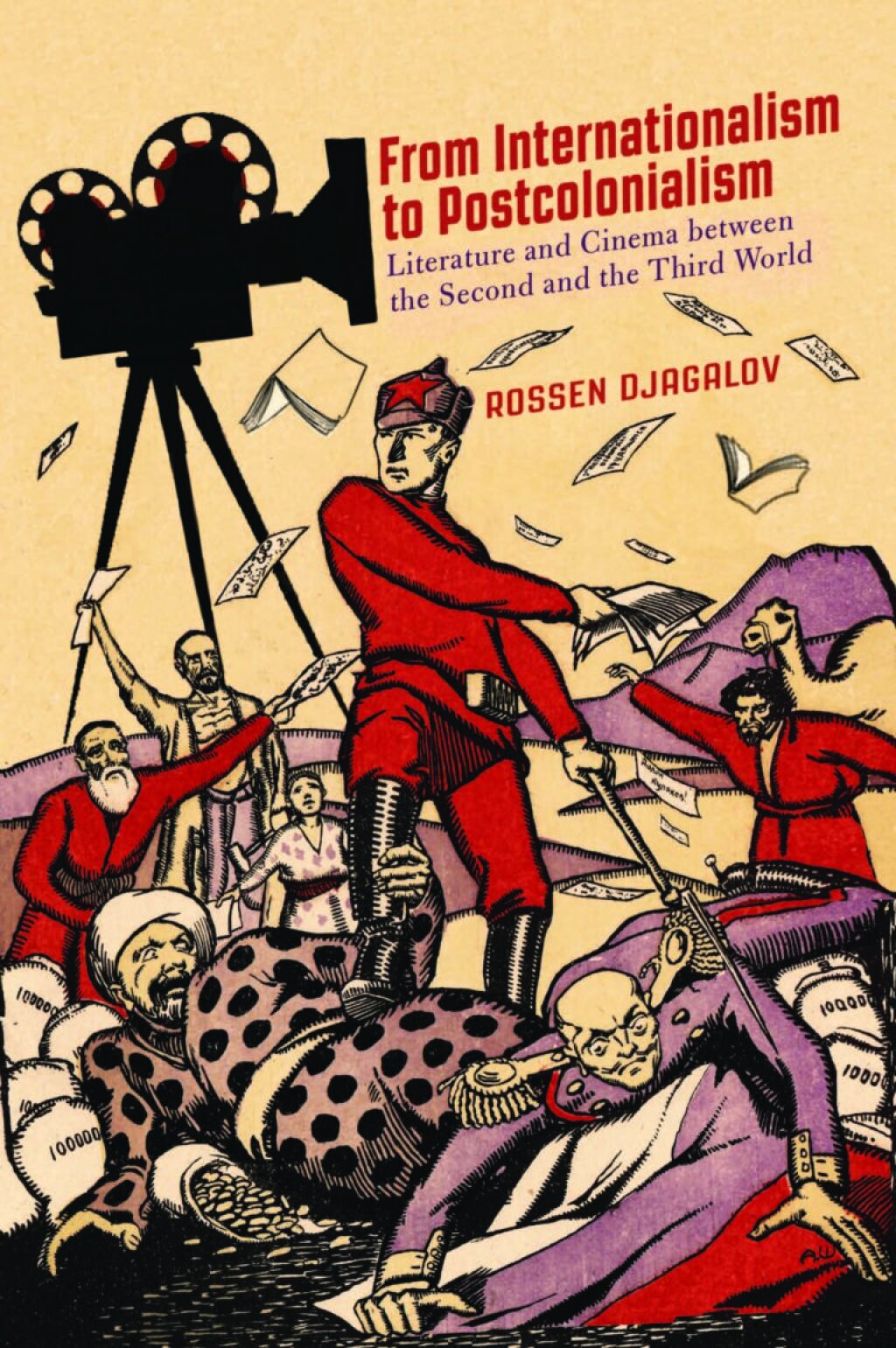

“Is the post- in postcolonial the post- in post-Soviet?” asked David C. Moore in 2001, prompting a reexamination of the dynamics between the Russian metropole and its Eurasian peripheries. But to deploy the postcolonial optic here is to presuppose the passing of an era of global ideological and cultural entanglements, primarily unfolding between the Second and the Third Worlds before the end of the Cold War. In his book talk on March 6th, 2020, Professor Rossen Djagalov revisited the history of Soviet Union’s cultural engagements with the literature, films, and cultures from a region now known as the Global South. His new monograph, From Internationalism to Postcolonialism: Literature and Cinema between the Second and Third World (McGill-Queens, 2020), reconstructs the Soviet Third-Worldist literary formation as that which bridges between the interwar-era internationalism and the present-day (post-Soviet) postcolonial studies. Rossen Djagalov is an Assistant Professor of Russian Slavic Studies at New York University, who focuses on socialist culture globally and, more specifically, on the linkages between cultural producers and audiences in the USSR and abroad. The talk was introduced by Yannis Kotsonis, Professor of History & Russian & Slavic Studies at New York University.

Professor Djagalov began the talk by revisiting the 1958 Afro-Asian Writers Conference in Tashkent, where several of the 200 attendees from Western and non-Western countries alike were meeting each other for the first time. Among them was W. E. B. Du Bois, who had just spoken with Nikita Khrushchev about the foundation of the the Institute for the Study of Africa in Moscow; the Turkish modernist poet Nazim Hikmet; the Pakistani Marxist poet Faiz Ahmad Faiz; the Chinese communist novelist Mao Dun and poet Guo Moruo; the Indian writers Mulk Raj Anand and Sajjad Zaheer; the Indonesian essayist Pramoedya Toer; the Senegalese novelist-cum-filmmaker Sembene Ousmane; the poet and founder of Angola’s Communist Party Mario Pinto de Andrade; and the Mozambican poet and FRELIMO politician Marcelino dos Santos. Also in attendance were some leading Russian, Central Asian, and Caucasian writers and Union of Soviet Writers officials, representing Russia, Dagestan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.

The conference marked the inaugural congress of what soon became known as the Afro-Asian Writers Association, a central platform for the Soviet cultural bureaucracies to encounter the literature of the two continents. Professor Djagalov contextualized the Association as one of the many Third-Worldist literary formations of the heterogeneous ideological engines at the time, an era of decolonization. Among them were the anti-communist Congress of Cultural Freedom, pan-Arab, pan-African, pan-Latin American cultural movements, and literary Maoism. Djagalov characterized the Afro-Asian Writers Association as the longest-lived (1958—1991), best sustained, and among the best resourced, despite its neglect for many decades since the fall of the USSR. Without fundamentally challenging the Western literary hegemony, the Association “left its own lasting impact in translations, literary circulations, and world-making,” Djagalov said.

But the encounter between Russo-Soviet and postcolonial literature had begun well before 1958. Djagalov compared the cultural capital of Tashkent to the Russian nineteenth-century literary tradition, both of which had come to epitomize the successful yet idiosyncratic modernization of Asian societies despite their late start (Chapter 1). To demonstrate the reception of Russian literature—as the literature of the people—among audiences in the East, Djagalov quoted Korean modernist writer Kim Myŏngsik, “While the literatures of the past [European literature] were all dead because they focused on poetics and emotions, Russian literature was alive because it brought social concerns to the literary realm.” As such, the early encounter with writers like Dostoevsky, Chekhov, and Turgenev had helped Asian intellectuals to contemplate the “elusive and yet all-important question of the people” in their own national contexts.

Cultural and literary entanglements continued to blossom after 1917, as Russian literature began to be read through the prism of the extraliterary, the October Revolution. Djagalov demonstrated how, throughout the interwar era, the Soviet Union sought to harness the “eclectic affinities” into actual engagements by spearheading different literary platforms that were then participated in by Asian, African, and Latin American writers. The International Union of Revolutionary Writers of the late 1920s and early 1930s, for example, held sessions in Japan, China, and Korea. Its successor, International Association of Writers For Defence of Culture, the Paris-based Popular Front organization, had attracted writers from South Asia and Latin America. Some of the constituent networks continued to operate independently later, even during Stalin’s Great Terror, which had paused most of the preexisting international cultural activities and dimmed the revolutionary zeal at home and abroad.

The Afro-Asian Writers Association then, along with two other geopolitical entities (The Literary World of the People’s Democracies, The European Association of Culture), represented the Soviet Union’s first attempt to return to the colonial question after Stalin’s death (Chapter 2). Though committed to NAM (Non-Alignment Movement) in the Cold War, the Afro-Asian Writers Association was heavily ‘aligned,’ argued Djagalov. “It served as a site for constituting international literary fields and deploying literature as a force for political engagement.” With a coordinating bureau in Sri Lanka, the literary quarterly Lotus, and an international literary prize, the Association had held subsequent conferences worldwide: in Cairo (1962), Beirut (1967), New Delhi (1970), Alma Ata (1973), Luanda (1979), Tashkent (1983), and Tunis (1988). The literary magazine Lotus was also multilingual, publishing contemporary prose, folklore, literary criticism, and book reviews by African and Asian writers between 1968 to 1991. “Much like Benedict Anderson’s [idea of the] newspaper,” Professor Djagalov wittily remarked, Lotus created “a sense of new and native single organism.”

The Afro-Asian Association and the greater internationalist cultural politics of the Soviet Union have left a tremendous, if underexplored, legacy for postcolonial studies today. “The Third World, as its name suggests, was predicated on the existence of the First and the Second, and with the disappearance of the latter [Second World], [it] has become categories devoid of political ambition,” said Djagalov. The post-Soviet collapse of the cultural infrastructure that had once interconnected the Third World—from Beirut to Cairo, from New Delhi to Havana—has subsequently led to the birth of the spirit of postcolonialism. As a present iteration of the Afro-Asian Writers Association, postcolonial studies continues the “inserting of the cultures of the three continents into the world canons,” not only through publication, scholarship, and syllabi, but also by critiquing the Western hegemony and introducing theories of new self-reflexivity. “What has changed, however, is not only the location of this cultural intellectual labor in its form but also in its substance,” stressed Djagalov, citing the replacement of the Third-Worldist militant aesthetics with politics of recognition and academic elitism. (Djagalov brought up the fact that the new discourse has struggled to circulate itself outside of the university campuses). The Soviet analysis of the ‘colonizer-colonized’ binary and the paradigm of progressive nationalisms have also succumbed to the poststructuralist celebration of hybridity and the study of diaspora and transnationality. The last and the major point of departure goes to the question of the state: once seen among Third-Worldists as capable of eliminating inequalities, facilitating industrialization, and promoting national cultures, the state has become at the very heart of the postcolonial critique.

In his conclusion, Professor Djagalov elaborated on some of the broader interventions his monograph has to offer, delving into other chapters in the rest of the book. They include the aesthetic consequences of the Soviet engagements in the realm of literature (Chapter 3) and cinema (Chapter 4 and 5). During the Q&A, questions were raised concerning Russia’s own hegemony and underlying epistemic violence in singlehandedly orchestrating a highly ideological Third-Worldist institution and aesthetic. Professor Djagalov agreed, problematizing Russia’s role as the ‘big brother’ in the supposedly egalitarian internationalist formation. “It is unfortunate that the Soviet state attempted to claim all these books [Russian or Afro-Asian literatures] as its representatives,” said Djagalov, adding that the Marxist tradition of anti-colonialism has been reflected in the Soviet politics with tremendous distortions in this respect. In the end, Djagalov nonetheless argued that it is possible to read Russian literature “regardless of ideologies,” hinting at the potential for local agencies and reinterpretations to emerge.