inspection tables, and pressed a button. Soon, through the side door of some makeshift partition, a uniformed KGB lieutenant in his mid-twenties emerged. He approached the inspection table and, without even looking at me, scanned my scrapbooks, page by page. It seemed the officer tore out my clippings randomly. He crumpled them in his fist and threw them into the nearby wastebasket.

When he finished, he returned my half-torn scrapbooks to the customs official and, in the same way as before, without ever looking at me, walked away and disappeared behind the same partition through which he had emerged. My stomach empty, I felt violated and robbed, as if the KGB man had torn out and crumpled up pieces of my past life.

Yet, his actions didn’t surprise me. All throughout my Soviet life, I had gotten used to the fact that the authorities, especially those representing the most formidable agency, can do whatever they feel like doing to you. The only thing seemed to be odd was the KGB officer didn’t tear out all my clippings, one after the other, but he did it selectively.

Most of the torn-out materials have consisted of my satirical pieces published in Lenin’s Banner, a regional Moscow newspaper. He also destroyed a few other articles—from Crocodile, from Izvestia, from Komsomolskaya Pravda. But he did it randomly, apparently, out of sheer spite, just to annoy me.

So, it was strange. Why the hell had he cared so much about my pieces published in Lenin’s Banner?

It took a long time to get to the bottom of that mystery.

From

In the Jaws of the Crocodile

by Emil Draitser.

Reprinted by permission of the University of Wisconsin Press. © 2021 by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System. All rights reserved.