On November 1st, the Jordan Center hosted the event “Film Editing as Women’s Work: Esfir Shub, Elizaveta Svilova, and the Culture of Soviet Montage”, a talk by Professor Lilya Kaganovsky. Kaganovsky is Professor of Slavic, Comparative Literature, and Media & Cinema Studies, and the Director of the Program in Comparative & World Literature at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, and has published numerous works on Soviet and post-Soviet cinema. The talk, part of the Occasional Series, was introduced by PHD student of Comparative Literature at NYU Tatiana Efremova.

Professor Kaganovsky’s study focuses on the contributions of the two early Soviet female directors: Esfir Shub and Elizaveta Svilova, “in order to make visible what has largely remained invisible – film editing as women’s work”. According to Professor Kaganovsky, because of the Soviet gender politics and film industry specificity, these two women never assumed to be auteurs, and because their narratives did not conform to those of their male counterparts, their work vanished in the history of a male-dominated film industry. Kaganovsky also points to the fact that Western feminist film theory focuses on the absence of women and on the problematics of their representation, rather than on their behind-the-scenes contributions. The result is encapsulated in a quote by film scholar Jane Gaines: “They first fell out of limelight, and then out of history itself.” However, their contributions shouldn’t be downplayed, as it was Esfir Shub who invented the compilation documentary, and Elizaveta Svilova who made possible Dziga Vertov’s rapid montage. In her work, Kaganovsky attempts to disentangle the editorial and directorial contributions of both women from a male-dominated Soviet film industry, and add them to the discourse concerning the overall role of women in the propelling of both Soviet and global film history.

The two female editors in question hailed from very different backgrounds. Esfir Shub was born to a highly educated Jewish family in Ukraine, and was surrounded by artists and writers for the majority of her life. Along her trajectory she studied at several of the Soviet Union’s prestigious academic and artistic institutions, and met numerous influential artists, poets, and writers including Alexander Blok, Andrey Bely, Vladimir Mayakovsky, and eventually the filmmakers Sergei Eisenstein and Dziga Vertov, with whom she developed close professional and friendly relations. For a few years Shub supervised Eisenstein's montage workshop in Moscow’s VGIK film school, and later went on to become the chief editor of a culture and cinema journal. By the the end of her life, Shub directed over a dozen films and published a memoir, while her name continues to surface in many cinema history books

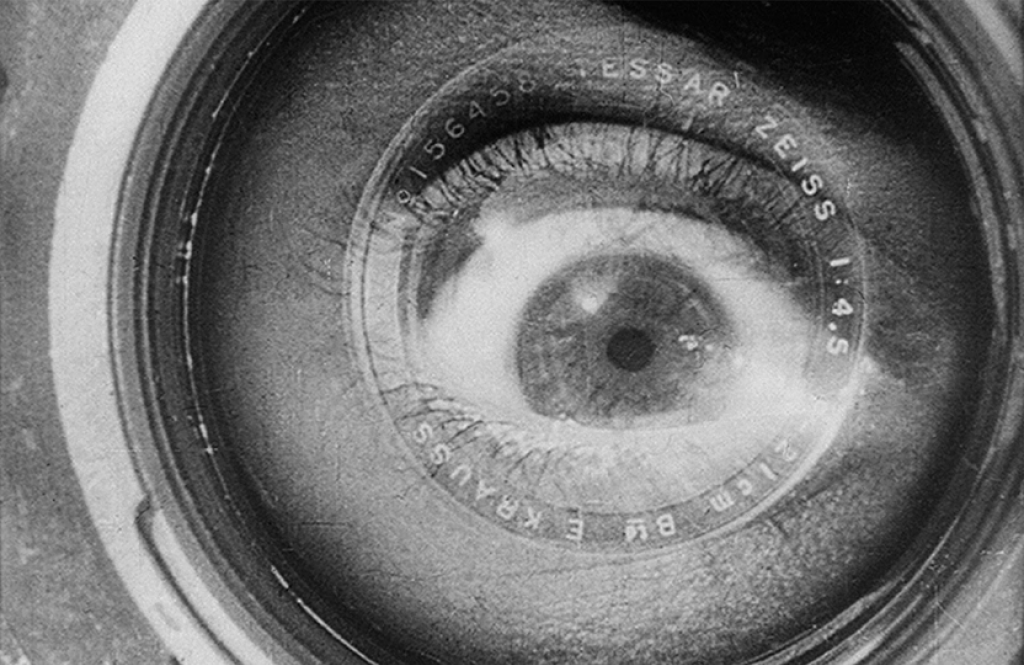

In contrast, Elizaveta Svilova remains almost entirely unknown. Born in the year 1900 to a working class family, she began apprenticing in the film industry at the age of 12. Much of her work encompassed the technical side of filmmaking: from using the cutter to printing the photos. In 1922 she began editing at the Goskino office, where she met Dziga Vertov. In 1929, after marrying the director, she played a major role in the production of Vertov’s famous documentary “Man With a Movie Camera”. Her lifetime body of work includes over 100 non-fiction films she directed, that range from newsreels to documentaries. After Dziga Vertov’s death, Svilova devoted her remaining years to archiving her husband’s work, whose name continues to overshadow her own.

Both women, according to Kaganovsky, began their careers as editors and eventually transitioned into directors. A close look at their contributions, Kaganovsky argued, can shift the focus away from the idea of the director as a male auteur. In the early history of cinema – both in the West and the Soviet Union, editing was always considered suitable for the female sex because of its similarities to sewing and other tedious handywork. The work was low-paying, and women were therefore considered perfect candidates. This element of invivisiblity, argued Kaganovsky, exists due to the ways in which “gender inequality relegated this line of work to secondary status”. Both Shub and Svilova were trained as editors, “designed from the first to be invisible”. Likewise, the idea that exposed footage was not considered “artistic”, until it is was arranged as a whole, contributed to the view that the director had the final word. In Svilova’s case, she was always credited as an assistant, who “made Vertov’s montage a reality without infringing on his artistic vision”.

Although Elizaveta Shub’s career mirrored those of her male counterparts, little is known about her due to a gender bias that stemmed from historical circumstances, argued Kaganovsky. Shub’s line of work “conformed to the avant-garde ideal of author as producer”, yet the industry continuously perceived her work as invisible. Her time spent behind the editing table helped her develop her intricate craft, but she strove to make the marks of her edits seamless – smooth replacements and transitions – and, essentially, “invisible”. Sergei Eisenstein actually learned montage from Shub, and Shub was regarded as the go-to person for any editing assistance among her “professional elite club”. After the release of her first compilation film “Fall of the Romanov Dynasty”, both Vladimir Mayakovsky and Eisenstein had to fight for her to be given her on-screen credit. Her work on the film – which was comprised of footage of the Romanovs and the revolution – wasn’t considered “directorial”, but was rather seen as splicing of existing footage. Yet, according to Kaganovsky, her “authorial invisibility made her very revolutionary”: her efforts in compiling, reframing, rescreening this footaged created a fluid narrative that told story of years leading up to revolution. Kaganovsky contrasted two photos to evoke Shub’s representation in the history cinema: one in which Eisenstein sits on the Romanov throne, embodying the “star of cinema”, and another in which Eisenstein and Shub are huddled together on a chair in the Winter Palace as two colleagues, equal in status, on a break from their work.

Elizaveta Svilova, who met Dziga Vertov in a state of despair and chose to help him “out of pity”, downplayed her contributions to her husband’s films in her own accounts. The cameraman Mikhail Kaufman, however, referred to Svilova as Vertov’s comrade-in-arms. Svilova wasn’t just responsible for organizing Vertov’s work into a final product, but was also, according to photographs, present at location shoots, hinting at the fact that her influence can also be traced to the directorial process as well. Svilova was often described wearing working class clothing, making her disappear “with ease” into the background. But an image of her and her husband hunched over pieces of film, creating, what Kaganovsky described as “something radically innovative while lacking all the basic resources,” speaks to an equal dynamic between the two, and a greater role played by Svilova. In his diary, Dziga Vertov himself expressed dissatisfaction with Svilova’s treatment as a second rate participant in the process.