Editor's Note: This week, All the Russias will be running a series of excerpts from Susanne Fusso's new translation of Sergey Gandlevsky's novel Illegible. The volume will be out from the NIU Press imprint of Cornell University Press on 15 November and will include the below introduction by Fusso.

Susanne Fusso is the Marcus L. Taft Professor of Modern Languages and a Professor of Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies at Wesleyan University, where she specializes in in nineteenth-century Russian prose, especially Gogol and Dostoevsky.

Sergey Gandlevsky (b. 1952, Moscow) is widely recognized as one of the most important living Russian poets and prose writers. He has won numerous prizes, including the Little Booker (best prose debut) for his “autobiographical novella” Trepanation of the Skull (1996). His novel Illegible (2002) was short-listed for the Russian Booker Prize and received an award for “affirming liberal values” from Znamia (The Banner), the journal in which it first appeared. In 2010, Gandlevsky received the sixth Russian national Poet prize, the most important prize for poetry in Russia, “for the highest achievements in contemporary poetry.” One Russian critic has called him “a magnificent lyric poet and artistic storyteller, one of the few knights of authenticity of feeling and purity of tone in contemporary literature.” Gandlevsky’s poems have been published in English, both in journals and in the collection A Kindred Orphanhood: Selected Poems of Sergey Gandlevsky, translated by Philip Metres (Zephyr Press, 2003).

The present edition is the first English translation of Illegible, Gandlevsky’s only work of prose fiction to date, though the novel has also appeared in German as Warten auf Puschkin (2006). In Russian, it was first published in a 2002 issue of the journal Znamia, though my translation is based on the text as it appeared in a 2007 volume. In contemporary Russian literary life, Gandlevsky’s stature as a poet is indisputably great; he is less well known as a prose writer, although his novels and essays have been critically acclaimed. For the English-speaking reader, contemporary Russian prose has been represented mainly in its fantastic, postapocalyptic, and dystopian modes. Gandlevsky’s novels display a more restrained, historically oriented literary sensibility, one that directs loving, sometimes bitter, but always keenly perceptive attention to the late Soviet and post-Soviet experience.

Gandlevsky has said that he dislikes “poetic” prose. He follows the model of Russia’s greatest poet, Aleksandr Pushkin, who in 1822 declared “exactitude and brevity” to be the cardinal virtues of prose, and who wrote stories and novels in a lucid, “classical” style, devoid of obviously poetic flourishes or ornamentation. But critics have noted that the structure of Illegible reflects a poet’s sensibility, with four parts that alternate in narrative point of view and time frame, on the model of a quatrain with an ABAB rhyme scheme. The first and third sections are a third-person narrative closely reflecting the point of view of Lev Krivorotov, a twenty-year-old poet in Moscow in the 1970s. As the story begins, Lev is involved in a tortured affair with an older woman, Arina, and is consumed by envy of his more privileged friend and fellow beginner poet Nikita, who is one of the children of high Soviet functionaries who were known as “golden youth.” Despite the third-person point of view, these sections feel almost like Krivorotov’s own diary, with running commentary on his hopes and desires. The second and fourth sections are narrated in the first person by Krivorotov thirty years later, after most of his hopes have foundered.

The name Lev, one of the most common Russian men’s names, means “lion” (analogous to English Leo), and the novel occasionally plays on the contrast between this noble appellation and the sometimes cowardly man who bears it. The last name Krivorotov evokes the phrase “twisted mouth” (krivoi rot), a facial expression of scorn and disgust. It also brings to mind the Russian expression “to twist one’s soul” (krivit’ dushoi), to speak disingenuously or act against one’s conscience. Both these meanings of the name are relevant to Krivorotov’s story. In both the third-person and the first-person narratives, Krivorotov recounts with regret and self-castigation the failure of a double infatuation, his erotic love for the young student Anya and his artistic love for the poet Viktor Chigrashov: “Lev Krivorotov had managed to fall in love twice in the course of a single week, and both times passionately. With a petulant woman of his own age and a middle-aged poet who bore the reputation of a living classic” (107). When this double infatuation becomes a romantic triangle, the consequences are tragic.

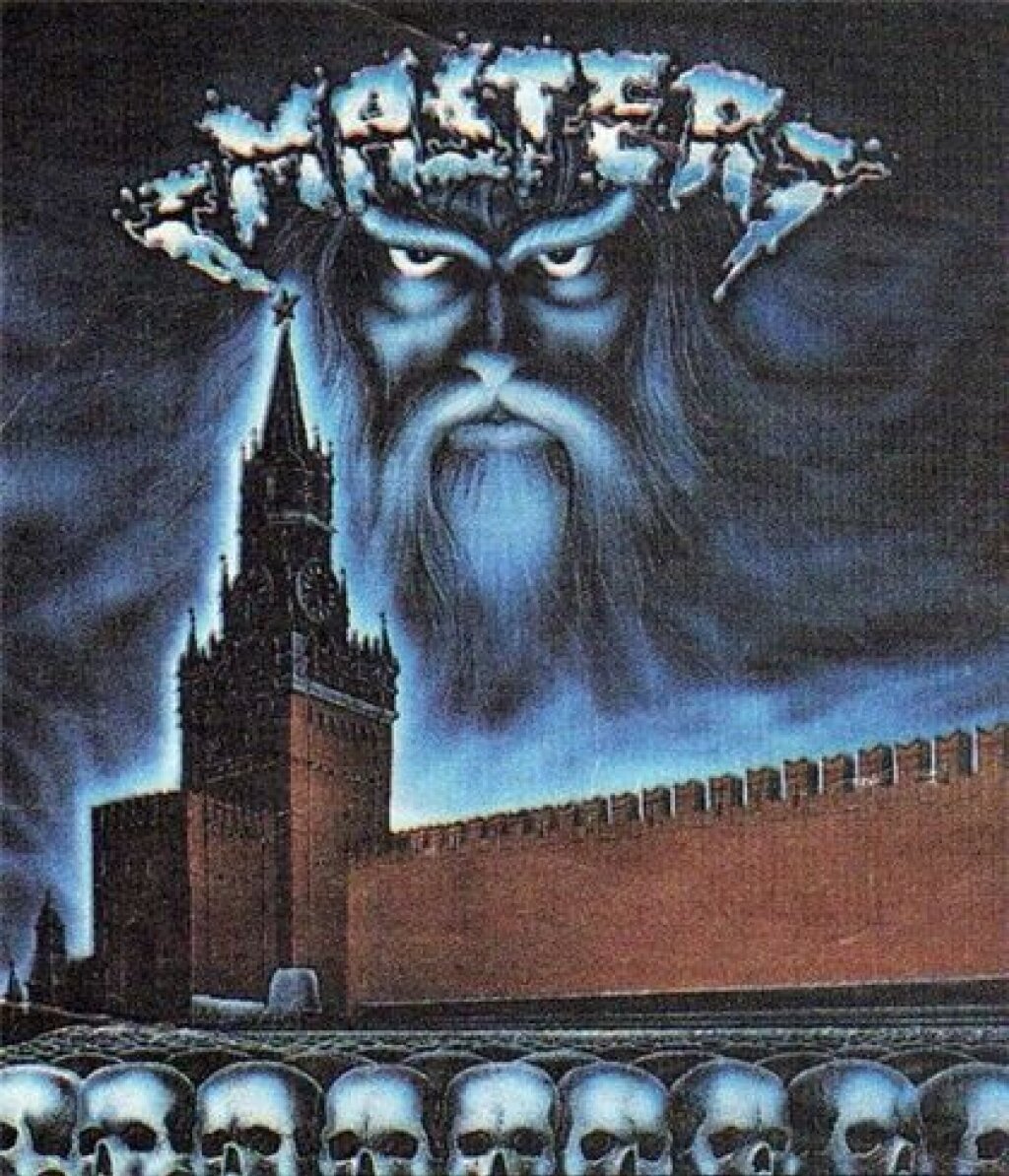

Reviewing the German edition of Illegible, Daniel Henseler writes, “The secret hero of the novel is not so much Krivorotov as Moscow bohemian life of the 1970s, which Gandlevsky depicts satirically and with an excellent sense of humor.” This is a milieu that Gandlevsky knows from the inside out. As the poet Alexei Parshchikov and the literary scholar Andrew Wachtel explain in their lucid introduction to the poetry anthology Third Wave (1992), Gandlevsky belongs to the generation of poets who emerged in the late 1960s and 1970s, who reacted against the public popularity of the poets of the Thaw, Andrey Voznesensky, Bella Akhmadulina, and Evgeny Yevtushenko. While the Thaw poets benefited from the brief period of relative freedom under Khrushchev, when they read their poetry to enthusiastic crowds in stadiums, “the poets of this new generation shied away from public and universal pronouncements, meetings in large halls, and public readings.” Parshchikov and Wachtel describe this choice as partly driven by lack of opportunity, but also as an aesthetic decision, “a conscious artistic reaction to the excesses of the previous generation.” They describe the new generation as producing “chamber music in contrast with their predecessors’ symphonies.” The new poets gravitated toward small groups, informal poetry clubs, and studios in which they could read their poetry to each other and issue their work in samizdat (“self-publishing,” usually typescripts with multiple carbon copies passed from hand to hand). As Parshchikov and Wachtel explain, the refusal to publish in official venues freed these poets from censorship as well as other potentially corrupting influences such as the need to cultivate mentors or to do assigned translations of poets writing in the other national languages of the Soviet Union.

Gandlevsky’s work was nurtured in several of these small-group venues. As a student at Moscow State University, Gandlevsky participated in the literary studio Luch (Ray of Light), which had been founded in 1968 by the scholar Igor Volgin (and continues to this day). In 1972, Gandlevsky and his friends Aleksandr Soprovsky, Bakhyt Kenzheev, Alexei Tsvetkov, and Aleksandr Kazintsev founded the group Moscow Time. Unlike Russian poetry groups of the early twentieth century, such as the Futurists or the Oberiuty, the Moscow Time poets did not issue manifestoes outlining the new aesthetic principles that united them. As Gandlevsky describes it, “We were friends, drinking buddies, we all were writing something and we would read it to each other, so sooner or later the idea arose of putting out little typewritten collections and declaring our literary community.” Rather than aesthetic principles, they were brought together by what Gandlevsky calls reasons of general worldview: “We were all idealists. We thought that death is not really the end. We did not think that there is no design and that the Universe is a confluence of some kind of molecular circumstances. We did not treat poetry as a simple variety of human activity—one person makes boots, another writes in rhyme.” As the original members died, emigrated, or gave up writing poetry, Gandlevsky joined other groupings such as the Almanac group and the club Poetry. The atmosphere of small groups working on their poetry with no hope of official publication is described in exhilarating terms in Trepanation of the Skull. In Illegible, a more satirical tone prevails, as Henseler notes. Through Krivorotov’s scornful eyes we see a motley collection of poets—students, schoolteachers, handymen—gathering in a dilapidated semi-basement meeting hall to read their works to each other. It all seems farcical and inconsequential until the day that Chigrashov, a poet of undisputed talent, with hard experience in the Gulag, appears to read his works, and the novel’s fatal course is set in motion.

Copyright 2019 by Susanne Fusso. All rights reserved.