Monica Rüthers is Full Professor of East European History at Hamburg University specializing in Eastern European Jewry, Soviet and socialist cities, Soviet/Russian childhood, and visual culture. Her book on the iconography of Soviet childhood, Born Under a Red Star (in German), appeared in 2020 from Böhlau Verlag Köln. She is also the author of an article on Soviet photo albums called "Picturing Soviet Childhood: Photo Albums of Pioneer Camps"

In the wake of Soviet collapse, Russian media were suddenly "free," people could travel abroad, and Western consumer goods appeared on store shelves. At the same time, Russia was a country in free fall. The state and new democracy were weak and hyperinflation twice killed the ruble, annihilating people’s savings in the process. The majority of the Russian population sank into poverty while a ruthless few rose to unimaginable wealth and power during the privatization of national property. Criminal structures proliferated. According to one version of events, Putin "saved" Russians from the chaos and humiliation of the "wild 90s." But there exists another, competing story: a story of freedom, told by contemporary youth photographs from the 1990s and now displayed in an internet picture flashmob.

In September 2015, the Russian online magazine Colta.ru asked its readers to participate in a virtual 1990s museum project, uploading their youthful portraits from the years following 1991. The response was overwhelming. In an article discussing the photographs readers submitted, the journalist Andrei Arkhangel’skii, born in 1974, presented a counter-narrative of the 1990s.

Arkhangel’skii contrasted the 1990s-era snapshots with Soviet photographs dating to the 1970s and 1980s, when parents took children to a studio photographer once a year. These portraits, Arkhagel’skii claims, were all alike “whether they were taken in Cherepovets, Batumi, or Kaliningrad.” The camera lens stood for a unifying “Soviet eye,” and the result, fixed on paper, was then sent out to aunts, uncles and grandparents.

The snapshots from the 1990s, by contrast, broke with every tradition. “People are displayed in moments of utmost deviation from the norm," Arkhangel'skii writes, their photos representing "acts of symbolic revenge for Soviet debasement and the order to ‘keep still!’” Gone is the rigid gaze into the camera lens, giving way to amazement at the new self. “Freedom as such was not yet understood; there was only bewilderment that, all of a sudden, everything was possible.” A new era of unexpected freedom unfurled before Arkhangel’skii’s very eyes, an epoch of dawning democracy and unlimited possibilities.

But a closer look at the pictures reveals still other things. Interspersed with the black-and-white prints are color photographs, with snapshots predominating over studio portraits. There are striking differences between portraits of children, who continued to be photographs by adults, and those of teens and young men and women, who took matters into their own hands. Since young people could now buy cheap disposable cameras and use services for developing and printing the photographs on their own, they were primed to try new things.

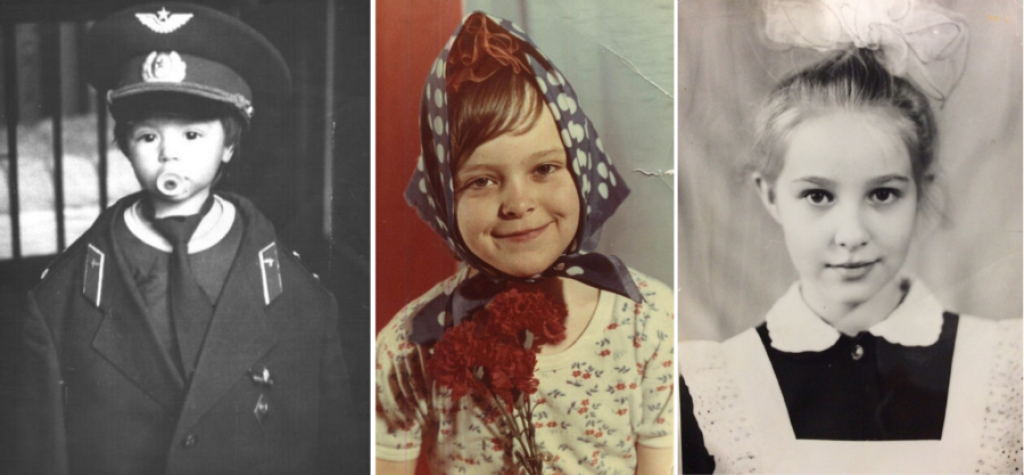

Children’s pictures were still taken by professional studio photographers and framed by Soviet traditions, fixed sets of conventions and narratives. They featured little girls in school uniforms with white aprons, huge hair ribbons, flowers and schoolbags, looking at the camera earnestly or with just a hint of a smile. A little girl wearing a headscarf seems to have stepped from the wrapper of an "Alionka" chocolate candy. A very small boy with a pacifier wearing his father's oversized uniform jacket and army hat takes up the well-known Soviet motif of the child-as-adult, the "relief."

Andrey, Olya, Tanya. Source: Nazad v 90-e. fleshmob na fishkakh

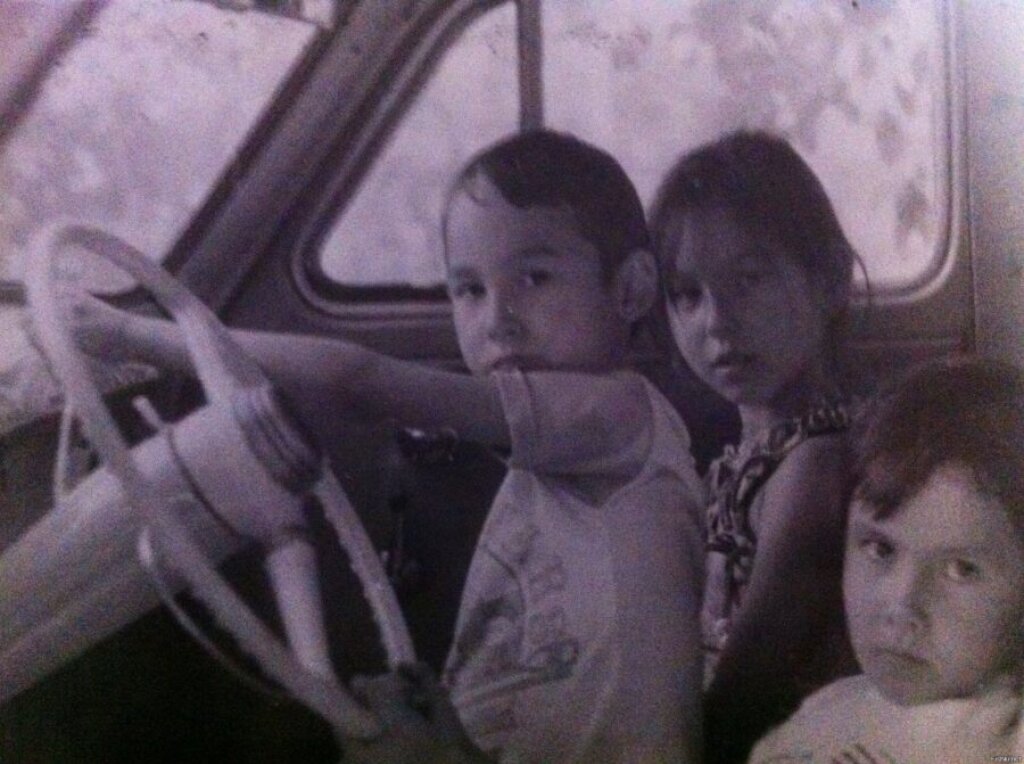

In family snapshots, children appear in front of the New Year’s tree or in the car; there are blurred photographs as well as carefully illuminated studio portraits, showing mother, father and child in silvery shades of grey.

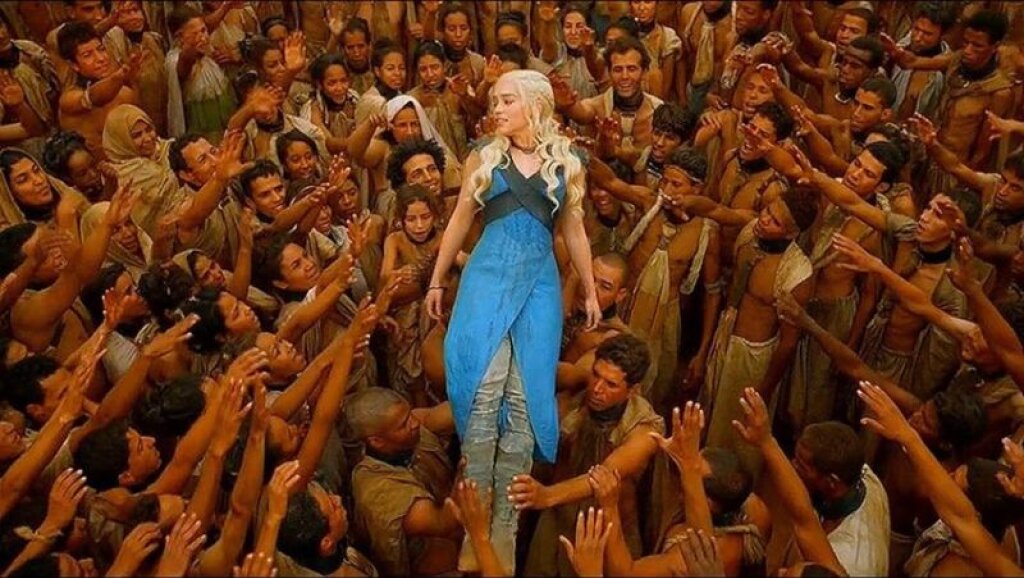

Source: Anton Chugrinov, Stikhiinyi fleshmob s fotografiyami iz 90-kh godov zakhvatil feisbuk, in: Snob.ru, 18.09.2015

Until well into the 1990s, children’s pictures were suffused with neither an atmosphere of disintegration and decay nor the breath of the dawning new era. Instead, they seem to have been part of parental strategies for coping with meteoric post-Soviet changes. These portraits suggest that parents took comfort in familiar visual practices, their children's sheltered aspect serving as a kind of imaginary panic room. These pictures fit into a set of widespread practices meant to fend off the dangers of impending hardship, like solving crossword puzzles or watching Latin American soaps, both of which attracted huge numbers of acolytes in 1990s-era Russia.

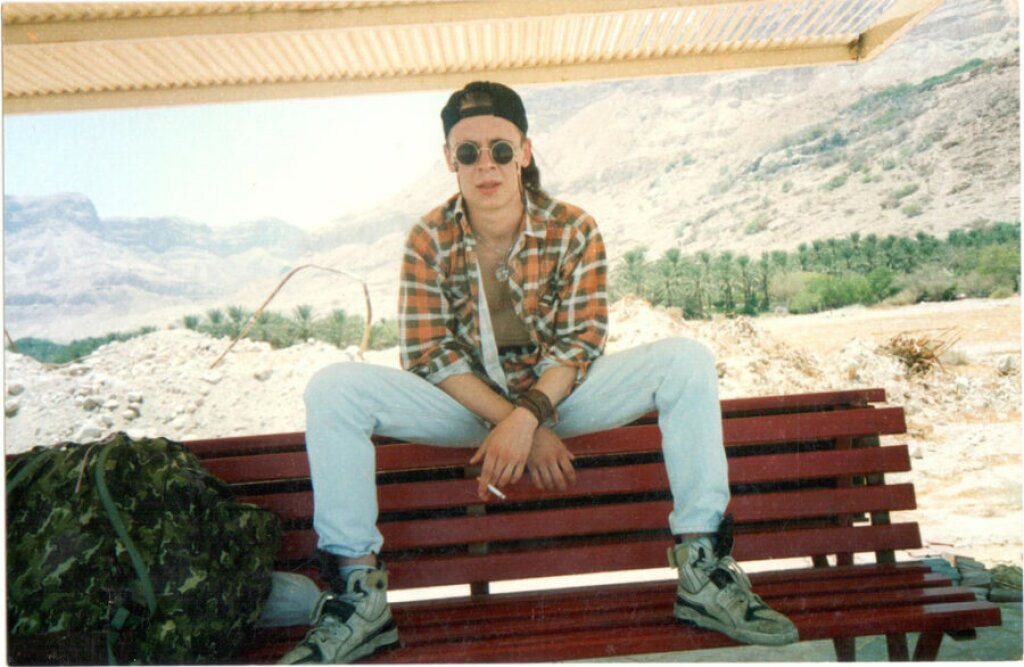

Pictures featuring teenagers and young adults, meanwhile, reveal how societal change inscribed itself not only in new ways of taking photos, but in the very bodies of those pictured — as when a teenager with an unbuttoned shirt and sunglasses slouches from his perch atop a public bench. In the Soviet Union, public behavior had been strictly regulated with strong norms governing clothing, hairstyles, and general attitude. Those deviating from these rules could expect public reprimands from their fellow citizens. But in the 1990s, this omnipresent social control of public spaces suddenly fell away.

The Russian convention of keeping one’s emotions in check is one of the reasons why, in “official” contexts like group or class photos, even children don’t smile. But the photographs of the 1990s have it all: blue hair, bared chests, dogs, eccentric poses, round sunglasses, and cigarettes dangling from mouths. Faces might be earnest or laughing; some people sit on the ground in public, while others hike in Russia's south or converse at parties. There is also evidence of the use of new technologies that, at the same time, inaugurate new conventions, such as a girl’s color self-portrait taken in a photo booth.

[gallery columns="2" size="full" ids="7412,7407"]

The photo flashmob of 2015 unveils a generational divide in the experience of the Russian 1990s. What for parents and grandparents seemed like a catastrophic loss, younger folks experienced as a chance to start a new life. In his article, now itself a historical artifact, Arkhangel’skii asks what became of this freedom after 15 years of Putin's rule. This question challenges the official narrative of collective trauma that attempts to flatten the diverse, tumultuous decade by calling it the "wild 90s" or the "decade of bandits."

In 2020, the online magazine Russia Beyond published an article by Ksenia Zubacheva interrogating this framing: “What was so ‘wild’ about 1990s Russia?” At the end of the article, Zubacheva quotes Ivan, a “businessman from Rostov,” who tells her that “when some say [the 1990s were] a time of freedom — I guess it was, but it was a bad kind of freedom, wild and bloody. I wouldn’t want to go back to it.”

Ivan may not want to go back to "freedom," but others do. New ways of sharing pictures on social media enable new perspectives — nowadays, people can discuss anyone's family photos during family gatherings, no just their own. Social media platforms enable the exchange of memories, including among large cohorts, which can look back together at their youth and their common dreams and expectations. And if the erstwhile youngsters of the 1990s start asking serious questions about what became of their youthful dreams of freedom, the consequences for Putin’s politics of "hyperstability" are difficult to foresee.