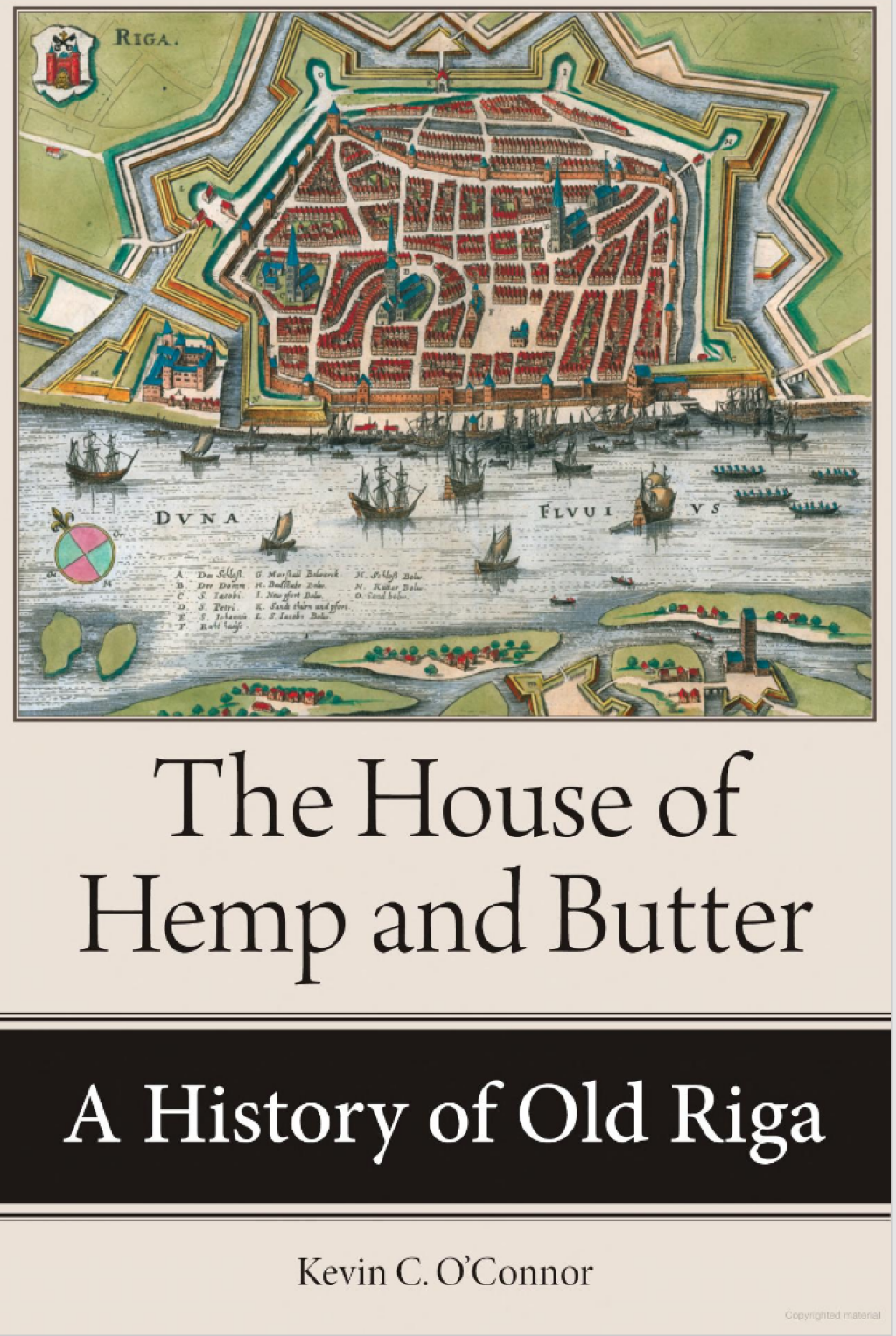

Kevin C. O'Connor is Professor of History at Gonzaga University. He is the author of a number of books, including The History of the Baltic States, Culture and Customs of the Baltic States, and Intellectuals and Apparatchiks.

This excerpt comes from The House of Hemp and Butter: A History of Old Riga, by Kevin C. O’Connor, a NIU Press book published by Cornell University Press. Copyright (c) 2019 by Cornell University. Included by permission of the publisher.

Riga is built on water. Largely obscured by modern development, the city’s aqueous environment is the legacy of an earlier geological age, when the global climate was far colder and harsher than today’s. As the first intrepid bands of homo sapiens began to spread their genes and their languages across the Eurasian landmass, the territory that presently comprises the city of Riga was still submerged in a blanket of ice several meters thick.

The enormous glacier covered a vast swath of northern Europe, from Scandinavia to what is now Berlin; but eventually the planet warmed and the ice began its slow retreat to the Baltic Sea. It was this process, beginning about 10,000 years ago, that resulted in the creation of those residual bodies of water that still cover some sixteen percent of Riga’s present-day territory. When the area’s first Stone Age human inhabitants arrived at the spot that would later give birth to a city, they would have found a sandy plain that was overlaid with veins of rivers and streams, bogs and marshes. Most of these waterways and wetlands have since vanished, buried beneath sand, dirt, and pavement so that Riga’s citizens would come to walk over the channels they would never see. Indeed, so much water flows under Riga today that the Soviet regime’s ambitious plan in the 1980s to build a metro under the city seems more fantastical than intrusive.

Riga’s relationship with the waters that run past, through, and under it has given rise to many legends and sayings. “In my eyes, Riga was long extolled,” goes one daina (a short Latvian folk song) about a peasant approaching the city; “now I see it: surrounded by sand hills, the city itself lies in water.” Everywhere there was water—water and sand. A mighty river, more than half a kilometer wide in some places, flowed past the city on its way to Baltic Sea. A moat dug by medieval Rigans provided an additional watery safeguard against invasion from the north, east, and south. And then there were the smaller channels that overlay the region’s sandy topography—including a minor tributary from which the city derived its name. Germans knew the rivulet that wound through the city as the Rigebach, the Riesing, or the Rising. Latvians called it by one of its diminutives, Rīdzene or Rīdziņa. History knows the lost channel as the Riga River, on whose right bank the city was founded at the dawn of the thirteenth century.

The etymology of this word continues to be debated. One theory is that the word “Riga,” or some form of it, was brought to the region by the Wends, a Slavic people who likely had been driven off the Baltic island of Rügen when the Danes conquered it in 1168. Or perhaps the name was derived from the Livish word ringa, meaning loop. “Riga” may also have originated from the local word for warehouse—rija—a place to store the goods that were being exchanged near the river’s banks. Whatever its origin, the name stuck: the word Riga would refer to both the rivulet and the settlement—later a city—around whose edges the ancient channel once flowed.

Meandering along the base of a sandy hill, the Riga River gently trickled past a Livish hamlet of farmers and craftsmen whereupon it widened into a small lake, ideal for docking the small sailing vessels that traversed the mighty Düna River that linked the forested interior to the Baltic Sea. It was along the Düna embankment that another Livish village emerged, less than a kilometer distant from its neighbor. A Finno-Ugric people who were related to the neighboring Estonians, the Livish peoples, or, if we go by their Latin name, the Livonians (Ger. Liven; Latv. Livi), were not alone in this unpromising environment: Cours and Wends lived nearby, and everyone lived in fear of raids by the Lithuanians. The flow of peoples through this region blessed the future city with one of its distinctive characteristics: Riga is, and has always been, a city shared by people of various nationalities and languages.

Riga’s founding was no secret at the time: it is mentioned in several medieval chronicles, and it is the subject of one, The Chronicle of Henry of Livonia, an indispensable account of the crusades that brought Christian missionaries and German knights to the northeast. The compilers of the partly-contemporaneous Chronicle of Novgorod, on the other hand, overlooked the new settlement. Among the best of the genre, this early Russian chronicle sketches the early history (1016-1471) of a great commercial city whose lands encroached upon those of the Estonian and Lettish (eastern Latvian) tribes. The chronicle reminds us that the Rus’, a Slavic-speaking people who were partly descended from a group of Viking (Varangian) conqueror-traders, were familiar with the area and its peoples.

Organized into a series of self-governing principalities headed by Kiev in the south and Novgorod in the north, the Kievan Rus’ (and their Varangian ancestors) had long been active in the eastern Baltic, bartering their goods with the locals who inhabited the lands along the great river that flows past Riga.

Indeed, the hamlet where the Livs bartered their wares was likely one of several stops the Vikings/Varangians made before they headed south along the river network that led to the Black Sea, where the Norsemen exchanged their goods for eastern treasures.

The Vikings’ flat and well-balanced longboats would eventually disappear, replaced by cogs from Germany and Scandinavia, whose high masts and large sails began to emerge from the spring fog with predictable regularity after 1158. Sometimes their passengers included men of the Catholic Church who wished to introduce the Livs and their neighbors to the Christian god. The western traders, however, were men of business, less concerned with souls and more with the profits to be earned from their exchanges with the local traders and especially with the Rus’ merchants who traveled from lands as distant as Polotsk, Smolensk, and Novgorod. Having concluded their transactions, the visitors then loaded their cogs with the bounty of the forested interior—fur and hides, beeswax and honey—for which they would return again the following spring.

It was on the shores of the Düna, on a field near the spot where the powerful river absorbed the trickle of the lazy Rigebach, that a young German bishop named Albert of Buxhoeveden (c. 1165-1229) established the city of Riga in 1201. And it was in and around this modest frontier town, transformed into a base for German traders and pioneers whose own settlements were juridically and physically merged with those of the older Livish villages, that the first sustained encounters took place between Latin Christendom and the pagans of Livonia.