Angelina Lucento is an Assistant Professor of History and Art History at the National Research University Higher School of Economics

Long before post-industrial capitalists began to harness this concept for the sake of profit, Aleksei Gastev (1882-1939) understood that the future of labor would depend not on the mass production of goods, but on the life energy of the human body. The recent exhibition Gastev: How to Work at Moscow’s Na Shabolovke Gallery, curated by Aleksandra Selivanova, reveals the results of Gastev’s ingenious analyses of the relationship between the energetic matter of the human body and labor processes, many of which remain strikingly relevant today. The exhibition also explores the contributions his Central Institute of Labor [TsIT] made to the development of Soviet socialism.

The exhibition began in the gallery’s small foyer, where the curator and her assistants hung an extensive timeline of Gastev’s life history. It showed that he was not only an avant-garde poet and theorist of life and labor, but also that he had been a committed political activist since 1900, when he joined the Russian Social-Democratic Labor Party [RSDRP]. Most importantly, the timeline revealed how, during his time as a political exile in Paris, Gastev’s experiences as a factory machinist and union organizer catalyzed his obsession with the role of industrial labor in socialism. It also underscored how his worker status helped him enter into the nascent institutions of the post-revolutionary Bolshevik government.

Transitioning from the foyer into the main exhibition space, exhibition visitors encountered the first section of the main display, which was devoted to both Gastev’s role in Proletkult and his avant-garde poetry. Selivanova's careful selections of theoretical texts about industry and socialism, avant-garde drawings, and journal issues from Proletkult's activities during War Communism demonstrate that the movement emphasized creative activities as a means for understanding life in the new, post-revolutionary world. The poems Gastev wrote as a member of Proletkult reveal that he used poetry to explore the emotional experience of industrial production processes, examining how the energies inherent in the these psycho-physiologic affects might be harnessed to optimize worker productivity for the sake of socialism.

The section on poetry and creativity gave way to displays of polemical texts written in response to Gastev’s ideas, as well as photographs describing his international connections. These objects indicate just how influential Gastev’s plans to revolutionize industrial labor became in the 1920s and 1930s, not only in the USSR, but also in cities like Prague, Berlin, and Stockholm.

The photos and texts on Gastev’s international reach flowed into the exhibition’s final wall display, which focused on the work of the Central Institute of Labor [TsIT] and Gastev’s cumulative theory of the Scientific Organization of Labor [NOT]. This display brought the exhibit to a logical conclusion. The texts and documentary photographs that Selivanova selected from TsIT’s history revealed how the political clout Gastev gained in the immediate wake of the Revolution made it possible for him to become the head of TsIT, a Bolshevik institution devoted to the study of the role of the human body — especially the energy of its nervous system — in all aspects of socialist production.

Sub-sections devoted to documentary images from TsIT’s different laboratories, including the photo-film laboratory, the pedagogical laboratory, and the physio-technical laboratory, as well as images and texts dedicated to lesser-known TsIT theorists like Leontii Byzov (who developed the institute’s theory of data visualization) and Ernest Drezen (who created a new theory of language based on production) showed the true scope of Gastev's ambitions for TsIT. The idea was to extend NOT's reach beyond work to everyday and creative life, creating a unifying and totalizing program that would organize not only Soviet labor, but also the lives of its socialist citizens.

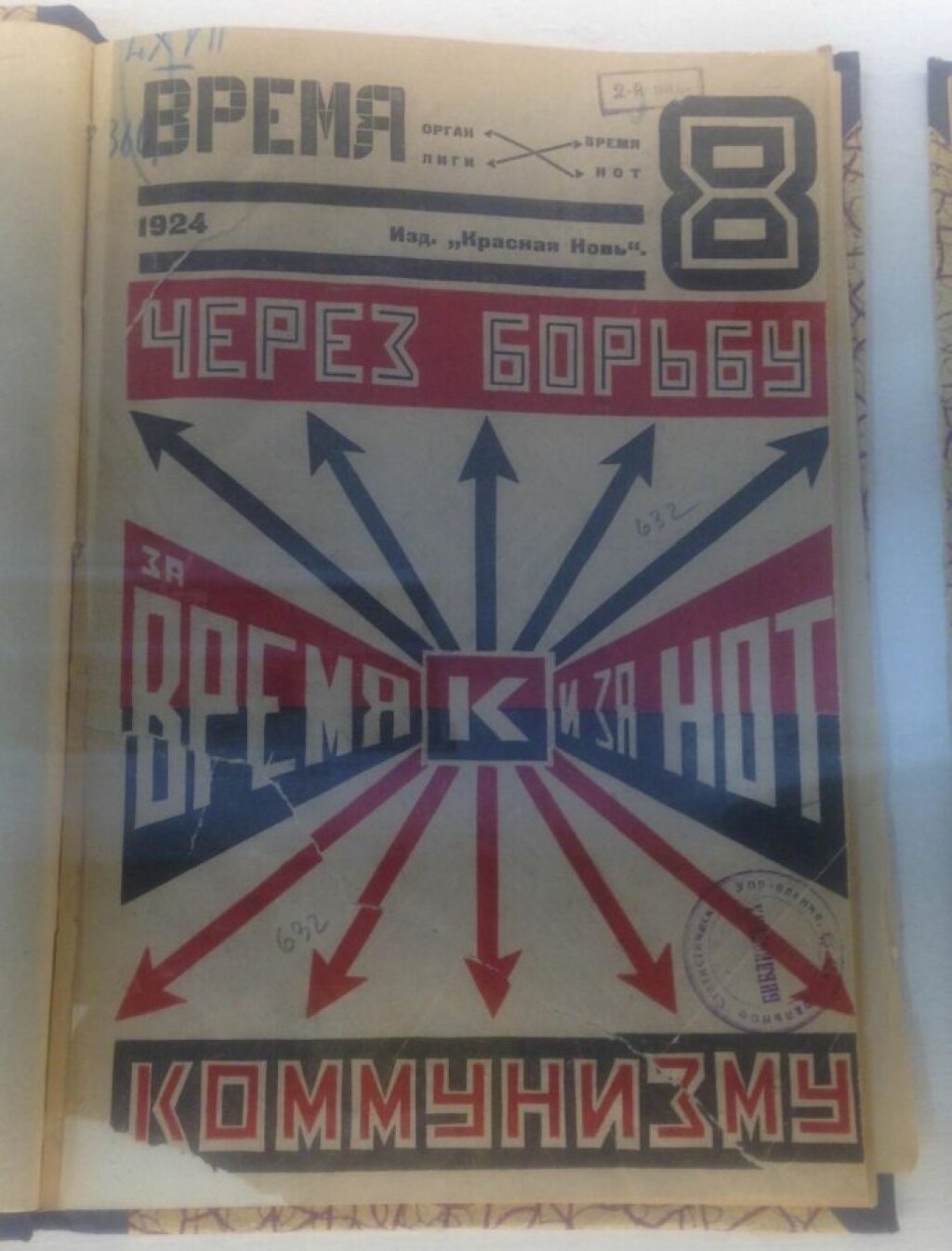

The inclusion of handwritten plans, sketches, and graphic design materials from two important avant-garde artists’ groups that existed within and around TsIT, namely Solomon Nikritin’s Projection Theatre and Platon Kerzhentsev's Time League, demonstrate the continued centrality of creative and artistic practices as central to NOT's evolution. In contrast to Gastev, who sought to treat the nervous energies of individual bodies as interchangeable components in an efficient machine, Nikritin was interested in each body’s unique energy as a product of its specific corporeal experience. In particular, Nikritin aimed to use theater to harvest the unique energies that emanated from actor and audience for the sake of the socialist collective.

On the other hand, Kerzhentsev's Time League focused on efficiency (Fig. 1). As the group explained in their “Temporary Regulations of the Time League,” their aim was to apply creativity and the techniques of the visual arts to “the struggle for the correct use and economization of time in all aspects of social and private life, as a foundational method for the actualization of the principles of NOT in the USSR.”

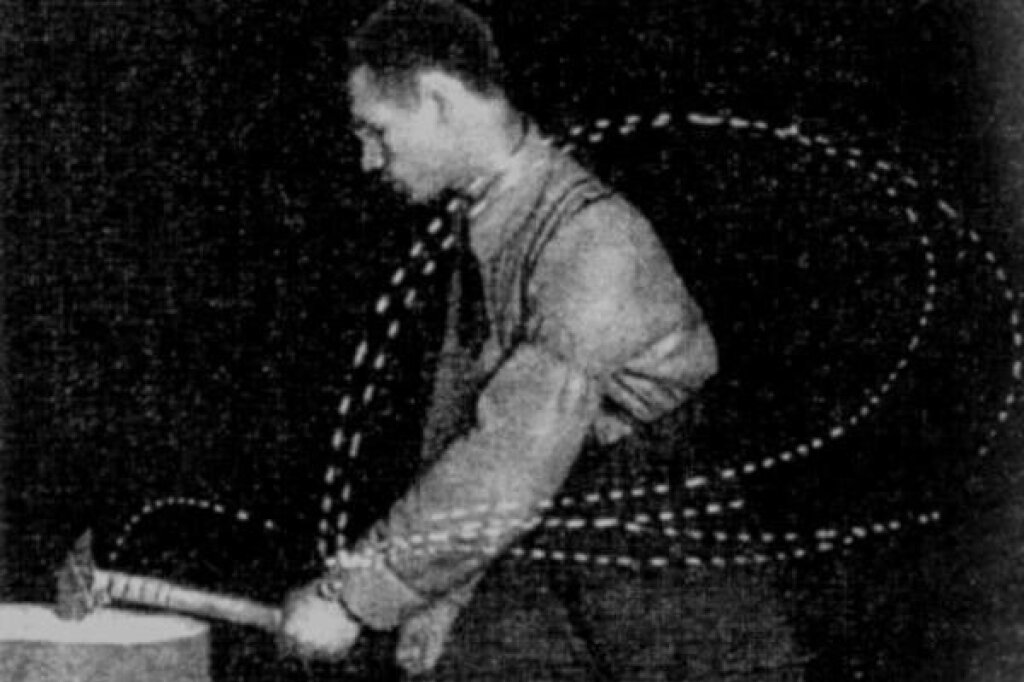

Gastev’s impressively detailed wall displays already ensured that the exhibition stood out among recent shows devoted to the avant-garde. What made it exemplary was Selivanova’s provocative centerpiece, an interactive display of reproductions of the apparatuses used to train workers in the ways of NOT. For example, visitors were encouraged to step into the confining shoe moulds used to train workers to assume the workbench stance that Gastev deemed the most energy-efficient (Fig. 2) and to insert their arms into a line of metal cylinders decreasing in size that were used to train the nerves and muscles of the elbow and wrist to hammer in the manner TsIT thought optimal.

Fitting one’s arms and legs into Gastev’s apparatuses produced uncomfortable, confining sensations, especially because one size certainly does not fit all. TsIT’s documentary images revealed that, when in use, the apparatuses, with their cinches and stops, resembled certain aspects of medieval torture devices (Fig. 3), which forced important questions about the contradictory role corporeal discipline and the drive toward conformity played in early Soviet efforts to rationalize labor, ostensibly undertaken in the name of socialist emancipation.

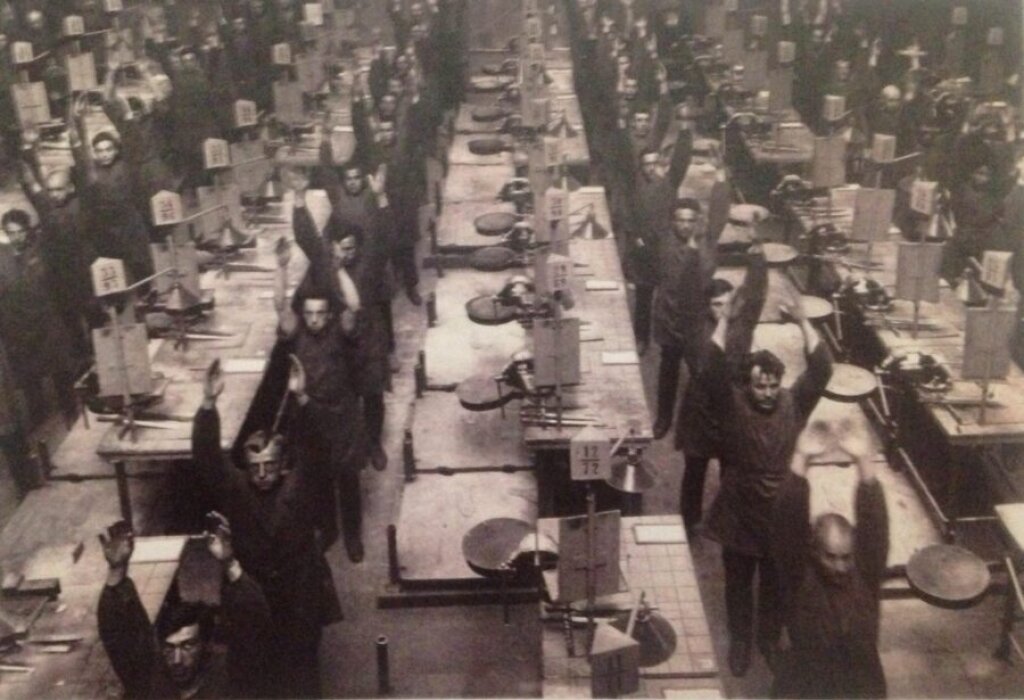

Gastev: How To Work revealed the innovative genius of a young, radical thinker, who until recently was all but forgotten by historians of art and culture. Gastev’s careful studies of the interactions between the electrical impulses of the human nervous system and the machines humans operate have never been more relevant. How To Work raised critical questions about the body's role in the exploitative networks of contemporary capitalism, in which bodies are perpetually connected to post-industrial digital devices that regulate everyday life and labor.

By revealing Gastev’s own interests in corporeal discipline for the sake of efficient productivity, the exhibition highlighted a perennial problem in studies of early Soviet culture, from the avant-garde to Socialist Realism: the contradiction between the desire for humanist unity and emancipation, on the one hand, and the embrace of capitalist strategies for control, discipline, and at times even violence, on the other. The exhibition's opening image of factory workers standing next to their workbenches, arms upraised in one of NOT's biomechanical exercises (Fig. 4) offers crucial insight into the direct experience of this problem.